1867: A SNAPSHOT OF THE MILITARY OCCUPATION OF NEW MEXICO

The 1867 U.S. Topo Bureau map showing the Old Territory and Military Department of New Mexico, “compiled in the Bureau of Topographic Engineers of the War Department chiefly for military purposes under the authority of the Secretary of War,” captures New Mexico in the midst of one of the most violent and unhappy periods of its history.

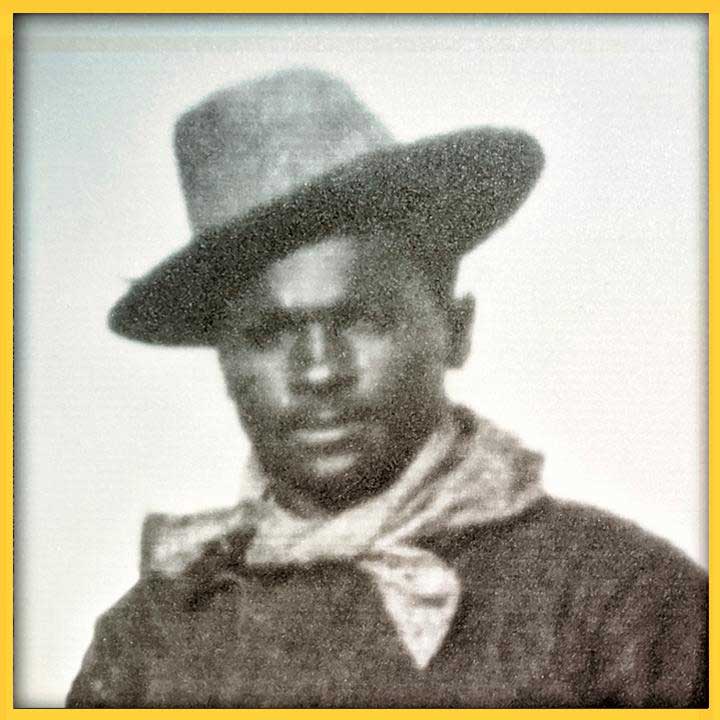

PHOTO CAPTION: Private Augustus Walley. Credit: National Museum of African American History and Culture, photographed by Ellen Dornan.

SHARE:

The 1867 U.S. Topo Bureau map showing the Old Territory and Military Department of New Mexico, “compiled in the Bureau of Topographic Engineers of the War Department chiefly for military purposes under the authority of the Secretary of War,” captures New Mexico in the midst of one of the most violent and unhappy periods of its history. Nearly twenty years into the military occupation, New Mexico is a network of forts, although some forts on this map were already in ruins (Fort Marcy) or never existed (Fort Butler). The military-fueled economy brought money and jobs to the state. The Old Spanish Trail, the shortest route to California’s gold fields, is marked on this map along with a paltry few other roads or trails, including the Santa Fe Trail leading back to Missouri, and a route to San Antonio pioneered by a Frenchman but rarely used for fear of the plains tribes.

The Civil War, surely still vivid to the engineers who made this map, had reshaped New Mexico’s borders. At the beginning of the war, Colorado was designated a state in order to preserve its valuable mineral resources for the Union. The new state absorbed New Mexico’s northernmost mountains and the traditionally New Mexican San Luis Valley. Arizona Territory was split off along the 109th meridian, despite the Confederate Territory of Arizona having claimed New Mexico south of the 34th parallel, from near modern-day Clovis all the way west to the Colorado River. The short-lived incursion of the Confederate Army may have felt triumphant as towns and forts fell before their onslaught, but ended with failure and defeat, thanks to Union Army reinforcements from Colorado.

As the war ended, the United States turned its energies into warring on the Native people, or as military documents put it, “securing the western frontiers.” Raids in New Mexico had increased while the Anglos fought each other, and the U.S. Army was willing to back an ambitious, but ill-conceived plan to remove some of the Natives from their homelands and turn them into peaceful farmers. In the years immediately before this map was made, the Diné had been driven from their homes, and forced to march to Hwéeldi, the place of suffering and fear, where they were held with many Mescalero Apaches. In 1868, the Diné negotiated a treaty enabling them to peaceably return to their sacred homeland. The full might of the military then turned against the Chiricahua, Mimbres and Mescalero Apache for another two decades.

Life was daily misery, privation, and danger for soldiers stationed out in New Mexico. James Bennett’s commander was killed by Apaches in the White Mountains, and although barefoot in February, Bennett survived the icy mountains on a “light diet” of horse and mule flesh and returned Captain Stanton’s remains to his widow. Malaria turned out to be a surprisingly bad problem for the riverside forts, and Fort Thorn was decommissioned eight years before this map was made because of epidemic conditions.

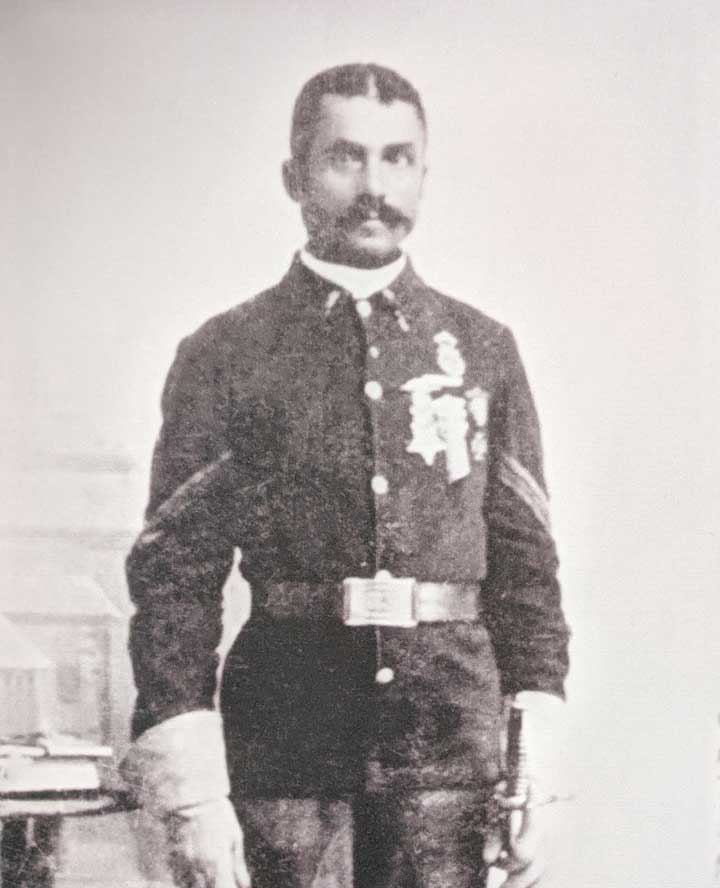

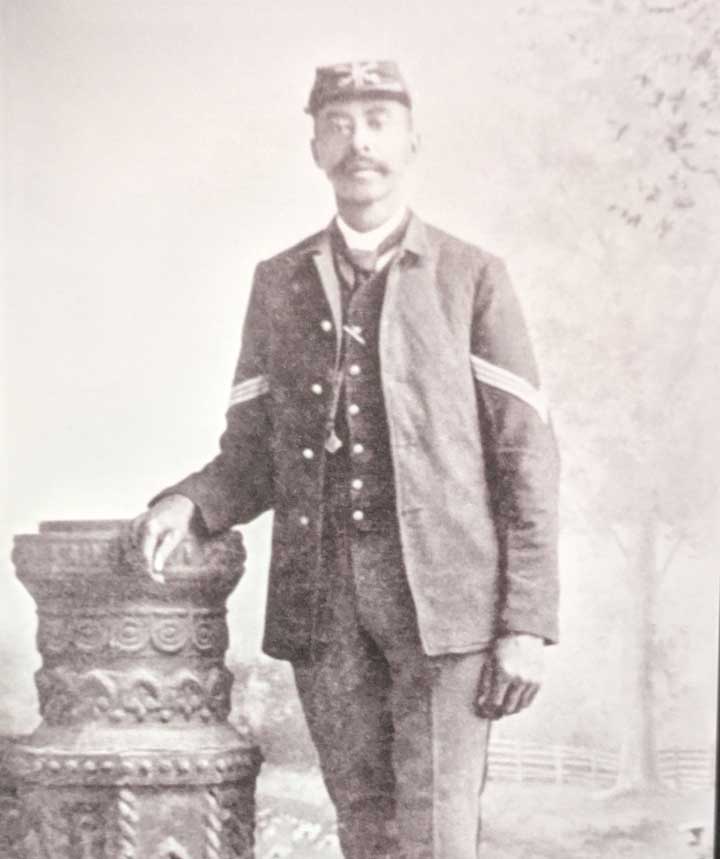

The military’s solution to the horrible conditions was to send in newly commissioned Black soldiers (later nicknamed Buffalo Soldiers), many newly freed and wishing to leave the south. The 57th and 125th Infantry Regiments arrived in 1866 and were stationed between Fort Stanton and Fort Selden.

Nothing about their service was easy, starting with the resentment of the white soldiers. The military doctor W. Thornton Parker recalls in his memoirs when the first detachment of Black soldiers was sent to Fort Craig for guard duty. The white soldiers there were “bordering on munity” and “bloodshed was seriously anticipated.” The white soldiers refused to present arms or acknowledge the new guard despite direct orders, so the officers hung them by their thumbs until they agreed to “salute the uniform of the United States” regardless of who was wearing it.

The Black infantrymen often got the most menial or dangerous jobs. Most jobs at some forts, like gathering firewood, were both. Fear of encountering the Apaches was constant, so soldiers could not leave their garrison without permission, and usually hunted in large parties.

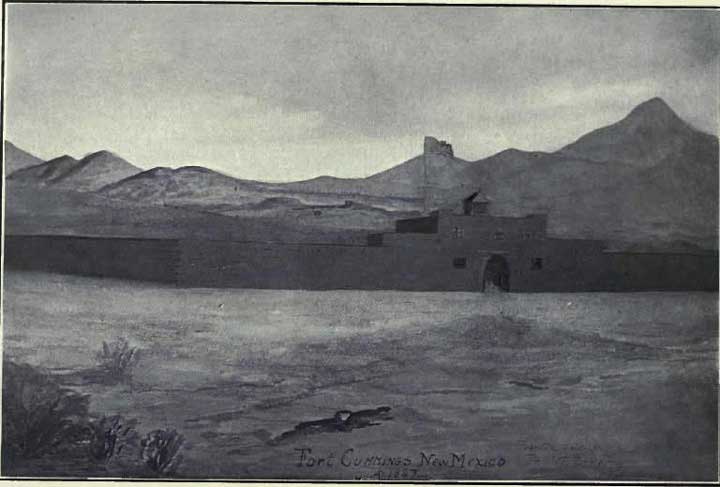

Describing the troops’ life at Fort Cummings in 1867, Parker wrote “to the west and southwest stretched the limitless prairie, dreary and desolated. The only green things visible in the landscape were the few stunted trees at the spring, half way between the Fort and the entrance to Cook’s Cañon. After marching for days and weeks through an enemy’s country, with the rough mess-kit of a campaigner, with the horror of a visitation of cholera, to which their brave surgeon and his wife fell victims, these ignorant colored soldiers, who had been buoyed with delusive hopes on leaving the fertile fields of Georgia, found themselves in this dreary, prison-like abode, exposed to all the discomforts of a home in the desert, and to all the dangers of a powerful tribe of merciless Apaches, forever on the warpath.” On top of that, “Every possible punishment employed in the discipline of frontier posts was inflicted on them.”

Despite the hardships of these posts, and the discouraging beginnings, the Black troops distinguished themselves as “trustworthy, brave and intelligent,” particularly the 24th and 25th Infantry and the 9th and 10th Cavalry. The fabled 9th Cavalry relocated their regimental headquarters to Fort Union between 1875-1881, and from there deployed to Fort Bayard, Fort Craig, Fort Cummings, Fort McRae, Fort Selden, Fort Stanton, Fort Tularosa and Fort Wingate. The 9th Cavalry not only fought bravely against the Apaches in “Victorio’s War,” but helped restore peace during the violent upheavals in Lincoln and Colfax counties.

Geronimo’s band of Chiricahua Apache surrendered in 1886, and the United States slowly decommissioned their forts, allowing some to crumble into the ground, and repurposing others as hospitals. The final active Black regiments, members of the 25th Infantry Regiment and ninth Cavalry Regiment, were stationed at Fort Bayard and Fort Wingate 1898-1899. After leaving the military, many men established homesteads, particularly in eastern and southern New Mexico.

Dr. Paul Hutton, distinguished professor at UNM’s History Department, commented on the role these newly freed men played in bringing peace to the territory and paving the way for statehood. “With the hindsight of history, what an important part they were. Not only in the development of the west but in moving forward with African American rights, because by fighting for their country, by dying for their country they proved that their blood was as red as any other American blood and so they really paved the way for the fully integrated military that we have today, and they did so in the face of intense racism.”

People wishing to explore the history of the Buffalo Soldiers or the territorial military can learn more by visiting state historic sites at Fort Stanton, Fort Selden and Fort Sumner/ Bosque Redondo; or federally managed Fort Craig Historic Site; Fort Union National Monument, and Fort Bayard National Cemetery.

NMHC’s online Atlas features historic New Mexico maps, annotated with the words of people who were in those places at that time, as well as historic images, oral histories, and bibliographic links to full text books. Register for a user account to save and share info windows and map views.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

A DIFFERENCE-MAKING BOOK

By Richard Etulain

“Many authors hope their histories, novels or other writings will make a difference — that their works will catch readers’ attention and influence their thinking and actions.”

CELEBRATE CONSTITUTION AND CITIZENSHIP DAY EVERY DAY, NOT JUST SEPT. 17TH

By Maryam Ahranjani

“As a teacher and mother and child of immigrants who now teaches Constitutional Rights to law students, this day is always a special one for me.”

THE THIRTEENTH AMENDMENT THAT NEVER WAS

By Brandon Johnson

The 13th Amendment, guaranteeing the abolition of chattel slavery in the United States, is one of the crown jewels of the American Constitution.

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

ELLEN DORNAN

Ellen Dornan serves as the CIO and the Digital Humanities Program Officer. Ms. Dornan has worked with the Council since 2001, serving as webmaster, NHD judge and junior division coach, and a scholar on grant projects and the Centennial Online Atlas of Historic New Mexico Maps. She joined as full-time staff in January 2016.