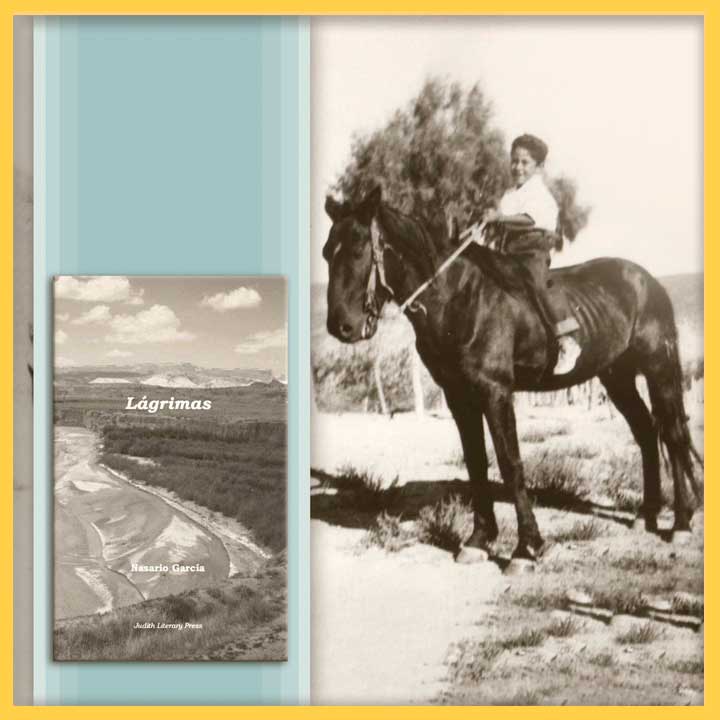

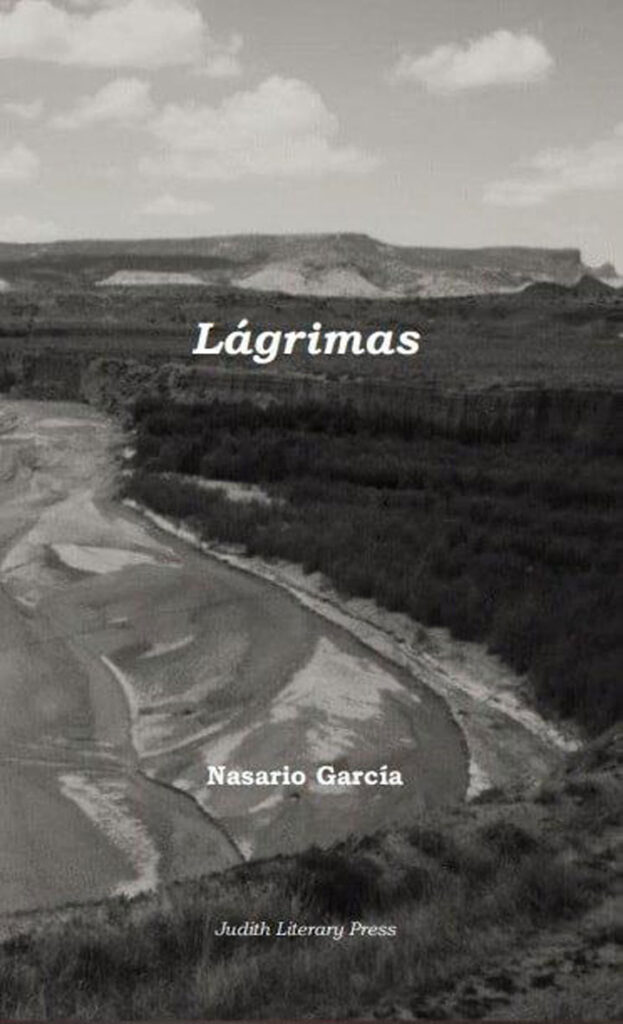

LÁGRIMAS: POEMS OF JOY AND SADNESS

I was fascinated by rural life in the desert where the landscape, the sky, the animals, the birds, and the people brought both happiness and sorrow to my heart, but at the same time each one inveigled my imagination.

PHOTO CAPTION: Nasario García, on horse Prieto in Ojo del Padre, NM. Credit: Nasario ©

SHARE:

Lágrimas: Poems of Joy and Sadness provides an introspective view at how I as a young boy perceived my immediate and extended worlds. Within these two domains rests an array of joyful and somber emotions that take the reader to the Río Puerco Valley southeast of Chaco Canyon where I spent the formative years of my life.

Whether roaming the countryside on horseback, attending fiestas in my village of Ojo del Padre (a.k.a. Guadalupe), or tending to daily ranch chores, each outing was an adventure. In Tiempos lejanos: Poetic Images of the Past, my first book of poetry published in 2004, I wrote the following: “I was fascinated by rural life in the desert where the landscape, the sky, the animals, the birds, and the people brought both happiness and sorrow to my heart, but at the same time each one inveigled my imagination.”

The spirit of these words remains central to my poetry. The poetics may be philosophical, real or imaginary, but they typify my boyhood. While it was customary for children to be seen and not heard, typical in the Hispanic culture, I had the instinct to listen to the viejitos, old-timers, like my grandparents whose words of wisdom piqued my curiosity. I also had the presence of mind to observe the world around me where a hardscrabble farm life was difficult but hardly ever humdrum.

As I wrote Lágrimas, a plethora of poetic images flashed across my eyes. The vivid image in “La cegura/Blindness” of Mamá Juanita, my blind maternal great-grandmother who loved to smoke, remains in my soul. The poem is a tender description, however vicarious, of her world of darkness. I learned to roll and to lite her cigarettes so that she did not burn her delicate and lovely face. Little did I realize that one day in the distant future I would treasure those precious boyhood moments.

On the lighter side, there’s “Zapatos de pastel/Pie Shoes.” Grandpa, a diehard rancher, purchased a pair of new dress shoes. Because of bunions on both feet, he cut slashes on each shoe to accommodate the protruding corns. The cuts resembled fork marks that Mom punctured to the top of her pies before she baked them, but for Grandpa comfort was more important than elegant looks. At night the shoes under his bed looked like two white eyeballs glaring at you in the dark.

The antithesis of the forgoing episodes concerns the local barber in “Señor Copas/Mister Copas.” Señor Copas, as his friends dubbed him, suffered the ultimate humiliation of desaire, rejection at the hands of a beautiful young lady at a community dance. Shunning an elder was deemed disrespectful. The embarrassment coupled with the psychological jolt inflicted on Señor Copas was profound; thereafter whenever he gave his compadres a haircut, he offered them a toast of aguardiente, whiskey, or mula, moonshine. He then sang the sentimental song “Tú sólo tú” as tears streamed down his face.

Beyond people, the landscape and animals were dear to my heart. “Me hablan/They Speak to Me” is a vivid manifestation of how I as a kid communicated with the peaks, valleys, ravines, and arroyos. I spoke and they listened, or so it seemed. At the same time, the vibrant and ever-present wind served as the messenger that carried my bouncing sentiments to and fro. I felt a special kinship and poetic affinity with the topography and tableau of beauty that surrounded me.

A similar feeling existed in my relationship to animals albeit on a more personal basis. Since there was no radio, TV or even books at home, my horses and rabbits occupied a lot of my time. Bayito and Prieto were my steeds’ names, but I also named my rabbits after my cousins Galo, Juan, Julia, and Teodoro. The rabbits, like my saddle horses, enjoyed their own identity.

Lágrimas: Poems of Joy and Sorrow is a poetic mélange of human beings, landscape, sites, and animals. But poetics aside, language and culture are mutually inclusive; one cannot exist without the other. Composing the poems first in Spanish, my native language, some of it from the Colonial Period (1540-1821), merits noting, but the translation to English was equally as important. This is particularly true of culturally charged words or phrases such as “clavarle a uno la uña/to charge one an arm and a leg” or “el baile estuvo padre/the dance was great” that were popular in the Río Puerco Valley. In poetry one must strive to convey spirit and meaning rather than relying on literal transliterations that can be deadly and hackneyed.

The people of the Río Puerco Valley, including my grandparents and my own parents, long ago abandoned their beloved valley. Since then they, like most Río Puercoans, have passed on to a better life. Today most of the old-timers’ adobe homes lie in ruins. Dwellings like my casita have slowly melted into the earth, but what remains alive are the recuerdos, remembrances of a joyful and somber past.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

SPACESHIPS, RAY GUNS, AND LIFE LESSONS

By Melinda Snodgrass

“science fiction allows you to discuss difficult and fraught topics in what is a safe space and at arm’s length.”

LITERATURE AS GUIDEPOSTS ON MY IMMIGRANT JOURNEY

By Kei Tsuzuki

“What I have learned from books is that there is no one story that explains the world to us or captures our identity entirely. There is power in the specificity of each of our stories…”

A DIFFERENCE-MAKING BOOK

By Richard Etulain

“Many authors hope their histories, novels or other writings will make a difference — that their works will catch readers’ attention and influence their thinking and actions.”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

NASARIO GARCÍA

Nasario García, born in Bernalillo, is a folklorist and creative writer (poetry, children's and adults' stories) who has published more than thirty books. He has BA and MA degrees in Spanish and Portuguese from UNM, and was awarded his PH.D. in 19th century Spanish literature from the University of Pittsburgh.