CIVIL RIGHTS AND JUSTICE — THE FORCE OF REIES LOPEZ TIJERINA

What was the immortal legacy of the extreme activism of Reies Lopez Tijerina?

New Mexico Governor Jerry Apodaca with civil rights leader Reies Lopez Tijerina in an undated photo. Photo courtesy of UNM libraries photographic collection (#000-654-0098, CSRW).

SHARE:

The decade of the 1960s was marked by racial and social unrest, the Vietnam War, protests, tension, and cultural chaos. Heroic national social justice and civil rights leaders such as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Cesar Chavez, and Reies Lopez Tijerina emerged and led movements directed towards human rights, human dignity, and equal justice. Inspired youth took up the standards of civil rights, and their voices reverberated in the streets and across the nation. Out of the struggles and ashes of human despair, Reies Lopez Tijerina rose up, took up the torch and vibrantly animated the scene not only in New Mexico, but throughout the Southwest and the nation. Hispanic youth were caught up in the fervor and zeal of this remarkable period in New Mexico state and national history. El Tigre, King Tiger, as Tijerina was called, spoke out:

My motto is justice. Every time I think about my people it brings me to tears. Lagrimas stream down my face. They run like a river when I see the faces of anguish and hopelessness across Nuevo Mexico and America. Join me today. Join la Alianza. Only an alliance of our people can see that justice is done. It is our right. Our Spanish language, our way of life and our land must be protected. You are the heirs of this beautiful land, your sons and daughters are the heirs. Queremos Justicia. Then raising his voice to a boom, Tijerina added, We want justice! Not welfare and powdered milk! We have had enough!

Reies Lopez Tijerina was born in a farming community near Falls City, Texas, on Sept. 21, 1926. His father was nearly crippled from working out in the fields. His mother died when Tijerina was 6 years old. His family had scraped out a living as itinerant farm workers. Survival was through hard labor and sharecropping. Even children were involved in peonage, working for very wealthy ranchers and farmers. Tijerina and his siblings, all very young children, moved on as migrant farm workers, along with countless others, after his mother died. Like many other children of these migrants, Reies and his siblings were self-taught. Texas, like other former Confederate states during those days, was extremely unfriendly and racist towards Blacks and the Mexican immigrant community but needed these workers to do the hard labor. Others would not do it. “No Mexicans Allowed” signs were strewn around many areas. Neither Mexican migrants nor any other Hispanics could go into some restaurants, live in “Whites Only” residential areas, and were restricted under the penalty of the law from anything that only Anglos could take part in, including drinking water from race–exclusive water fountains. Anyone breaking regulations was incarcerated for breaking harsh rules and laws by prejudiced juries and racist court systems.

Tijerina at the age of 17 had the opportunity of attending the Assembly of God Bible School in Saspamco, Texas. He attended for three years and was an exemplary student, receiving praise and honors in his classes. At 20, Tijerina went on to do missionary work in the southwestern United States and became highly recognized for his zeal and preaching. The young preacher tried to construct churches and communities in Texas, Arizona, and California, during the 1950s, but his buildings were destroyed and burned. He was often beaten and brutalized. This made the fiery preacher more determined not only to stand up for his people who lived under poverty and abuse under horrific conditions, but also to be their apostle, seeking justice. He bought law books and intensely studied them for self-protection, and to protect his congregation of loyal followers.

The popular preacher’s first contact with New Mexico had been in Santa Fe around 1947-49, not only enjoying the climate and scenery but also the friendliness and openness of the locals. They all communicated quite easily in Spanish, since northern New Mexicans in particular and New Mexicans in general, were quite adept in the Spanish language. The young preacher in his late 20s traveled around meeting and shaking hands with the people, especially old-timers who had a wealth of knowledge about land loss. Reies traveled freely from one state to another. He was in New Mexico’s Chama Valley in 1950. He also traveled to Tierra Amarilla during the same year. This northern New Mexico community would make a lasting imprint on Tijerina that would influence the rest of his life and career. In 1954 he published a book in Spanish called Hallara Fe En La Tierra, loosely translated as Will Faith be Discovered in the Land?

Reies Tijerina went on a ceaseless quest for knowledge about land theft in New Mexico. He traveled to Santa Fe to study ancient documents he found in the state archives. He became an expert in reading the difficult Spanish Colonial records he found. He also went to Mexico and Spain and researched there. The more Reies discovered, the more he wanted to find out. Tijerina learned about “La Alianza Hispana Americana,” a group that had been very active in early Las Vegas, New Mexico. He also researched “Los Obreros,” a labor union that had also been a large group in northern New Mexico who had sought to effect changes in working and social conditions and government for the betterment of Hispanics.

Tijerina was especially attracted to the legacy of “Las Gorras Blancas,” an organization of ranchers and farmers based in San Miguel County, and other northern counties. At one time, there were around 5,000 members that sought civil rights and equal justice between 1870 to the late 1890’s. These late-night riders wore shoulder-length white hoods to conceal their identity and to protect their families.

During the Civil War period in New Mexico, close to 12,000 Hispanic ranchers and farmers volunteered to fight for the Union. They provided their own arms, horses, and provisions. Hundreds died fighting Confederate forces that invaded and took over the territorial capital in Santa Fe. Troops under Lt. Col. Manuel Antonio Chavez succeeded in defeating the Confederates at the famous battle of Glorieta. After the end of the war, former Confederate officers, soldiers, and southern sympathizers arrived in New Mexico en masse and meticulously sought to control the government and steal lands in cahoots with land swindlers and thieves who were infiltrating into Indian lands and the rest of the country. Needless to say, a very powerful and corrupt group succeeded enormously. The notorious Santa Fe Ring, a lawless and crooked group of government officials, judges, lawyers, surveyors, outlaws and lawmen, controlled New Mexico Territory. The leader was Thomas Benton Catron, a former high-ranking Confederate officer. He became the largest landowner in the country, backed up by gunslingers.

Not only was property stolen, people were uprooted from their homes, dispossessed of personal belongings, and some were indiscriminately murdered if they did not leave. Newly introduced barbed wire fencing proliferated, and railroad ties were laid on community property that had been confiscated at the point of the gun. The U.S. government also freely took over millions of acres of Indian lands and ancient Spanish land grants. Many of these lands then were leased to immigrant White ranchers, shady enterprises, and dubious politicians. Leases ran up to ninety-nine years at pennies on the dollar. This Native American territory and centuries-old Spanish and Mexican land grants were supposed to have been protected by the federal government through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which officially ended the Mexican American War. American merchants and miners flocked into New Mexico Territory, which at that time included Arizona, Nevada, and parts of Colorado, Texas, and California. Local Hispanics not only lost lands and personal belongings, but even generations-old churches and burial sites of family members were taken. A law was passed that mercantile stores would handle burials only in designated areas. Corners in stores often kept bodies waiting to be buried. Before this, deaths in families were a family affair with people constructing homemade coffins and handling anything and everything with caring for their deceased. Now it turned into a very lucrative enterprise for shady merchants who became very rich. Hispanic ranchers and farmers finally banded together and formed a group that cut barbed wire fences that shut off communal grazing lands and water sources. Grievances had fallen on deaf ears in the courts, so it was felt that the only recourse to protect peoples’ rights was by striking back. However, the result was failure.

But eventually people in New Mexico had had enough! Poverty among Hispanics was rampant. Educational opportunities were minimal. In the southern part of the state, Hispanics were not allowed in certain restaurants. Many turned a deaf ear to the plight of grievances of the generations, old loss of lands. Reies Lopez Tijerina, fighting for human rights, felt he could make a difference.

In May 1967, I became a member of the Alianza Federal de las Mercedes under Reies Lopez Tijerina. When I went into the Alianza headquarters on Third Street in Albuquerque to pay my dues, it was Tijerina who registered me as a member. When he heard I was from Las Vegas, Reies Tijerina was ecstatic. He took me to the area by his desk to show me the land grant documents he had hanging on the walls. The land grant leader had done extensive research in Mexico and in Spain.

Our initial contact lasted a couple of hours. Reies that day was full of joy that someone my age would be interested in his noble quest for justice, especially when he found out I was an heir of the Don Nicolas Duran y Chávez Grant. Tijerina was not only charismatic, his magnetic personality and commanding ways captured everyone’s attention. I became an active follower of his cause. I also drew in many of my friends. We took part in a protest march from Mills Avenue in Las Vegas to the town of Tecolote 9 miles away to the town hall, decrying land grant issues and the poverty in northern New Mexico. Others there joined our land grant leader. Obviously, not everyone was sold on Reies Tijerina, but his moving words and fiery speeches made people think and take notice. He was a firebrand with many followers, including Donaldo “Tiny” Martinez from Las Vegas, the district attorney who wielded a great deal of power in northern New Mexico. He was a member of a group known as the “Mama Lucy Gang.” Lucy Lopez’s restaurant in Old Town Las Vegas was the gathering place of many important political figures and influential people who wound up supporting Tijerina.

Father Luis Demecio Jaramillo, the chaplain of the South Valley Black Berets, a group of Chicano activists, expounded, “Some people need to get slapped before they wise up and take notice. Learn and do what is right! Do what bothers the hell out of people, makes them think and make changes for the good of everyone!” Father Jaramillo, a Springer, New Mexico, native, did not hold back in his Catholic church sermons — nearly always speaking in Spanish when he needed to make a stronger point. He also supported Reies as well as other members of the clergy who fought for civil rights in New Mexico. Before a protest march from Las Vegas to Santa Fe, Tijerina proclaimed:

We have just started to write a new page in the history of Nuevo Mexico. We need actions not words! The time is right for us to get rid of our fears. They have stolen our land! Our lifeblood is la tierra, the agonizing land that runs through our veins is shedding tears! ¡Vamos adelante! Let’s go forward and move Nuevo Mexico to its best, and in doing so, the rest of our country! With this, we will help everyone in our beloved nation!

Civil rights attorney William “Bill” Higgs joined Reies in his honorable quest for equal justice. Higgs had received national attention in the media for representing James Howard Meredith, a Black student who was denied enrollment at “Ole Miss,” in Jackson, Mississippi. This was a flashpoint in the national civil rights movement across the country. Many took up the standard of desegregation across the country, including Rosa Parks. She refused to sit in a Blacks-only section of a public bus. Bill and I hit it off immediately, and we became close friends. It was he who invited me to attend Tijerina’s meetings and speeches. I was thrilled. At the Alianza headquarters we gathered to make plans for conferences and marches, such as the Poor Peoples March on Washington, D. C., where Reies met with Native American leaders and Black leaders such as the Reverend Jesse L. Jackson of the National Rainbow Coalition, Malcolm X and the Reverend Ralph Abernathy.

Cesar Chavez, addressing Alianza members at the headquarters on Third Street in Albuquerque said, “Yo soy uno de ustedes. I am one of you in the struggle for equality, for human rights and dignity. It is the struggle of all of us.” Chavez’s last words stayed resonating in our ears: “Me han dicho muchas veces que no se puede hacer. Que no podemos cambiar las cosas. Yo les digo, si, se puede hacer. Podemos cambiar la injusticia. ¡Si se puede!” (They have told me many times that it cannot be done. That we cannot change things. I tell you, yes, it can be done! ¡Yo estoy con ustedes!” (I am with you!). Words like this, during this time and place, led us all to action. As teenagers and young adults, we were bent on action making changes for the betterment of all those who were downtrodden in American society. Native Americans had a movement. Black Americans had their movement. Hispanics had El Movimiento, calling for parity, equality, equal justice, respect, and dignity in New Mexico and in the American mainstream. However, circumstances and destiny had other unexpected plans in an event that drew worldwide attention that led to very strange and very rapid horrendous results. On June 15, 1967, many people from throughout New Mexico gathered peacefully at Tierra Amarilla, New Mexico.

It was a nice day in northern New Mexico, bright and sunny. Close friends and families gathered to listen to Reies Tijerina expound on racial injustices in New Mexico and America.

People hugged, shared stories, and everyone spoke about past injustices in New Mexico, about lost lands and the mistreatment everyone received by the corrupt judicial system of the past. All would gather for music and dance to New Mexico Spanish music plus enjoy a huge potluck at the town center. This very significant day in New Mexico history left a lasting and enduring mark on New Mexico state and national history. What began as a peaceful gathering to hear the words about injustice spoken by the great Tijerina grew and spread into violence that was spurred on and spread by political officials and police officers bent on prohibiting any protest, no matter how peaceful, against historic corruption and injustice in New Mexico history. Chief among these officials, according to what is written, and available to the public, was Rio Arriba County District Attorney Alfonso Sanchez. It is believed he arbitrarily issued orders suppressing peaceful protests and peaceful gatherings. Gov. David F. Cargo had left the state for other business, and New Mexico Lt. Gov. E. Lee Francis was in charge. Although Cargo, as governor, was the commander in chief of the New Mexico National Army and Air Force Guard, he was apparently unaware of what would take place.

Things at Tierra Amarilla went out of control. People were inadvertently injured, arrested, and one was killed. The unfortunate incidents and death of this individual were a complete mystery. Many had ideas about what happened but had no proof. Only circumstantial evidence arose. The killing was never thoroughly investigated. New Mexico State Police were involved in actions. The local sheriff’s office was involved. Lt. Gov. Francis activated the New Mexico Army National Guard through Adjutant Gen. John P. Jolley, so tanks and other heavy armored military equipment rolled into the peaceful village of Tierra Amarilla. National news proclaimed that an armed insurrection was under way in New Mexico that was trying to overthrow the government. Local citizens were rounded up, apprehended, and placed in corrals, barns, animal cages, anything readily available to hold them. Even outhouses were used. It was the state against the populace in the area who they erroneously believed were involved in an armed insurrection. I was at summer camp with the New Mexico Air National Guard in Wisconsin. Our Air Force branch was activated in case the units from Kirtland were needed. Our manned units, which were trained in riot control, were ordered to be ready for immediate deployment to northern New Mexico. Many knew I was an active member of Tijerina’s Alianza, so I was asked by my superiors if I was loyal to the military or to his hopeless cause. As a member of the U.S. military, my interests were vested in serving the U.S. government as were the interests of the rest of my fellow soldiers.

In American history, U.S. citizens have always had the right to perform a citizen’s arrest when someone is committing a crime, such as burglary, rape, destruction of public property, causing violence, harming, or injuring, or killing someone. Reies Lopez Tijerina had spent many hours studying the law. He firmly believed American citizens had inalienable rights to protect themselves in their persons, in their property, and in their possessions. So, when Tijerina firmly believed crimes had taken place in New Mexico history and were taking place in the present, he could not turn away, but firmly believed he needed to step in. Tijerina very quickly made it onto the national stage.

No one knew what was happening behind the scenes politically in New Mexico. As was happening throughout the country with all civil rights leaders –especially the Social Justice Triad of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Cesar Estrada Chavez and Reies Lopez Tijerina – all were considered enemies of the state and were targeted for eradication by the government by whatever means available. Dr. King was arrested 29 times for civil disobedience. Chavez was arrested for leading national boycotts against farming conglomerates that controlled immigrant workers with low salaries, horrendous working conditions, including threats and forced labor. Cesar Chavez led pickets, protests, and marches against unjust practices that were not even allowed by federal law. He was arrested along with 3,000 followers and put in jail. Chavez had served valiantly during World War II in the armed forces and followed the premise of nonviolent resistance pioneered by India’s Mahatma Gandhi. The Indian leader was an anti-British colonialism nationalist who led a movement against British rule. He staged hunger strikes and was assassinated on Jan. 30, 1948. Gandhi inspired political movements of civil rights and freedom all over the world.

Cesar Chavez in California followed Gandhi’s leadership by also engaging in hunger strikes. One eventually led to his death. Dr. King was assassinated on April 4, 1968. There had been a plot to kill Chavez, and there were also plots to take Tijerina’s life. His Alianza headquarters was bombed in Albuquerque. The land grant leader spent time in prison for civil disobedience. He was convicted for his struggles to have a particular massive land grant that had been stolen from a generations-old community land grant by the government and turned into a National Forest area. Federal Bureau of Investigation Director J. Edgar Hoover and his agents kept files on all three civil rights leaders. Tijerina was ordered to turn over his membership files to the FBI and New Mexico U.S. District Judge Garnett Burkes which included the phone numbers addresses, and personal information of around 5,000 New Mexico citizens. Reies refused to do so. In May 1967, Judge Payne sentenced Tijerina to fifteen years in prison for what was essentially hard labor — to break him down and bring this forceful civil rights leader to his knees. There had been a long history of protecting one side in land disputes in New Mexico. Several justices followed in the footsteps of Elisha B. Long, a recognized member of the Santa Fe Ring in New Mexico history who became chief justice of New Mexico’s Territorial Supreme Court. Tijerina’s refusal led to a longer prison sentence. As it happened, two FBI special agents came to my home in Albuquerque and questioned me for two hours about my own affiliation with the Alianza. They left, satisfied that I was away at an out-of-state Air National Guard training when the event at Tierra Amarilla took place.

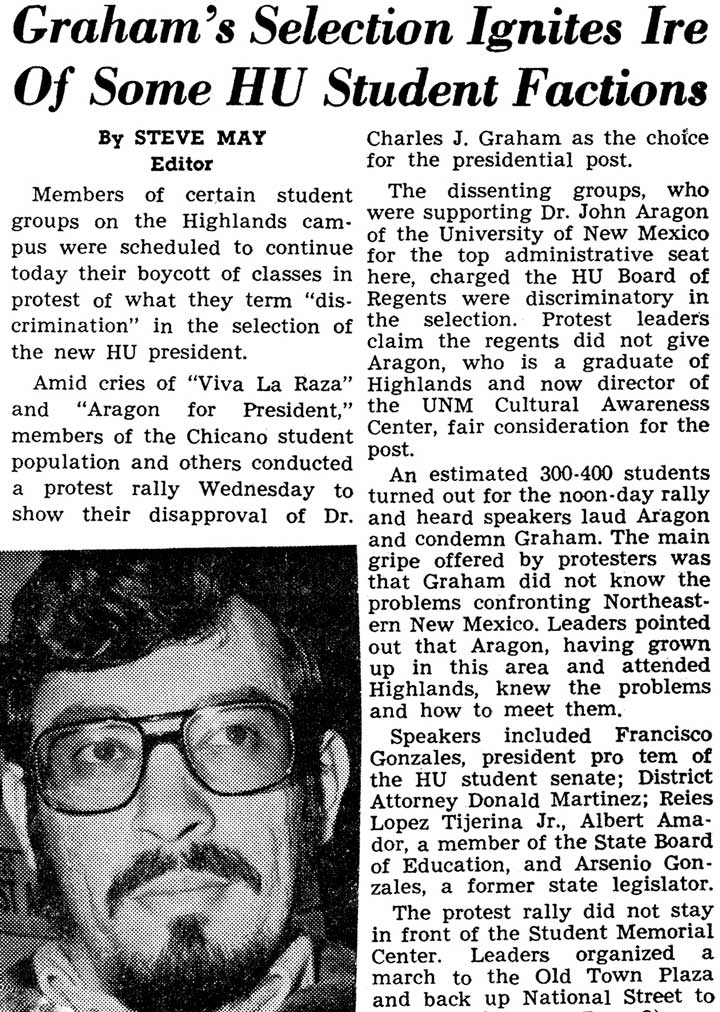

One might ask the following question: What was the immortal legacy of the extreme activism of Reies Lopez Tijerina? Many have failed to recognize how this civil rights leader affected the history of New Mexico and the United States. Tijerina was a champion of education, especially higher education. He often spoke about the lack of Hispanic leadership and faculty positions in colleges and in universities across the country. In 1970, a position for president opened up at New Mexico Highlands University in Las Vegas, New Mexico. Many highly qualified Hispanics applied for the position which had been held by White/Anglos since the institution’s founding in the late 19th century. The student body at NMHU, composed primarily of Hispanic students from New Mexico, supported Dr. John Aragon who had a distinguished career. Dr. Aragon was passed over by the board members, who hired Dr. Charles Graham from Wisconsin on May 22, 1970.

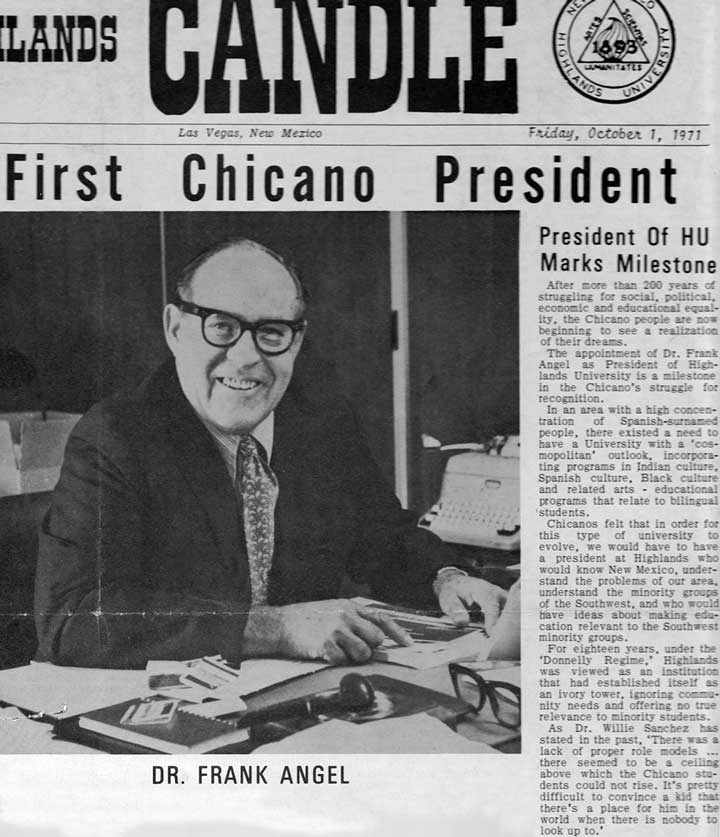

The students were outraged and were spurred on by Tijerina, who vocally encouraged them to make this a major issue in his fiery speeches. Protest marches took place, and posters, effigies, and other material were posted on the campus, and a student takeover of administration offices took place. Additional material was taken to what would have been Graham’s home. The campus police and Las Vegas Police Department police officers threatened the students with arrest. However, many students came from families with strong political influence. This helped to pacify the situation, although some still were arrested. The end result was that Graham declined the position. Chicano students led by Tijerina succeeded in having Dr. Frank Angel, a Las Vegas native with close ties to New Mexico, hired as the new president in August 1971. At first glance, the hiring of Dr. Angel would have only caused a ripple, but it quickly became a torrent of national news. Reies Lopez Tijerina’s involvement and speaking out on important issues relating to Latinos in education, also helped the push for not only the hiring of Hispanics in universities and colleges, as well as their being placed as department heads and college deans and other high posts — all positions that had been previously denied to Hispanics in the country. This demonstrated that changes can be made when we follow or lead as Reies Lopez Tijerina and many others have led.

Martin Luther King Jr. said,

The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands at times of challenge and controversy. In ancient times, the ability to read separated the wealthy and the poor, the educated and the ignorant, the free and the enslaved. The theme of perseverance continues to be prominent among themes in many peoples’ lives as they face adversity. These themes are even more explicit within the lives of those marginalized and facing injustice in both small and large ways each and every day.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

SPACESHIPS, RAY GUNS, AND LIFE LESSONS

By Melinda Snodgrass

“science fiction allows you to discuss difficult and fraught topics in what is a safe space and at arm’s length.”

LITERATURE AS GUIDEPOSTS ON MY IMMIGRANT JOURNEY

By Kei Tsuzuki

“What I have learned from books is that there is no one story that explains the world to us or captures our identity entirely. There is power in the specificity of each of our stories…”

A DIFFERENCE-MAKING BOOK

By Richard Etulain

“Many authors hope their histories, novels or other writings will make a difference — that their works will catch readers’ attention and influence their thinking and actions.”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

RAY JOHN DE ARAGON

Ray John de Aragón’s book, ENCHANTED LEGENDS AND LORE OF NEW MEXICO, Witches, Ghosts, and Spirits was required reading for the course, Humanities, Society, and Culture: Only in New Mexico? The class was carried by the University of New Mexico Honors College and was taught by Dr. Juliette Cunico, former Shakespeare Specialist of the English Department at Bradley University. His book, HIDDEN HISTORY OF SPANISH NEW MEXICO placed 13th of 47 Best-Selling Mexico History Books of All Time, as featured on CNN and Forbes Inc. His archives are stored at the Southwest Studies and Research Center at UNM. He has 20 published books and will keynote at the New Mexico Associated Press Conference in Santa Fe in November.