FROM MORA TO MARIACHI: MY DAD AND HIS MAGICAL JOURNEY OF MUSIC

- By Rob Martinez

- No Comments

Dad loved and respected the Penitentes. But he wanted to be a mariachi! The dream would have to wait.

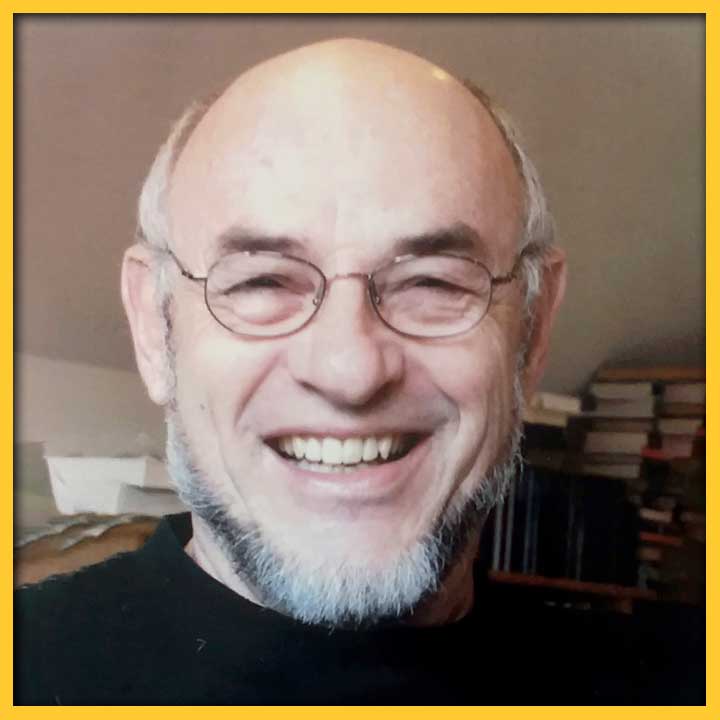

IMAGE: Martinez family members of Los Reyes de Albuquerque. L-R: Rob Martinez, founder Roberto Martinez, Larry Martinez, and Lorenzo Martinez in Old Town Albuquerque in 1994.

SHARE:

My dad wanted to be Pedro Infante when he grew up.

His name was Roberto Martínez. As a young boy living in the Mora Valley during the Great Depression, hard work and scarcity were the norm. When I asked what his middle name was, he would joke that his family was too poor to afford one for him. His dad was Maximiano Martínez, who also had no middle name. His mom was Prudencia Rosa Lovato, Gramma Rosa to us.

Dad told stories about growing up on a farm. It was a hard life in a harsh landscape — taking care of animals, grazing livestock, butchering hogs, goats and sheep. It was bloody business. Grampo Maximiano was a hard worker and could also be a hard man. It was all he knew. Once, when dad was about 9 years old, his dad made him ride a horse across the valley from Chacon toward Guadalupita to tend to some cows. Dad was scared and cold. Perhaps today it would be considered child abuse. Back then, it was survival. There were stories of Grampo making money to feed the family by cutting down trees in the mountains and hauling logs down to the valley. It was hard work carried out by seemingly indestructible people. Dad was only 11. He helped, recalling to all of us the feeling of exhaustion. And the deep sleep that followed on a bed shared with his younger siblings. The cool pine filled mountains of green grass, alfalfa growing in fields, plums picked right off the tree in summertime, their sweet juice running down the chins of those taking a respite from the hard work of the day — moments transformed into fond memories.

Dad’s Uncle Flavio broke away from the boundaries that surrounded the rural hamlets of Mora, Chacon, and Rito de Agua Negra, also known as Holman. Uncle Flavio sang and played guitar and saxophone! He was charming and looked like Omar Sharif. And he drank like a musician. He was a hero to my dad. Rare trips to Las Vegas, New Mexico, exposed the mountain family to English-speaking Americans. Spanish, after all, was all Dad heard spoken by his family. The lilting singsong of aspirated ‘s’ sounds and sweet comfort from his mom were also memories he shared.

Dad’s Uncle Flavio inspired him, but the revelation of what he could be came one summer afternoon when, in a small theater, young Roberto saw a Mexican movie that featured a swaggering, charro-suited Mexican singer named Pedro Infante. Dad was mesmerized! He ran home filled with joy and excitement! “Quiero cantar! Quiero una guitarra!”

For centuries the mountain valleys of northern New Mexico were peppered with small, windowless adobe chapels called moradas. They housed an ancient brotherhood of local Catholic men called Los Hermanos Penitentes. The traditions of penance and chanting alabados during Semana Santa seemed as ancient as the mountains and trees, as old as the acequia that watered animals and fields for food and sustenance. My dad heard their laments in Spanish echo through the trees and mountains near Chacon and Holman in the Mora Valley. They were as much a part of his world as the carne seca de venado or the pungent odors from a freshly butchered hog for a matanza.

Dad loved and respected the Penitentes. But he wanted to be a mariachi! One day, his Tio Flavio surprised him with a guitar made from an old gas can. With a stick for a neck and cat-gut strings tightly spanning the make-shift neck, it was unplayable. Still, having his own guitarra made my dad smile for weeks. He strummed, pretending to be Pedro Infante singing to a beautiful senorita.

When World War II hit like a blast, young men from around the country were thrilled at the thought of thumping Nazis and demolishing fascism in Europe and Japanese imperialism in the Pacific. Dad wanted to go so badly but was too young. He watched as the older boys signed up and went off to fight America’s enemies. His Tio Roberto Lovato had served in the trenches in Europe in The Great War and another primo was sent to fight the Japanese in the Pacific, serving under the command of an actor named Henry Fonda. Dad was too young and too slight to sneak in. Once, he ate five pounds of bananas to try and trick the recruiters into letting him join. His plan unsurprisingly failed.

Dad graduated high school in 1947, then got a job as a clerk-typist in Las Vegas, New Mexico, to help his family in Mora. He had four younger siblings, and there was not a lot of money or food. Then he landed a job at the mental hospital in Las Vegas as an orderly. One day while eating in the commissary, he spied a beautiful, auburn-haired green-eyed young woman and was struck by an arrow of love. She was serving food. He asked her name, but she shyly declined to tell him. Later, he saw her sitting on a bench outside the hospital. He asked again. Ramona Elena Salazar, she said. They talked, went on a date, and eventually married in Las Vegas, New Mexico (not Nevada). They started a family, and as with so many Hispano New Mexicans in the years following the war, joined the diaspora leaving the mountain villages of New Mexico for Denver.

Dad got a job as a civil servant with the federal government. Mom introduced him to her uncle, Jesse Ulibarri, who sang and played guitar. He bought a used guitar and started singing Mexican rancheras, polkas, and waltzes with Uncle Jesse. Soon, they landed a gig at a local downtown bar, dubbing themselves Los Trovadores. Dad quickly bought his first charro suit!

Four kids later, the Martinez family moved south to Albuquerque. Settling in the Northeast Heights, Dad worked by day on the Air Force base, and by night as a mariachi musician. I came along in 1963, about the same time dad founded his band, Los Reyes de Albuquerque. Our home was filled with Mexican music, delicious Mexican food cooked lovingly by our mom, and my older siblings belting out Beatle songs. I remember my dad dressed in dark slacks, white shirt and a tie — his outfit for his day job — then he would change into his mariachi traje, black with silver plata down the side of the pants. He would smile, strum his vihuela, and light up the room. Then he was off to a gig! Dad’s dream of being Pedro Infante finally came true.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

SPACESHIPS, RAY GUNS, AND LIFE LESSONS

By Melinda Snodgrass

“science fiction allows you to discuss difficult and fraught topics in what is a safe space and at arm’s length.”

LITERATURE AS GUIDEPOSTS ON MY IMMIGRANT JOURNEY

By Kei Tsuzuki

“What I have learned from books is that there is no one story that explains the world to us or captures our identity entirely. There is power in the specificity of each of our stories…”

A DIFFERENCE-MAKING BOOK

By Richard Etulain

“Many authors hope their histories, novels or other writings will make a difference — that their works will catch readers’ attention and influence their thinking and actions.”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

ROB MARTINEZ

Rob Martinez is state historian of New Mexico. Before that he was deputy state historian for six years, and also taught high school history at Rio Rancho High School for ten years. Rob was also a research historian for the Sephardic Legacy Project of New Mexico and the Vargas Project at UNM, where he earned an M.A. in history in 1997.