SHARE:

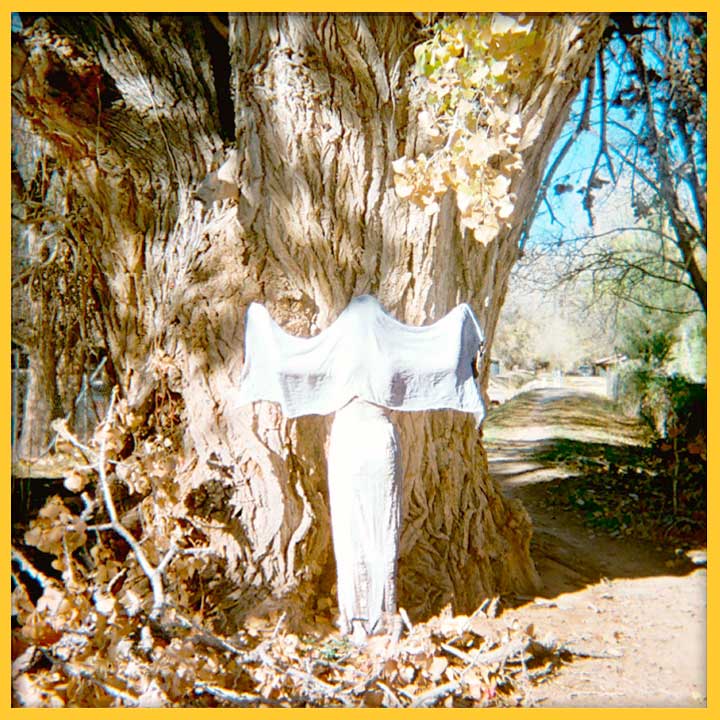

It has always been easy to see myself in the infamous “crying woman,” La Llorona. Like her, I am brown and femme, a survivor of abuse and mental illness, a child forced into adulthood too soon. A consummate Sad Girl™, I carry immense rage with me always and cry often. But rather than dragging me down, my feeling of kinship with La Llorona serves as a daily source of inspiration. A nostalgic tie to childhood, La Llorona was one of the first stories I remember hearing, sitting under the tree in my grandmother’s yard. The tale always fascinated rather than frightened me, and I could not be stopped from retelling it to anyone who would listen. No matter how many parents, friends, and teachers I disturbed with my blithe recounting of the woman who drowned her children, I soldiered on undeterred and unflinching. Clearly, even now I haven’t stopped.

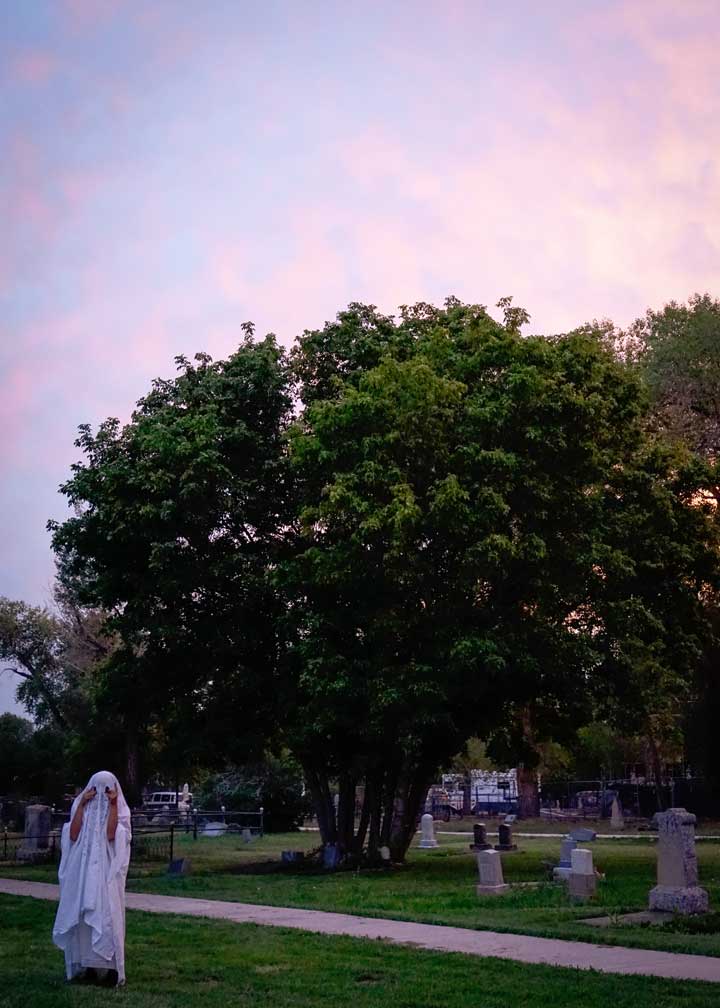

Though many see La Llorona as a monster, a hungry ghost, a killer of children, I saw her as another brown girl, as young as 12 in some tellings, who followed her heart toward the possibility of love and a family of her own construction. Though admittedly, she did not handle it well when her relationship began to crumble, she nevertheless became a misunderstood protectress after death, scaring children away from dangerous bodies of water. It never felt right to me that someone who made poor decisions in the heat of the moment—without the wisdom of age or support of her community—would forever be remembered as a villain. But as I spent more time with her story and its historical context, I began to understand the hatred directed toward her as a kind of large-scale trauma-response rooted in histories of colonization.

There are La Llorona-esque stories nearly everywhere the Spanish colonized, though the myth is most commonly associated with the Americas and the Caribbean. In its most basic form, a woman falls in love with someone who is destined to hurt her because of his high class, Europeanness, or both. Ignoring advice to stay away, she begins a relationship with him and is happy for a time, mothering several of his children. But this man does eventually betray her, either by leaving, discarding her for a wealthier, whiter woman, or in some cases, murdering her and her children. In her sorrow, La Llorona drowns herself and her children, and returns as a ghost to haunt waterways searching for her family. Expressing a deep-rooted anxiety about the fragile nature of love, life, and family, La Llorona’s tale warns of the dangers inherent in crossing race or class boundaries in colonial contexts.

Though some might say the moral of the La Llorona story is to listen to the advice of your community, to me the story has always said more about the lack of accountability for her partner, and more broadly, for people in power. While La Llorona loses everything in her attempt to build a family with someone she loved, her former lover is insulated by his wealth, whiteness, and masculinity, and remains unaffected by their breakup. Though his actions directly precipitate the violent deaths of his own children, he slips effortlessly out of the story and is not held responsible for leaving La Llorona and her children vulnerable. The blame instead falls on La Llorona alone, whose rejection by her lover and community is compounded by that of contemporary storytellers.

This ongoing storied rejection is one of the many features that ties La Llorona’s narrative to that of the real historical figure of La Malinche, the Nahua translator for Hernán Cortés. Mother of some of the first mestizos, La Malinche is remembered as a traitor, evidenced by the term malinchismo, which describes a feminine form of treachery[1] or a preference for European over pre-Columbian people or culture.[2] However, her fuller history complicates this oversimplification. Sold into slavery by her family, La Malinche was not yet a teenager when she was given to Cortés as a sex slave, and barely an adult when he forced her to marry another conquistador. Rejected by her family, then Cortés, then her people, she fled to Spain with her children, where she converted to Christianity to survive. While she undoubtedly bears some responsibility for Spanish conquest in Latin America, what La Malinche (and La Llorona by extension) actually betrays is our collective failure to protect our most vulnerable from exploitation.

Given this reading, I think the hatred directed toward La Llorona more likely comes from what Audre Lorde describes as the “unrelenting sharpness reserved only for each other.”[3] In other words, when we see ourselves reflected in the vulnerability or imperfection of another, we often to reject them out of a misguided attempt to protect ourselves. La Llorona and La Malinche’s tales highlight cultural anxieties over where we—members of the mestizaje—come from, who will love us, and how we will live with the violence in our family trees. We do not hate La Llorona and La Malinche because they are evil, we fear them because we feel their pain.

Earlier in this essay, I said I was inspired by La Llorona and it’s true. Despite the heaviness, sorrow, and injustice of her story and those that inform it, her enduring presence in the cultural zeitgeist underscores how necessary chaotic brown femininity is to the formation of the Latinx identity. Think about it: Despite centuries of murderous campaigns to center European worldviews in the Americas, our traviesa foremothers remain at center stage. Hell, even la Virgen de Guadalupe comes from Our Lady of the Apocalypse, hinting at la raza’s uncanny ability to survive rejection, isolation, and genocide. So, what if we embraced the scrappy complexity of figures like La Llorona instead of rejecting them? Perhaps then we could find love for the unpredictability she reflects in ourselves and others. Perhaps then we could overthrow the generational curses that haunt us.

[1] Ramírez Catherine S. “A Genealogy of Vendidas.” The Woman in the Zoot Suit Gender, Nationalism, and the Cultural Politics of Memory, Duke University Press, Durham, 2010, p. 23.

[2] González Díaz, Marcos. “‘El Malinchismo Es Una Enfermedad Social De Los Mexicanos Ligada a Un Complejo De Inferioridad Hacia Lo Extranjero.’” BBC News Mundo, BBC, 3 Sept. 2021.

[3] Lorde, Audre. “Eye to Eye: Back Women, Hatred, and Anger.” Sister Outsider, Penguin Books, New York, NY, 2020, p. 156.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

SPACESHIPS, RAY GUNS, AND LIFE LESSONS

By Melinda Snodgrass

“science fiction allows you to discuss difficult and fraught topics in what is a safe space and at arm’s length.”

LITERATURE AS GUIDEPOSTS ON MY IMMIGRANT JOURNEY

By Kei Tsuzuki

“What I have learned from books is that there is no one story that explains the world to us or captures our identity entirely. There is power in the specificity of each of our stories…”

A DIFFERENCE-MAKING BOOK

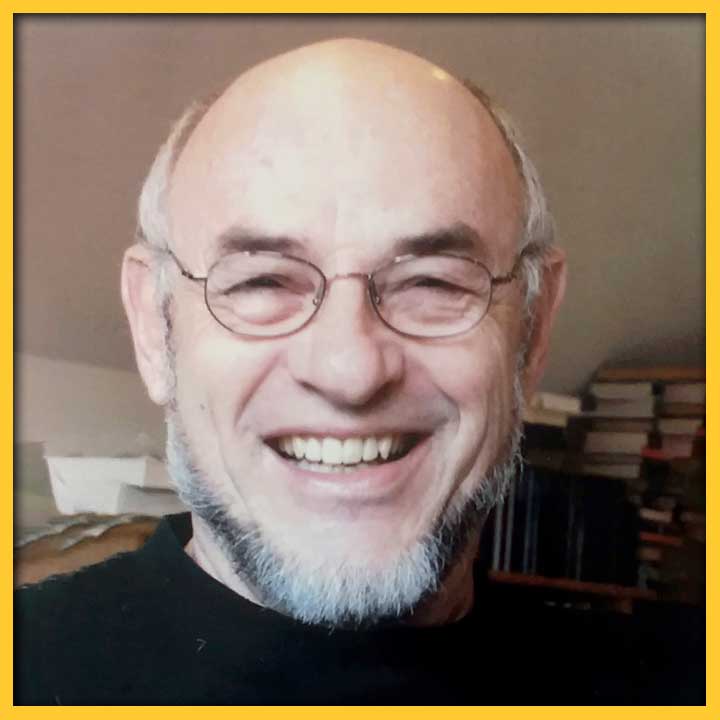

By Richard Etulain

“Many authors hope their histories, novels or other writings will make a difference — that their works will catch readers’ attention and influence their thinking and actions.”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

RICA MAESTAS

Rica Maestas is a burqueña artist, author, and cultural worker interested in vulnerability, whimsical connections, folklore, mutuality, and ritual. She has received numerous grants for her creative work, curated independent, experimental exhibitions as well as institutional projects, published writing in diverse forums, and exhibited visual art and performance pieces nationwide. A 2022 Labor Resident artist at the Santa Fe Art Institute, she holds a MA in public humanities from Brown University, manages digital storytelling and membership engagement at SITE Santa Fe, lives in an adobe with her family of fire signs.