SHARE:

Throughout my life I heard many terms that tried to describe and categorize the Hispano population in the U.S. or those populations considered “brown” — including mestizo, mulatto, Mexican-American, Spanish-American, Chicano, Latino, Hispanic, Hispano/a, or Hispanx. On various official forms, like the U.S. Census or at the doctor’s office, I often saw boxes to check for Puerto Rican, Mexican-American or Chicano. When I told people I was from New Mexico they would ask me if I considered myself Mexican or Spanish. This always confused me … do I really have to pick only one? I am at the same time neither and both. My ancestors came from Spain; they passed through Mexico and undoubtedly, I am most likely related to thousands of distant “cousins” in both places. New Mexico is a land of mestizaje, a mixing and blending of various peoples and cultures. Even though this term comes from the Spanish language and is used locally in our vernacular Spanglish, the actual mixing of cultures took place long before the arrival of the Spanish. New Mexico is not a “tri-cultural” land, as many proudly believe; it is multi-cultural and is unique in that our various cultures have been mixing for thousands of years. I have always wondered as we try to categorize “brown” people, why we New Mexicans have never been considered our own group. I very early began marking those boxes on the forms with a sense of independence and a sense of humor. I would mark the “other” box and then write in the words “New Mexican”? Part of my family has been here in New Mexico for 15 generations; another part came later during the 20th century. It is New Mexican land, water, sky, landscape, food, animals, local customs and the blending of cultures here that make us unique.

Within this context of mestizaje I must add that many Nuevomexicanos discuss how much Spanish, Mexican, or Native American one is. I also grew up with the familiar conversation of who was whose tía abuelo and whose great-grandfather is related to so-and-so’s cousin. The discussion rarely included the “third” party of New Mexico’s tri-cultural myth, the anglo, white or gringo part of our heritage, which is also made up of many different cultures. This was half of my family. How did I fit into this strange mix of New Mexican mestizaje? As a young child I knew that, in addition to whatever Nuevomexicano roots I had, I also had a bit of Scottish and German. Years later my family discovered some Irish. I eventually learned of the historic term for one who is not “entirely” or 100% “brown”… but was part “white” — coyote (koy-yo-tay). Stemming back to the Spanish Colonial era, I learned of this term studying the Mexican Casta paintings (Caste paintings) of the 18th century as well as studying New Mexico history. Although the term may not be PC by today’s standards and is not used that often, at the time it had a somewhat regal sound to me. I think coyotes are magnificent creatures. Later in my career I heard the term used derogatorily by some folks. “Oh that’s right… he/she is coyote…” someone would say with a frown on their face. They had referred to coyote as a negative concept because the person was not 100% Hispano. “What is the problem with that?” I replied. I thought to myself no one is 100% Hispano. What does that even mean? After all, everyone from the Spanish-speaking world is a mix of cultures.

Did being a coyote make me any less New Mexican? What exactly did it mean to be a “Coyota” in New Mexico? Coyote — the wild canine who roams the New Mexican landscape, stereotyped in shop windows on town plazas howling at the moon or whimsically romanticized in Loony Toons comics chasing the roadrunner. I personally view the term as a stronger, more elegant word than the English word used to denote a mixed breed — “mutt”. However, upon pondering this term and its meaning in the dog-breeding world usually the purer the breed, the more chance of a dog being not all that normal due to years of inbreeding. But mutts … mutts made great dogs! My own experiences and upbringing have also shown me that coyotes, or mutts, if one can relate the term to humans, make great New Mexicans! We are the ultimate example of all the goodness that the classic U.S. American melting pot terminology exalts.

Because we were a coyote family in New Mexico, tolerance and acceptance of all people, colors and cultures was the norm. Cultural and racial mixing was so commonplace that the concept of “other” was never even mentioned. On my paternal grandfather’s side we could trace our family roots to 1603 in New Mexico, earlier if going all the way back to Extremadura, Spain. My grandmother, a Navy Wave during World War II, came from Ohio. As the story was told, once the war was over she wanted be as far away from home and her parents as possible, although without going to a big city — to her they were all the same. She ended up in Las Vegas, New Mexico, at Highlands University where, according to my grandfather, she met her “Latin Lover.” After graduating from college my grandparents moved with their first child in tow to Los Angeles where my grandfather completed law school and became a municipal court judge. My parents met at South Pasadena High School. My mother’s wish, like my paternal grandmother’s, was to get away from the smog-ridden environment of late 60s/early 70s Los Angeles. My father enlisted in the Army during the Vietnam War and got stationed in Germany. My mother went with him. I was a honeymoon baby. To this day I still must explain to people why someone with such a classic Latina/Hispana/Spanish/Mexican name was born in Germany. Is it really that weird?

Coyota in New Mexico meant that on my birthday my family would sing the usual “Happy Birthday to you” but that also my grandfather would sing “Las Mañanitas” on my request. Family weddings included La Marcha along with the tossing of the garter and throwing of the bouquet, and funerals often included Penitente hermanos chanting alabados, and on one occasion a funeral included a priest, a rabbi and a Unitarian minister. The holidays were filled with slow-cooked posole, tamales with pork and red chile, and those infamous beef tongue minced meat empanaditas … certainly a direct descendent of a medieval hispano-moresque concoction brought from Spain years ago. We also had my great-grandmother Sprowl’s sugar cookies, the recipe of which I still use today, alongside my great-grandmother Nicolasa’s biscochitos. The finishing touch of any holiday gathering was my grandmother’s extra-large truffle dish with layers of pound cake stacked between red and green colored Jell-O (the other red and green), something we affectionately called “The Thing.” The seasonal playlist included Eydie Gormé and the Trio Los Panchos Alegre Navidad and also the Ray Connif Singers We Wish You a Merry Christmas.

When that one New Mexican stranger used the term “coyote” in a derogatory fashion I realized that being coyote has so much to teach others. It shows tolerance, love and acceptance for multiple peoples and cultures. It appreciates our unique mixed heritage while allowing multiple cultures to exist and thrive side by side. Honoring all of the traditions of my multicultural family indeed has made life richer. This is the New Mexico that I grew up in and where I thrived. My coyote heritage is what makes me proud to be a New Mexican today. I believe New Mexican culture is a unique one that deserves its own box for its people to check off. In the meantime I plan to keep marking off “other” and writing in “New Mexican.” Or else I should write in “coyota nuevomexicana.”

This column was funded in part by a generous grant from the McCune Foundation.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

RUDOLFO ANAYA: CATCHING CULTURES IN BLESS ME, ULTIMA

By Richard Wayne Etulain

Anaya greatly expands the cultural contributions of his novel by combining the usual (Bildungsroman—growing up theme) with the unusual (complex, diverse New Mexico Hispanic culture)…

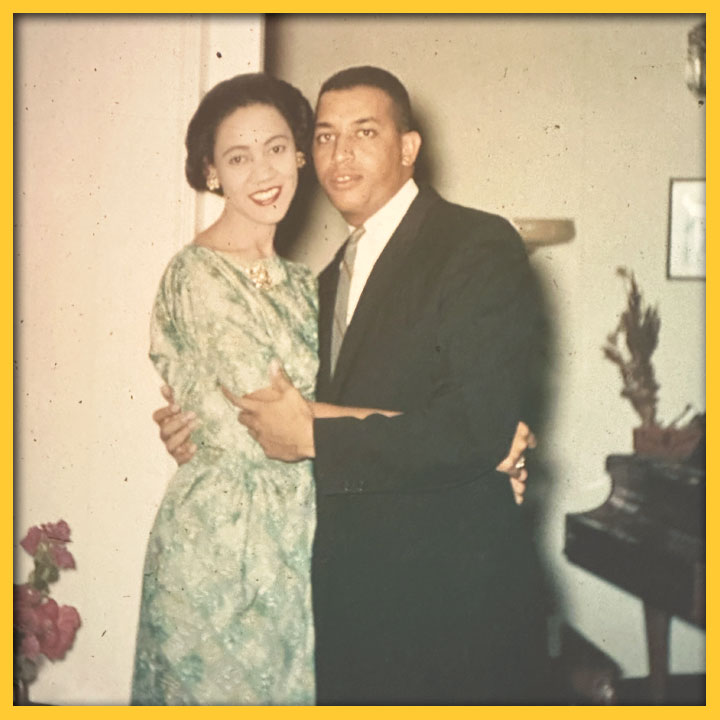

UP BY OUR BOOTSTRAPS; TWO LIVES IN RETROSPECT

By Finnie Coleman

I found myself fascinated with Dr. McIver’s transition from the stultifying hopelessness of the Segregation Era to the wistful hopefulness of the Civil Rights Era…

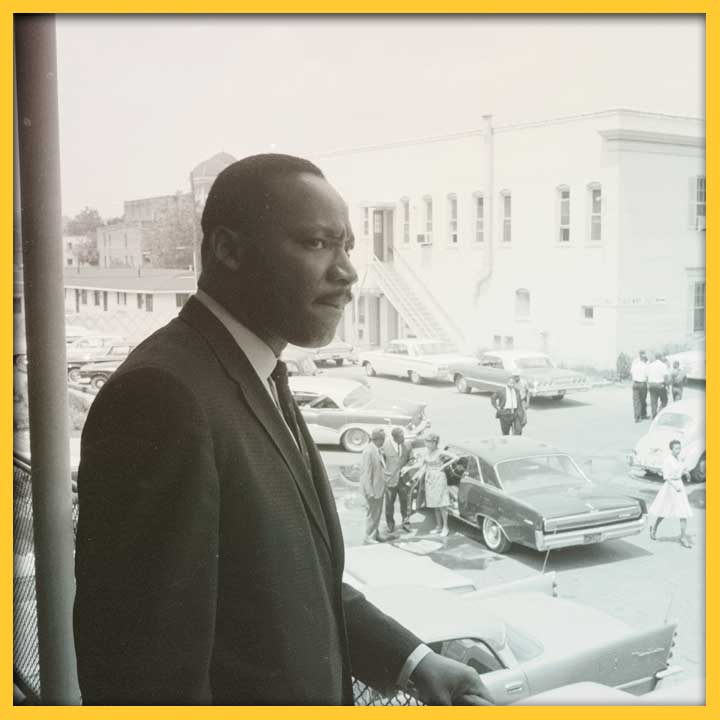

MARTIN L. KING, JR.’S DAMNING LETTER FROM JAIL

By Christopher A. Ulloa Chaves, ED.D.

“In the letter, King used a multi-disciplinary rhetorical approach that applied philosophical, theological, psychological, sociological, political, ethical and economic principles against systemic racism in Alabama…”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

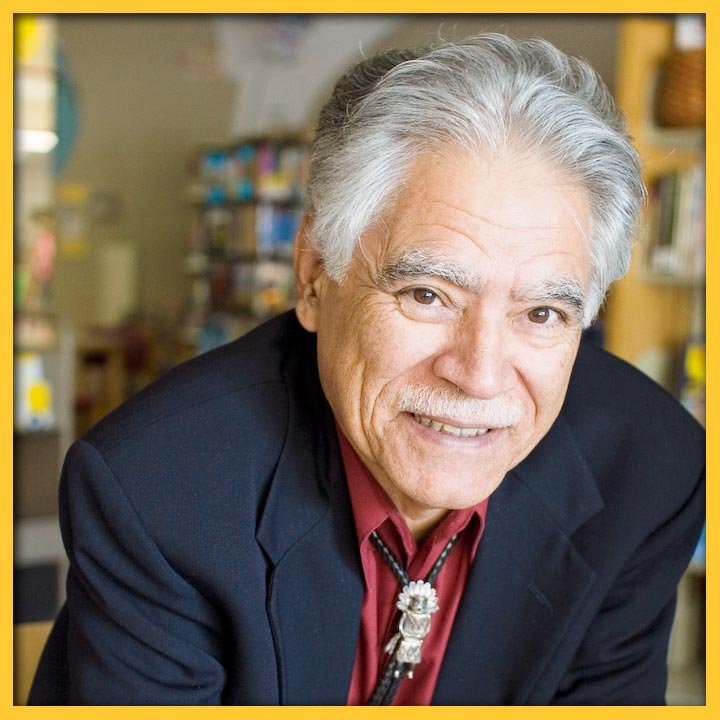

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

NICOLASA CHÁVEZ

Nicolasa Chávez, a fourteenth generation New Mexican, is a historian, curator and performance artist, whose work concentrates on the rich multicultural heritage of New Mexico and the connection between New Mexico and the Spanish speaking world. Her exhibitions include New World Cuisine: the Histories of Chocolate, Mate y Más, The Red that Colored the World, Flamenco: From Spain to New Mexico, and Música Buena: Hispano Folk Music of New Mexico. She was an invited guest curator at the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art in Kanazawa, Japan, for the exhibition Possibility of the Crafts: The Third Triennial of Kogei, which highlighted the traditional arts of New Mexico. She is a contributing author to the publication A Red Like No Other: How Cochineal Colored the World (Skira Rizzoli Press) and the author of The Spirit of Flamenco: From Spain to New Mexico (Museum of New Mexico Press) and A Century of Masters: the NEA National Heritage Fellows of New Mexico (LPD Press) which won a New Mexico Book Award. She performs and conducts lecture/demonstrations on the history of Flamenco, Spanish Dance, and Argentine Tango and currently serves as the Deputy State Historian for our great state of New Mexico.