SHARE:

Billy the Kid is the most-written-about New Mexican. Most of the nearly 1,000 books and essays about Señor Billy picture him as a villain, hero, or combination of the two.

But is there another kind of Billy the Kid? Is there a more human young man — one beyond the drama and even sensationalism of the usual Billy? There is. A second Billy emerges from familiar sources.

First of all, Billy was family-challenged. No one has located for certain Billy’s biological father. His mother Catherine McCarty, however, served as a helpful, encouraging, and interested parent. In Silver City, where Billy lived from 1873 to 1875, friends of his thoroughly saluted Catherine. She was, according to Louis Abraham, “a jolly Irish lady, full of life.” In all ways, Catherine was a supportive, loving mother. So, when she died from tuberculosis in 1874, Billy lost his best friend.

Unfortunately, Billy’s stepfather William Antrim, whom Catherine had married in 1873, proved to be an inattentive father. Searching for his own mineral stake, Antrim essentially abandoned Billy and his brother Josie. Now Billy had no real parent on scene.

Without parents, Billy began to wander — and regrettably, into the hands of George Schaefer (“Sombrero Jack”). A drunk and thief, Schaefer led Billy into thievery. Here was an emerging pattern in Billy’s life — without parents he con

John Mackie (McAckey) who led Billy into horse-stealing.

A tragic second pattern of Billy’s personality also surfaced in Arizona: He too often acted without thinking. When bully Windy Cahill began to pummel Billy in a hurtful wrestling incident, Billy pulled his gun and shot — and killed — Windy.

Fleeing Arizona and moving to eastern New Mexico, Billy again looked for a big brother-father figure. Fortun

A third facet of Billy’s character quickly surfaced. He needed to be with a group. He found one with the Regulators who set out to gain revenge on Tunstall’s murderers. Within

After several shootings— including a “Big Kill” — took place in the Lincoln County area, and several leaders of the Regulator “chiefs” lost their lives, Billy became a leader of outlaws. During the last years of his life —roughly 1879 to 1881 — Billy led thieves in stealing horses in New Mexico and selling them in Texas, or, in reverse, stealing horses in Texas and selling them in New Mexico.

Here, a final facet of Billy’s personality became evident. Even though still a teenager and less than 21, Billy was able to gather other men around him to satisfy his desire to be with others. For the most part, men who rode with Billy — and many others, too — pictured Billy as a man they liked. To quote a familiar southwestern description, “He was a man to ride the river with.”

So, here is a Billy different from the more stereotyped villain or hero appearing in most books or essays about the Kid. The loss of his parents by his mid-teens probably did most to lead him down a path of bad decisions. Second, he frequently acted without thinking through the consequences. Third, he needed company and, over time, moved from follower to leader in New Mexican groups and attracted attention throughout the Southwest. That was Billy the Kid, from the more human side.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

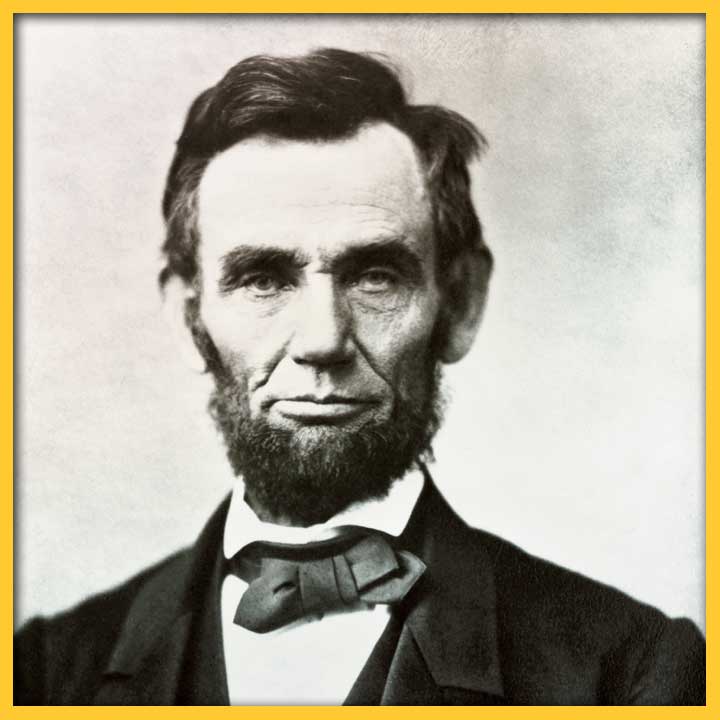

THE THIRTEENTH AMENDMENT THAT NEVER WAS

By Brandon Johnson

The 13th Amendment, guaranteeing the abolition of chattel slavery in the United States, is one of the crown jewels of the American Constitution.

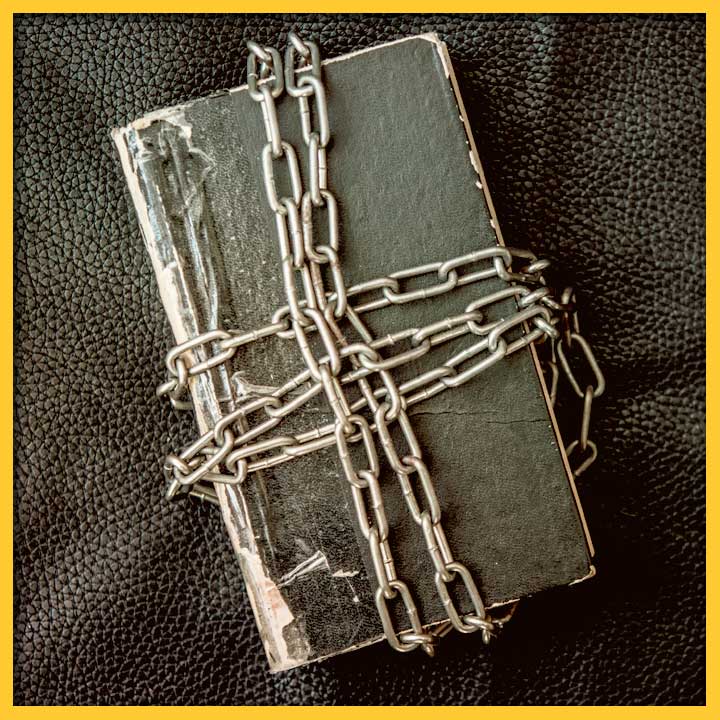

LIBRARIES AS FOUNDATIONS OF DEMOCRACY: UPHOLDING THE FREEDOM TO LEARN

By Val Nye

Proponents of intellectual freedom and supporters of libraries should plan to join in the various celebrations happening in New Mexico to honor the work communities and library workers do to retain intellectual freedom rights for all Americans.

SPAIN AND THE U.S. WAR OF INDEPENDENCE

By Eloy García

As we approach the U.S. Semiquincentennial of July 4, 2026 I think it is important that we in New Mexico reflect on the influence the Spanish Empire had on ensuring the success of the British colonist “War of Independence.”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

RICHARD ETULAIN

Richard W. Etulain is professor emeritus of history at the University of New Mexico, where he taught from 1979 to 2001. He served as editor of the NEW MEXICO HISTORICAL REVIEW and director of the Center of the American West (now the Center for the Southwest). He is the author or editor of more than 60 books. He was elected president of both the Western Literature and Western Historical associations.