BEYOND THE MACABRE: EDGAR ALLAN POE AND THE PSYCHOLOGY OF HORROR

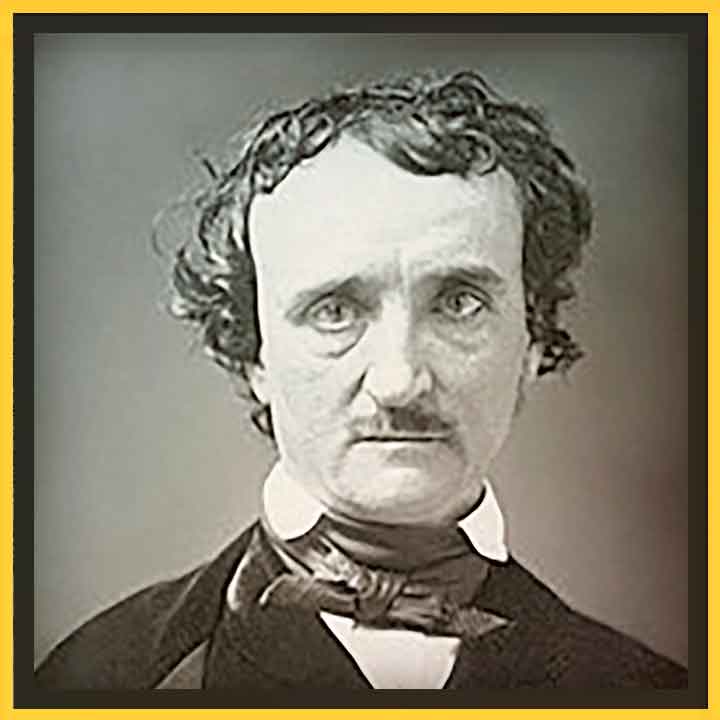

Edgar Allan Poe’s status as the father of contemporary horror is so fully entrenched in the American psyche that his portrait is instantly recognizable to people who have never read his work.

PHOTO CAPTION: “Annie” daguerreotype of Poe circa 1849. Credit: Unknown author; Public Domain; originally from here.

SHARE:

Few writers achieve the kind of longstanding notoriety that inspires comics, historical fictions, and feature films. Edgar Allan Poe’s status as the father of contemporary horror is so fully entrenched in the American psyche that his portrait is instantly recognizable to people who have never read his work. The fascination with Poe, not just with his stories but as a uniquely grim, American story of his own, came to its bizarre apex in the 2012 film The Raven, with John Cusack as a morbidly charismatic Edgar Allan Poe on the hunt for a serial killer. Exceptionally few authors from any time, but especially from the nineteenth century, have their work converted to film—and even fewer become the stuff of fiction themselves. Born in 1809 and orphaned at the age of three, Poe lived a turbulent and often tragic life before eventually dying under mysterious circumstances in 1849, producing a body of work that evinces a sense intimate and unrelenting psychological anguish. The American literary cannon has undergone radical, and in many ways desperately overdue, changes in the last 200 years. Despite this shifting literary landscape, Edgar Allan Poe’s haunting legacy continues to appeal to American readers and non-readers alike, and with good reason.

While Poe’s name usually conjures images of the macabre and the supernatural, the power of his writing is rooted in his determination to fully explore, and sometimes fully inhabit, the human experience—even or especially in its extremities. “The Raven,” one of the most famous poems ever written in the English language, takes readers into the mind and misery of a man whose lover has died and who fully descends into madness by the end of the poem. The text’s eponymous raven perches overhead, repeating “Nevermore” as grief drives the narrator deeper and deeper into despair. Although the poem is structured in a way that draws attention to the raven’s speech, Poe never fully clarifies if this is the product of the supernatural or insanity. In doing so, Poe positions the reader on the cusp of madness, and never provides a resolution. Reading “The Raven,” we follow Poe and his narrator not just into the depths of human suffering, but into an uncanny space where we cannot trust our own sense of what is real and unreal. Our distrust of the narrator’s sanity is experienced alongside the unsettling sensation that we may not be able to disentangle the sane and the insane within the world of the poem. We never know, truly, if the raven speaks. Ultimately, it isn’t the raven’s speaking that elicits our fear, but the pressing certainty that neither the reader, nor the narrator, is capable of distinguishing between reality and madness.

In “The Tell-Tale Heart,” Poe takes his readers a step further, firmly placing them in the mind and heart of a killer who begins his tale with a declaration of sanity. The fact that he has committed a murder, dismembered the victim, and hidden the body parts beneath his floorboards is less concerning than the possibility that, somewhere along the way, he may have lost his mind. By the end of the poem, we realize the sound of his victim’s beating heart beneath the floorboards is merely a hallucination, but it is too late. We have already experienced the murder, the guilt, and the dread of being exposed through the eyes of the killer. Poe takes us somewhere we would never go willingly—into a place of identification with a murderer. Despite the gruesome details of the homicide and subsequent dismemberment, the true horror of the story takes place between the reader and the narrator, with the reader struggling to navigate a doomed sense of empathy for a killer. Poe leads us into a head-on collision with the complications of our own moral compass and our desire to read, and experience, life by relating to others.

While Poe’s name calls to mind visions of the supernatural and macabre, the real force of his writing, the heart beating under the floorboards, lies in his commitment to exploring the gray zones of human experience. Hopefully, only a few of his readers have truly experienced the descent into madness after the loss of a loved one, or the looming sense of dread after committing an unspeakable crime. But we have all questioned our sanity. We have all felt the pangs of paranoia. We have all watched in dread as the consequences of our own actions loomed, ghostlike, on the horizon. Poe’s mastery, the reason generation after generation of readers return to his work, is his ability to lure us into a confrontation with the complex reality of our own human frailty. The terror we feel in the grasp of his writing is the terror we refuse to see in the mirror.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

LITERATURE AS GUIDEPOSTS ON MY IMMIGRANT JOURNEY

By Kei Tsuzuki

“What I have learned from books is that there is no one story that explains the world to us or captures our identity entirely. There is power in the specificity of each of our stories…”

A DIFFERENCE-MAKING BOOK

By Richard Etulain

“Many authors hope their histories, novels or other writings will make a difference — that their works will catch readers’ attention and influence their thinking and actions.”

CELEBRATE CONSTITUTION AND CITIZENSHIP DAY EVERY DAY, NOT JUST SEPT. 17TH

By Maryam Ahranjani

“As a teacher and mother and child of immigrants who now teaches Constitutional Rights to law students, this day is always a special one for me.”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

CHRYSTA WILSON

Chrysta Wilson is a doctoral candidate specializing in Multi-Ethnic American Literature at the University of New Mexico. Her research focuses on dehumanization and the intersections of race, gender, and sexuality. Drawing on work by US writers of color in the nineteenth and twentieth century, she is particularly interested in embodiment and identity. Her current projects interrogate complex and sometimes ambiguous visions of masculine embodiment in Chicano literature, particularly in relationship to stories of origin and questions of citizenship.