BELOVED WORD WARRIOR: THE POWER OF TONI MORRISON'S PEN

In celebrating Women’s History Month, we acknowledge Toni Morrison’s indelible legacy, where her identity as a woman and an African American is inseparable from her literary genius.

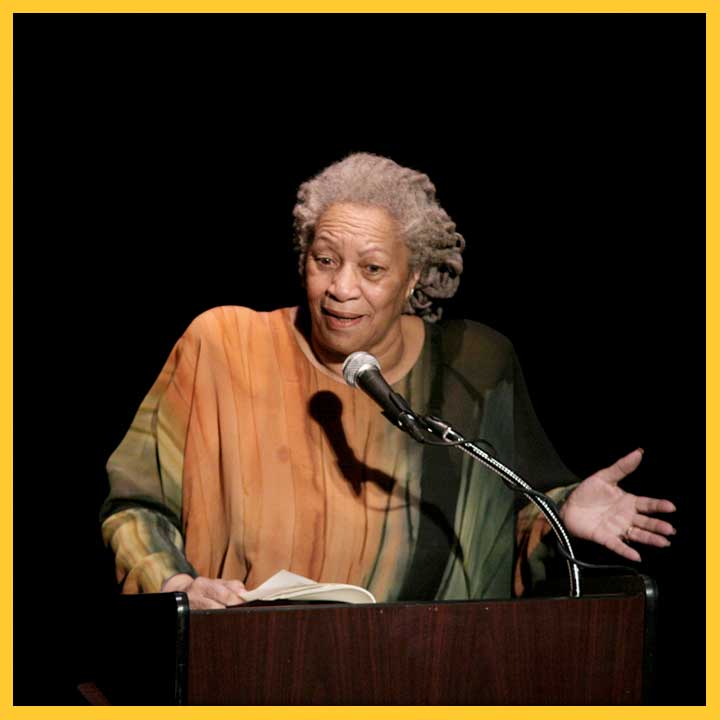

PHOTO CAPTION: Toni Morrison speaking at “A Tribute to Chinua Achebe – 50 Years Anniversary of ‘Things Fall Apart'”. The Town Hall, New York City, February 26th 2008. Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

SHARE:

Fighting battles for control has been a constant in our society. In this world where violence, both past and present, continues to fracture our societies, Toni Morrison’s pen emerges not just as a tool of creation but as a weapon of profound transformation.

It’s Women’s History Month, and, truthfully, it always feels a bit odd to define people by their gender or race. Still, I’m honored to be able to highlight the accomplishments of and bring awareness to the contributions of people who look like me, who have demonstrated the courage to speak truth about justice and the need for America to live up to the true meaning of its creed — liberty and justice for all.

This tribute explores how Morrison modeled using her writing to combat the silence surrounding the Black/African American experience and women’s narratives. In celebrating Women’s History Month, we acknowledge Toni Morrison’s indelible legacy, where her identity as a woman and an African American is inseparable from her literary genius.

Far from diminishing her prowess, these facets of her being, in fact, magnify the significance of her contributions. Morrison’s narratives weave the textures of her lived experience and heritage into a profound exploration of humanity, challenging societal norms and enriching our understanding of identity and resilience. Her work transcends mere storytelling; offering a lens through which the struggles and triumphs of women, especially Black women, are acknowledged and celebrated.

Morrison’s legacy, rooted in her unique perspective, is a testament to the transformative power of writing with authenticity. Her life and literary contributions are a replicable playbook for resistance, resilience and elevating voices marginalized by systemic oppression. Morrison chose the proactive path of enlightenment and empathy over the destructive forces of hatred and division, illustrating the enduring power of words to heal, empower and enact change.

Born Chloe Ardelia Wofford in 1931 in Lorain, Ohio, Toni Morrison grew up in a family that taught her to love African-American folktales and the oral traditions of the South. Paying homage to the West African tradition of the griot and storytelling, her family passed down stories about ghosts, the supernatural, and the everyday experiences of the people in the village. These narratives and a deep reverence for history profoundly shaped her educational experience and her literary voice.

She pursued an English degree at Howard University and later a master’s at Cornell. Upon finishing her studies, she deepened her love for words and history when she taught at two historically Black colleges and universities (HBCU’s) — Texas Southern in Houston and her alma mater Howard University in Washington, D.C.

In 1965, she landed a job at Random House, marking the beginning of a significant phase in her career that would intertwine her editorial work with her development as a novelist. Morrison was initially hired as an editor for their textbook division in Syracuse, N.Y. Later, she moved to New York City when she became the first African American woman senior editor in the fiction department at Random House’s headquarters.

While at Random House, Morrison played a pivotal role in bringing Black literature to the forefront, championing authors such as Angela Davis, Gayl Jones and Muhammad Ali, among others. Her tenure at Random House was not just a job; it was a mission to ensure that women and Black voices and stories were heard, respected, and given the platform they deserved. It should be noted that she did all of this while raising two young children as a single mother. Her marriage ended in divorce near the beginning of her career at Random House.

“If there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.” — Morrison’s 1981 Speech to the Ohio Arts Council

While she was committed to elevating the voices of women and Black writers, there were books that she wanted to read that had not yet been written. She often spoke of this commitment to read stories that resonated with her experience as a Black woman, unfiltered by the gaze of the white majority. This approach not only won her legions of readers but also placed her at the forefront of literary discourse.

Her work touched me and my household in a profound way. My own mother, Rubye Carter, was the first Black English teacher at an all-white high school in Muskogee, Oklahoma, and she proudly introduced Toni Morrison’s debut novel The Bluest Eye (1970) to her classroom.

I recall the controversy she encountered when she introduced this novel that explored race, identity and standards of beauty in her pseudo-south Oklahoma classroom. I’m not sure if she knew of the numerous rejections Morrison experienced before the book was published, but her resolve for the book to be included was resolute. The book itself wasn’t a financial success but it achieved critical acclaim, and I, and many other Black women like me, have had a copy of the book on our shelves for decades.

The Bluest Eye set the tone for Sula (1973), her second novel that explored the intricacies of female friendships in Black communities. Morrison’s third novel, Song of Solomon (1977), a rich tapestry of African-American heritage and folklore, earned her the National Book Critics Circle Award.

Beloved (1987), perhaps her most famous work, based on the true story of a runaway enslaved person, won the Pulitzer Prize and solidified her stature in American literature. This novel, alongside Jazz (1992) and Paradise (1997), formed a trilogy that depicted different aspects of Black life in America. Morrison’s later works, including Love (2003), A Mercy (2008), and God Help the Child (2015), continued to explore themes of love, trauma and resilience in the African-American community.

This woman, Chloe Ardelia Wofford – Toni Morrison, is now an ancestor. She left us on Aug. 5, 2019. And while she received critical acclaim, including the 1993 Nobel Peace Prize for Literature, I believe, and I think she would agree that her most significant accomplishments were in her contributions to amplifying voices that had been marginalized. She helped to free us with the power of her words and she encouraged us to follow in her footsteps when she said, “The function of freedom is to free someone else.” And so it is.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

SPACESHIPS, RAY GUNS, AND LIFE LESSONS

By Melinda Snodgrass

“science fiction allows you to discuss difficult and fraught topics in what is a safe space and at arm’s length.”

LITERATURE AS GUIDEPOSTS ON MY IMMIGRANT JOURNEY

By Kei Tsuzuki

“What I have learned from books is that there is no one story that explains the world to us or captures our identity entirely. There is power in the specificity of each of our stories…”

A DIFFERENCE-MAKING BOOK

By Richard Etulain

“Many authors hope their histories, novels or other writings will make a difference — that their works will catch readers’ attention and influence their thinking and actions.”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

CATHRYN MCGILL

Cathryn McGill is the Founder/Director of the New Mexico Black Leadership Council. McGill is committed to being a part of creating a New Mexico where "Everyone Belongs". In the West African tradition, she is a Griot - a musician, a storyteller and a unifier.