SHARE:

I have been unable to keep up with the gardening

This year and have had to hire help.

I have never hired help before, and I feel as if I

Might be breaking a code-of-honor,

An unstated rule where we are supposed to do everything ourselves,

Even when we can’t, even if it kills us.

Before the workers begin, I ask Carlos if they have already had their morning coffee.

Si, y cerveza también. He replies with a smirk, as he leans into the hoe.

It is just past 6:30 and the sun is beginning to rise above the orchard’s tree line.

Supervising the milpa’s first escarda is a crow perched on a tree branch,

Hovering over us like Father Le De Ville in his Jesuit robe.

Arimandolé tierra, it is called, weeding and gathering the dirt around the plants

To fortify their graceful ascent towards the sky.

After we discuss the work that needs to be done, I tell them that

I have to go tend to my avalanche of emails, text messages, and writing.

Pues, que bueno, ese trabajo no es dificil, says Carlos.

Cada campesino piensa que su cabador es el más pesado, I tell him.

Es verdad, es verdad, he says. Ramiro laughs.Verdad que sí, he says,

As his hoe cuts sharply through a clump of goat’s head weeds.

We chat about how they are called toritos because they have sharp horns,

And are resilient and stubborn like a bull.

Con permiso, I tell the them as I make my way back to the house.

I look back and see the men, three angels hoeing the garden.

This reminds me of San Isidro who prayed while an angel plowed the field.

San Isidro is the patron saint of farmers, but he should also be recognized

As the patron saint of poets, writers, and artists who abandon their fields to tend to their craft.

I am working at the kitchen table and through the screen door

I can see their shoulders swaying, stooped over as if unbuilding

A wall with prayers, hope, and acts of salvation.

The morning’s heat has not made its appearance and the air is still fresh.

The keys on my laptop click rhythmically to the sounds of hoe blades,

Magpies, crows, and a symphony of birds and the neighborhood’s roosters.

Inside the old house, I am blanketed under a solitude that reverberates

With the slow hum of my antepasados’ ghost presence.

This place is my querencia where I should feel at home, safe,

And sheltered from the demands of external obligations,

If it were not for the constant reminder that I, too,

Have plenty horses to break, saddle, and ride.

Hay más tiempo que vida, my cousin would often say.

And maybe he was right, although sometimes I have a hard time

Grasping what he meant, there is more time than life.

After a while I reach a stopping point, meaning that I can no longer

Watch the men working my grandfather’s dirt without my participation.

I make my way back to Carlos, Prieto, and Ramiro.

I pick up a rake and begin cleaning the rows of the weeds

That have been cut and uprooted.

¿Como se sienten ustedes, trabajando estas tierras

Que en aun tiempo eran de México? I ask them.

Pues, gracias a Dios que tenemos trabajo, says Carlos.

Ya la gente mía no quiere trabajar, I tell him.

Ni la de nosotros tanpoco, he says.

For some, there is no day off.

Todos los días son el Primero de Mayo,

Día Internacional de los Trabajadores.

For others, the days seem to come and go,

thin as a veil of smoke swirling from a Pachuca’s cigarette.

Some of the local people say that Mexicanos

Are the best workers. No se quejan y no se rajan.

They do not complain and they never back away from a job.

And because it is getting harder to find good labor,

They are now the ones cultivating these lands

That once belonged to Mexico.

Maybe it is a form of poetic justice.

Estas se llaman Corre y Vuela, says Prieto,

Untangling the Morning Glory vines from around the corn stalks.

He says it fast and at first I think he is saying gorilla.

When I ask him to repeat it, he pronounces it slower.

Cor—re—y—vue—la. ¡Ah, corre y vuela!

Si, se desparama, corriendo por la tierra

Y despues cuando se seca, vuela la semilla por el aigre.

Maybe la vida is a question of who leads, who follows,

And how one gets from where they are to where they’re going.

Like the corre y vuela, are we not all in movement on our ascent towards home?

We go chooglin’ along like a choo-choo train rolling down the line,

Corridos, rancheras, blues, rap, and hip-hop,

The soul music of our lives, and the Snoop Dog Express singing us home,

Ana Gabriel and Antonio Aguilar in the caboose.

Note:

Carlos, Prieto, and Ramiro Come to Hoe the Milpa was inspired by the New Mexico Museum of Art exhibit, Poetic Justice: Judith F. Baca, Mildred Howard, and Juane Quick-to-See-Smith (Oct 9, 2021 – Mar 27, 2022). Some of the lines in the poem reference the titles of the artists’ paintings and narration from a short film by Mildred Howard.

Azucarero

I

¿Qué hay de nuevo pa la Vela?

I ask the young man standing

Behind the convenience store cash register

And a plexiglass shield between us.

It’s the same ol’ same ol’, he tells me,

Just a different generation.

At a historical marker five miles up the road,

I stop to take a picture of the Río Grande.

The mighty Rio Bravo del Norte

Still follows the carved path

Laid out by several million years

Of wind and rain and tectonic eruptions.

Tucked into a hollow at the base of the marker

Is a Virgen de Guadalupe votive candle vase

Stuffed with a thin stemmed solar light

And a bundle of red silk tulips.

A month ago someone from our village

Died in a head-on automobile accident here.

Que en paz descanse nuestro primo y paisano.

One side of the historical marker serves

As a Points of Interest map of the Pueblo and Indio-Hispano villages, churches, and ancient ruins along the Camino Real.

It is the ancient road also known as El Camino de Agua

Because it was the water route the nuevos pobladores

Followed as they made their way up from Zacatecas

To la Nueva Mexico.

The other side marks the site as the first

United States Geological Survey training center

Established in 1888.Those trained here made

Some of the earliest hydrological studies in the nation.

Hyper Nuevo, in a swirling turquoise graffiti script,

Is tagged over one of the corners of the sign.

Throughout the valley are countless of petroglyphs,

The Indigenous people’s rock art engraved on boulders

That tell of their presence and history,

Their comings and goings, their staying behind.

The cars on the highway whoosh past.

Folks eternally in migration and movement,

And there’s no slowing down.

El tiempo, como Dios, se tarda pero no se le olvida.

II

Once, as a young man, when I was hitchhiking through this canyon

I was picked up by a hippie in a beat-up Ford Econoline van.

As we made our way through the winding two-lane road,

He remarked about how this place was starting to feel like home.

Hey, man, you know you can buy property anywhere out there, he said.

Crouched over the steering wheel like the Kokopeli dancer

Dangling from the rear-view mirror.

His long bony finger pointed out towards the plateaus and mesas.

I’m gonna get me a few acres and build a house.

I won’t have electricity or water, but I’ll be fine.

Through his dreamer’s naiveté and enthusiasm,

I saw how a slight change in perspective

Can really put a hop in a person’s skip.

Today, as I look across the gorge

toward La Cañada de Los Comanches,

I can see houses beginning to sprout

Like clumps of grass growing in the crevasses.

I wonder if one of those houses belongs

To that wandering gypsy-hippie dreamer.

Perhaps he too is looking out across the valley,

Looking down from a precipice of a mountain.

Hay mas tiempo que vida, they say around here,

Knowing that life is limited but time goes on.

III

I was having a conversation with a childhood friend recently.

She was complaining about the younger generation.

She finds lack of manners upsetting and argues

for the need to teach good behavior and accept responsibility.

My friend laughs and places her hands on her hips.

She stands delicate but solid, like the sugar bowl on the table.

Sometimes I tell one of my nieces or nephews,

Go to the shed and get the rastrío.

A what? They ask, dumbfounded.

The rake. The rastrío.

They come back with the rastrío, and say,

Here you go, tía.

No, not for me. For you.

Rake up the leaves! I tell ‘em.

¡Hijolé! These kids now a‘days.

IV

We have morphed into our new shells.

Coyote tricksters never out of style,

but never quite current.

Defying time and space, static and mobile,

Like a trailer home set on cinder blocks without the wheels.

The tense, present and fleeting always has us

Looking back to see how far we haven’t gone.

It is a perfect union, Like the cracks and creases of human skin.

That Texas bluesman had it right,

Time keeps on slippin’, slippin’, slippin’,

Into the future.

There are life-accounts that will not be placed on a historical marker.

They are shaped from a poetry crudely composed, unstructured,

And versed, not through well-crafted literary devices,

But from stories that refuse to die even when the day’s biggest news

Sounds like the same ol’, same ol’.

That expressed chaos with unconnected lines

Woven together, like when the front tires

Catch a patch of black ice and veer the truck

Unto the path of an oncoming vehicle.

El tiempo es presta’o, someone reminded me recently.

And it’s true, we are living on borrowed time.

Note:

Poem inspired by Afton Love’s, Perfect Union, and Neal Ambrose-Smith’s, The (Tense) Present, concurrent exhibits at 516 Arts, Spring 2021, Albuquerque

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

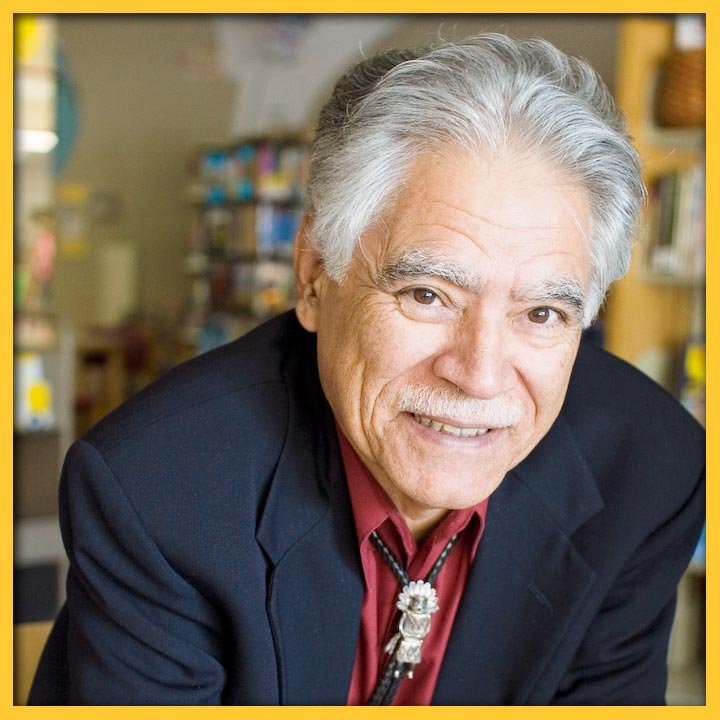

RUDOLFO ANAYA: CATCHING CULTURES IN BLESS ME, ULTIMA

By Richard Wayne Etulain

Anaya greatly expands the cultural contributions of his novel by combining the usual (Bildungsroman—growing up theme) with the unusual (complex, diverse New Mexico Hispanic culture)…

UP BY OUR BOOTSTRAPS; TWO LIVES IN RETROSPECT

By Finnie Coleman

I found myself fascinated with Dr. McIver’s transition from the stultifying hopelessness of the Segregation Era to the wistful hopefulness of the Civil Rights Era…

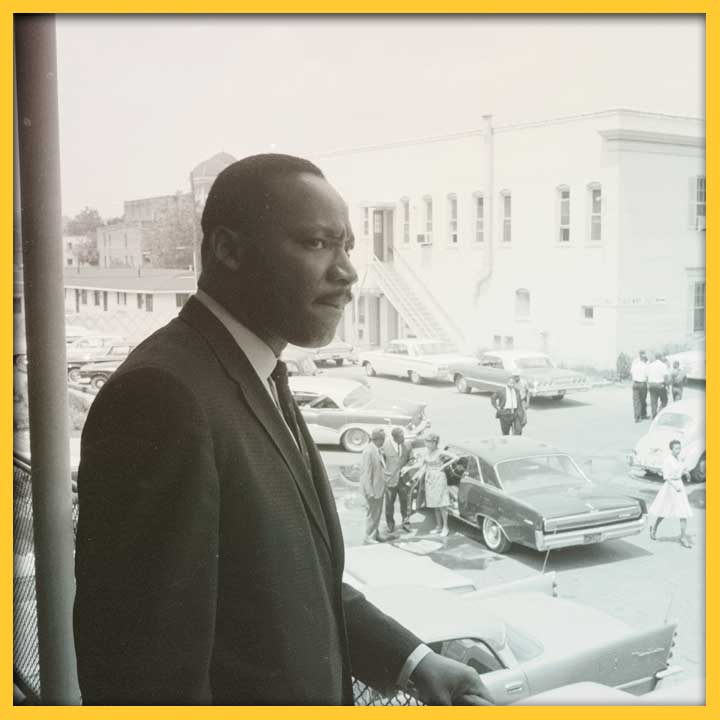

MARTIN L. KING, JR.’S DAMNING LETTER FROM JAIL

By Christopher A. Ulloa Chaves, ED.D.

“In the letter, King used a multi-disciplinary rhetorical approach that applied philosophical, theological, psychological, sociological, political, ethical and economic principles against systemic racism in Alabama…”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

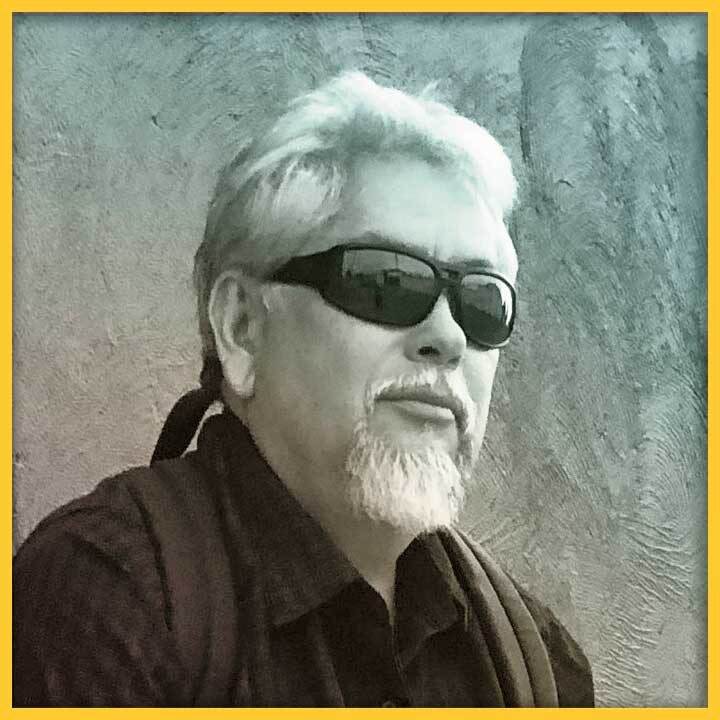

LEVI ROMERO

Levi Romero was selected as the inaugural New Mexico Poet Laureate in 2020 and New Mexico Centennial Poet in 2012. His most recent book is the co-edited anthology, Querencia: Reflections on the New Mexico Homeland. His two collections of poetry are A Poetry of Remembrance: New and Rejected Works and In the Gathering of Silence. He is co-author of Sagrado: A Photopoetics Across the Chicano Homeland. He is a member of the Macondo Writers Workshop. He is an Associate Professor in the Chicana and Chicano Studies department at the University of New Mexico. He is from the Embudo Valley of northern New Mexico.