BREAD OF DEATH AND LIFE: A SHORT HISTORY OF PAN DE MUERTOS

‘Bread is life.’ This platitude is among the most well-known in our culture, yet when we consider the Mexican holiday El Día de los Muertos and the food associated with that celebration, it takes on a much more significant and poignant meaning.

IMAGE: Bread for the departed on family altar, photograph by Vanessa Baca

SHARE:

For me, it’s not truly El Día de los Muertos until I read the following quote by the Mexican author Octavio Paz from his masterpiece El Laberinto de la Soledad: “Para el habitante de Nueva York, París o Londres, la muerte es palabra que jamás se pronuncia porque quema los labios. El mexicano, en cambio, la frecuenta, la burla, la acaricia, duerme con ella, la festeja, es uno de sus juguetes favoritos y su amor más permanente.”

Paz personifies how death is perceived within his own culture. His fellow Mexicans play with death, dance with death, make jokes about death, sleep with death, celebrate death, and love it beyond all else. Death, after all, is something that comes for each of us, and it is this concept of death being one of the strongest connectors between cultures that creates a strong sense of unity among disparate individuals and societies. We are all going to die at some point. And in order to keep living, we must all partake of food.

“Bread is life.” This platitude is among the most well-known in our culture, yet when we consider the Mexican holiday El Día de los Muertos and the food associated with that celebration, it takes on a much more significant and poignant meaning. Food is another interlacing between cultures, societies and ethnicities, and remains so even in death. Pan de muerto, the famous bread of the dead, is ubiquitous to El Día de los Muertos, with its orange-anise perfume and sugary crunch being as much a part of the holiday as the traditional altars laid with candles, marigolds, photographs, and food and drink.

Food plays a significant role in conjunction with death the world over. Funerals in all countries commemorate the life of the deceased by gatherings, music, pictures and always some type of repast meant to sustain the living, as well as to honor those who have gone on; and can be considered a means of both remembering the deceased and of keeping them included in community. Though El Día de los Muertos is arguably more familiar to Americans, ancient and modern cultures as diverse as Celtic, Egyptian, Jewish, Japanese, Northern Italian, Moroccan and South African, to name just a few, all have their own unique ceremonies and rituals that offer comfort to the living, create a sense of remembrance for the dead and incorporate food.

In Mexico, and by extension the United States, El Día de los Muertos is celebrated on November 1 and 2, in the immediate aftermath of Halloween, which itself is an evolution of the ancient Celtic commemoration of Samhain, or as it is more commonly known in modern times, the autumnal equinox. The ofrendas – altars – created in honor of the dead are alight with candles, fragrant with flowers and filled with plates of favorite food of the deceased, as a means of enticing them to return from the land of shadow. It is believed that the light of the candles, the photographs, and the scents of flowers and food create a beacon by which our dead return to us, partake of the celebrations in their honor and enjoy the bounty of food that is left for them, and one of the beloved foods associated with the holiday is pan de muerto.

Pan de muerto has no certain genesis. Some historians believe it originates as a type of sweet cake that has its roots in the baked goods brought from Europe by the conquistadores in the early 1500s, while others point to folk tales and ancient stories about the Aztecs who supposedly made a type of bread as a sacrifice to their gods, infusing it with honey, oranges and even human blood. Blood sacrifices were essential to the ancient Aztec rituals of worship, so it is perhaps not surprising to see how a blood-infused cake used as a sacrifice to the gods of the afterlife has evolved into a pastry that commemorates the dead.

The changing of the season is commemorated in countries and cultures across the globe, often at the same time, as societal celebrations that honor the deceased. It’s this idea of the end of a season of plenty and growth into the beginning of another season characterized by dormancy, rest and death, that is so essential to the overall concept of celebrating and remembering those who have died. Our seasons, our crops, our pets and our lives, have a beginning, a middle and an end, thus continuing the cycle of life and death that is common to us all. It is both in honor of this ongoing perpetuation of time, and in memory of those we have loved and lost, that we celebrate El Día de los Muertos. ¡Viva la vida!

MY RECIPE IS AS FOLLOWS:

INGREDIENTS

1 stick unsalted butter, softened

1 cup full-fat milk, room temperature

5 cups all-purpose flour

2 packages active dry yeast

1 teaspoon salt

3/4 cup granulated sugar

2 tablespoons anise extract or anise seeds

1 tablespoon vanilla extract

3 tablespoons orange extract

Zest and juice of 2 oranges

4 eggs, room temperature

For the orange glaze:

1 cup sugar

2 cups grated orange zest

1/2 cup orange juice

METHOD

Over medium heat, warm the butter and milk until the butter melts.

In a large mixing bowl, combine 1/2 cup of the flour, the yeast, salt, and sugar.

Slowly beat in the warm milk, the orange, vanilla and anise extracts and orange zest and the eggs, and mix well.

Add another cup of flour, alternating with the juice of the oranges, and continue adding flour until you have a soft, but not sticky dough.

Knead the dough into a smooth and elastic ball, adding a bit of warm water if it feels dry.

Wrap in plastic, cover with a tea towel, and leave to rise in a warm area until it doubles in size, about 2 hours.

Heat the oven to 350F, unwrap the dough and press it into your pan. Bake for 30 minutes and remove from oven to cool.

In another saucepan over medium heat, combine the rest of the sugar, the orange zest and the orange juice until it just boils and the sugar dissolves. Whisk frequently to avoid the sugar burning. Let cool to thicken into a glaze.

Turn the bread out onto a platter and glaze. Decorate with marigolds if you so desire.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

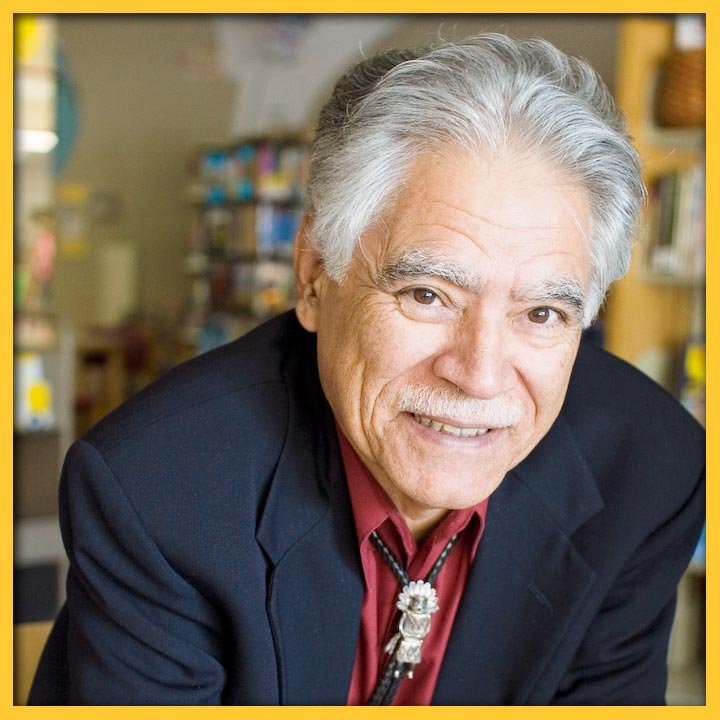

RUDOLFO ANAYA: CATCHING CULTURES IN BLESS ME, ULTIMA

By Richard Wayne Etulain

Anaya greatly expands the cultural contributions of his novel by combining the usual (Bildungsroman—growing up theme) with the unusual (complex, diverse New Mexico Hispanic culture)…

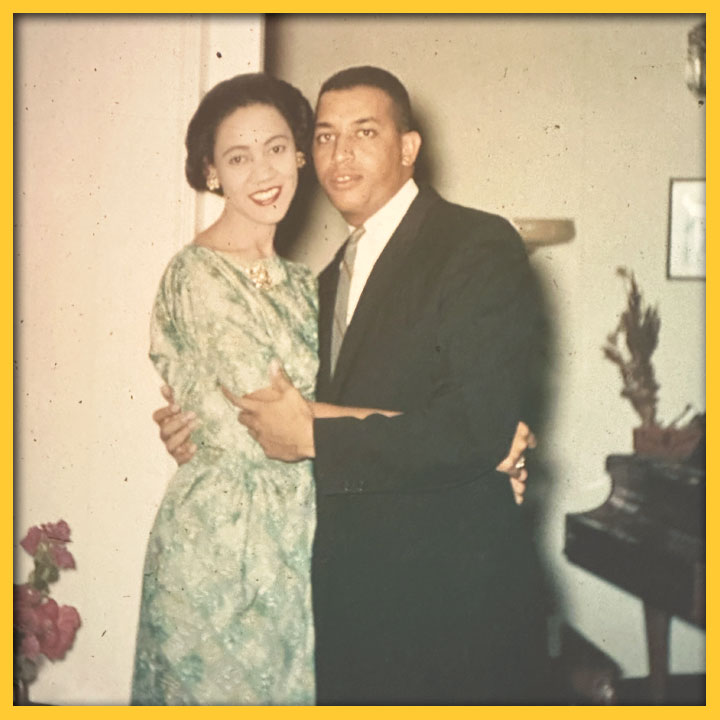

UP BY OUR BOOTSTRAPS; TWO LIVES IN RETROSPECT

By Finnie Coleman

I found myself fascinated with Dr. McIver’s transition from the stultifying hopelessness of the Segregation Era to the wistful hopefulness of the Civil Rights Era…

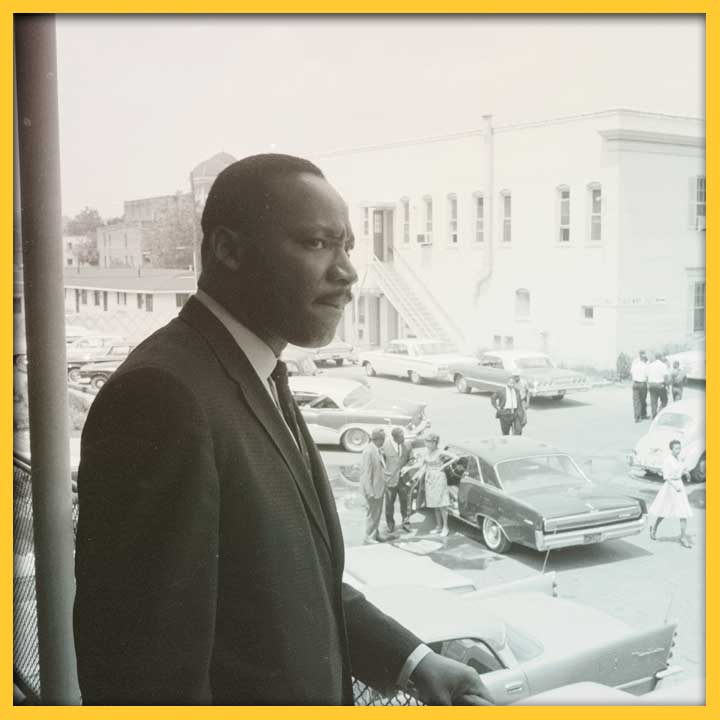

MARTIN L. KING, JR.’S DAMNING LETTER FROM JAIL

By Christopher A. Ulloa Chaves, ED.D.

“In the letter, King used a multi-disciplinary rhetorical approach that applied philosophical, theological, psychological, sociological, political, ethical and economic principles against systemic racism in Alabama…”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

VANESSA BACA

Vanessa Baca is a cook, writer, public relations professional, blogger, and podcaster. Her food blog Food In Books reviews various works of literature and recreates the food references within these books. www.foodinbooks.com. She is the co-host and co-producer of two podcasts. Fear Feasts is a podcast that analyzes the connection between food and horror in film and literature. www.anchor.fm/fearfeastspodcast. Sharing The Flavor is a podcast that is dedicated to analyzing the history of regional cuisine in many countries and recreates traditional recipes. Her one-man podcast Cooking The Books showcases literary food through a variety of guests, including writers, chefs, cookbook authors and food influencers. www.anchor.fm/cookingthebooks. A proud Nuevomexicana, she formerly lived in Spain, traveled extensively, and has taken cooking lessons in several countries.