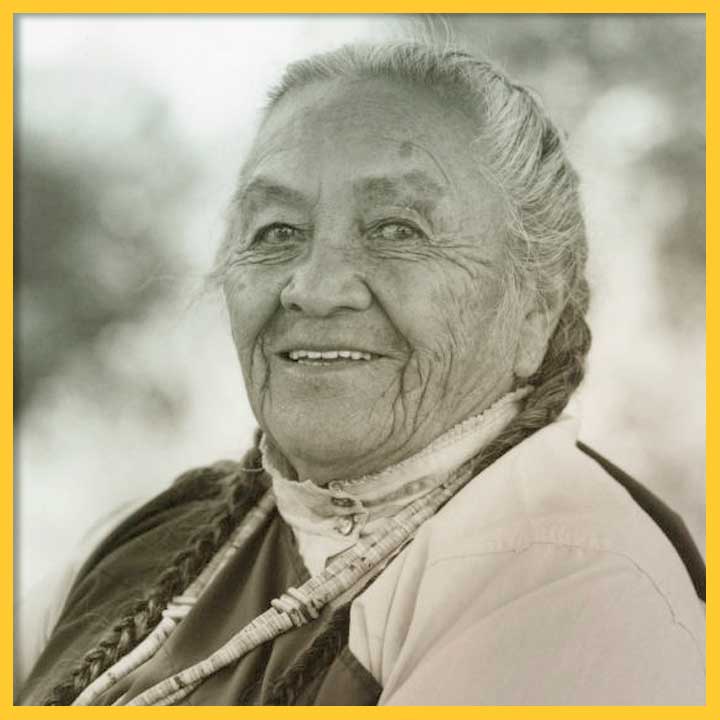

ESTHER MARTINEZ (P'OE TSÁWÄ/BLUE WATER): A MATRIARCH OF PUEBLO LANGUAGE PRESERVATION

By age seven, Martinez no longer had her elders, their stories, or her grandmother’s cooking to ease the transition as she reoriented herself to boarding school life about twenty miles south of her village of Ohkay Owingeh.

Esther Martinez, Native American storyteller, from Ohkay Owingeh, New Mexico. Photo Courtesy of Center for Southwest Research, University Libraries, University of New Mexico.

SHARE:

We come from a tradition that values the music of language, its poetry, and its ability to conjure images. There is a love for the sound of the language, a love for the beauty of a phrase.

—Tessie Naranjo (Santa Clara Pueblo)

The mother tongue, or native language learned from birth, transmits not only conceptual meaning, but culturally specific social and inferred meaning which make language feel like “home”— like the intonation of a grandmother’s words as she sips her morning coffee and chats with her comadre (Spanish word meaning “godmother” or “friend,” which in Pueblo culture refers to a co-mother responsibility for a child) about village happenings while her young grandchild plays nearby, or the rhythm of a grandfather’s songs as he later sings that same child to sleep in his arms for an afternoon nap. These elements that are embedded in culture are transmitted to that child whether they eventually learn to speak that language fluently themselves. Childhood memories are made from these words; childhood memories are made from these songs.

For numerous Pueblo children, these formative years were disrupted by U.S. federal policies aimed at systematically extinguishing Native languages and cultures through assimilation to American culture by schooling. Despite its intimate familiarity, the native language has remained out of grasp for many who have not realized fluency as previous generations had done so without much effort due to historical events that disturbed family and community. Schooling, relocation to urban areas for economic gain, and cultural and social changes such as the introduction of television are among these events that have disrupted fluency. However, these language memories could never be erased. And for some, actual language proficiency has become reality thanks to those who defied historical circumstances refusing to let these languages die, including Esther Martinez (P’oe Tsáwä/Blue Water).

In 1912, the year that Martinez was born, New Mexico Pueblos lived with the U.S. government policy that required them to send some of their youngest community members to off-reservation boarding schools. Perhaps, the most well-known of these schools was Carlise Indian Industrial School whose founder’s words echo the initial aim of these schools, “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.” Some Pueblo children went to the faraway school in Pennsylvania; and many more attended local boarding schools: Santa Fe Indian School and St. Catherine’s Indian School, both in Santa Fe, and Albuquerque Indian School.

Removed from family, community and everything she had known up until that point —language, food, music, dance, stories — Martinez, like many other Pueblo children, was expected to receive a mainstream education which meant leaving her native language at home. By age 7, Martinez no longer had her elders, their stories, or her grandmother’s cooking to ease the transition as she reoriented herself to boarding school life about 20 miles south of her village of Ohkay Owingeh (formerly known as San Juan Pueblo).

The regimented boarding school curriculum was in complete contrast to the way that teaching occurred in the Pueblo world. Martinez elaborated on the Pueblo approach to education, “We were taught the values of the Tewa world. And it was not a place where we sit down and have to listen. They modeled what they were teaching us. That was a nice way to learn.” So homesick were Martinez and her peers that they hid under blankets to hide their tears or risk being labeled “crybabies.” In boarding school, children were reprimanded for speaking what up until that point flowed naturally, and without shame, from their mouths: their mother tongue.

Martinez, who graduated from Albuquerque Indian School, eventually returned to her home community, perhaps more determined to hold on to those aspects of her culture that the government tried to remove. Upon returning home, she supported her family by working numerous service jobs, as well as carving birds from driftwood found at the nearby river bank (a place she frequented with her 10 children) to sell to tourists, and later became a bilingual language teacher.

While working at San Juan Day School, she and others compiled the first Tewa language dictionary, curriculum guides, and storybooks. Although she spoke Tewa fluently from childhood, she did not learn to read and write the language until she was in her 50s. Pueblo languages had always been transmitted orally until cultural and social disruptions from the outside caused communities to turn to written words as a new way of transferring this knowledge. Martinez’s recognition of this shift resulted in the creation of valuable written resources beneficial not only to her own village, but to other Tewa-speaking Pueblos.

She traveled throughout New Mexico and to other states, essentially acting as an ambassador, telling stories and teaching others about her Pueblo culture. She credited her grandfather with teaching her these stories, which she listened to on long winter nights as she snacked on roasted piñons. Martinez’s daughter, Josephine Binford, described the experience of hearing her mother tell a story: “Every time my mother tells stories to us or to others, she makes the story come alive. She speaks in a low tone, with each word carefully and very gently spoken. When her words are spoken the words are treated like gold.”

With each telling of a story, she demonstrated that the connection to the traditions of her ancestors continued despite attempts from outside forces to sever these bonds. In addition to teaching lessons about life, her stories illustrated the many aspects that make Pueblo life unique including a profound belief in multigenerational community and kinship ties; a value system focused on respect for self and others; and how oral tradition is woven into language, stories, music, songs and dance.

Martinez’s publications embody her work as a linguist, storyteller, and a historian, including the San Juan Pueblo Tewa Dictionary (1982), the children’s book, The Naughty Little Rabbit and Old Man Coyote (1992), and My Life in San Juan Pueblo: Stories of Esther Martinez (2004). On the national level, her passion for language preservation and revitalization was recognized in 2006 when she was awarded the National Heritage Fellowship by the National Endowment for the Arts, and further with the signing of the Esther Martinez Languages Preservation Act, a measure which worked to fund programs that promote Native language preservation.

When receiving the State of New Mexico’s Governor’s Award for Excellence in the Arts in 1998, Martinez commented on how she was the first Native storyteller to receive the recognition, comparing herself to painters who had received the award, “I never went anywhere with my ‘paintings’; my paintings are all done in the minds of my audience, my artwork lives in the heart of people.”

Martinez’s storytelling demonstrated her love of language — more specifically her love for her Tewa language — her love for the traditions that shaped her, and her deep commitment to assuring that these loves remain in the hearts of future generations.

Sources Used:

Mainor, Peggy and Evie Freeman, “Esther Martinez: Protecting the Intangible Heritage of the Tewa People.” National Trust for Historic Preservation. Aug. 18, 2020.

Martinez, Esther, and Sue-Ellen Jacobs and Josephine Binford, eds. My Life in San Juan Pueblo: Stories of Esther Martinez. Urbana, Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2004.

Martinez, Matthew. “Esther Martinez” in Voices from the Gaps. University of Minnesota. April 5, 2005.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

A DIFFERENCE-MAKING BOOK

By Richard Etulain

“Many authors hope their histories, novels or other writings will make a difference — that their works will catch readers’ attention and influence their thinking and actions.”

CELEBRATE CONSTITUTION AND CITIZENSHIP DAY EVERY DAY, NOT JUST SEPT. 17TH

By Maryam Ahranjani

“As a teacher and mother and child of immigrants who now teaches Constitutional Rights to law students, this day is always a special one for me.”

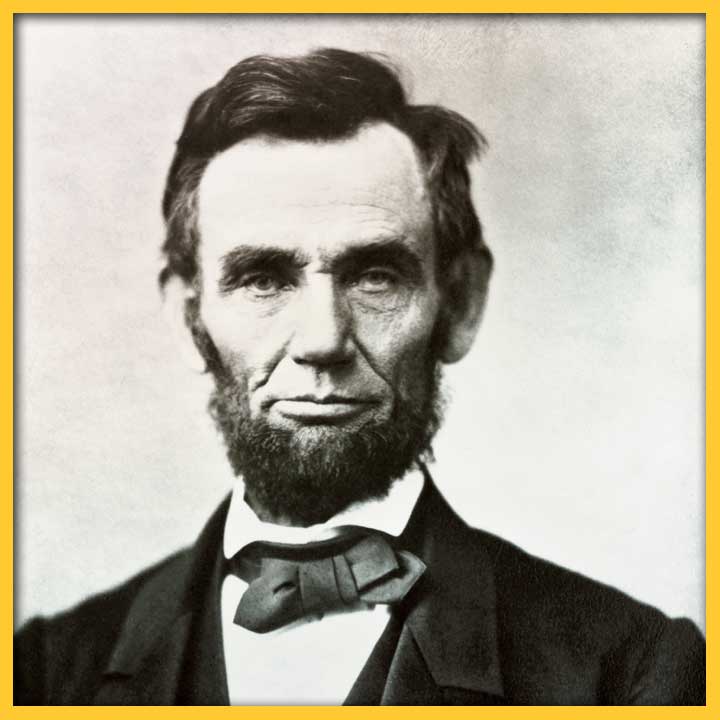

THE THIRTEENTH AMENDMENT THAT NEVER WAS

By Brandon Johnson

The 13th Amendment, guaranteeing the abolition of chattel slavery in the United States, is one of the crown jewels of the American Constitution.

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

KIM SUINA MELWANI

Kim Suina Melwani is from the Keresan-speaking village of Cochiti Pueblo. She holds an MA in U.S. West history from the University of New Mexico, and currently researches and writes on topics related to Native history and culture.