MANITO

Manito: Examining and Deconstructing New Mexico’s Tri-Cultural Myth; ‘Patterns of Migration.’ Mama’s easy, un-flinching and quick-to-respond reply to this unfamiliar term, word, name, was curious to me. Manito.

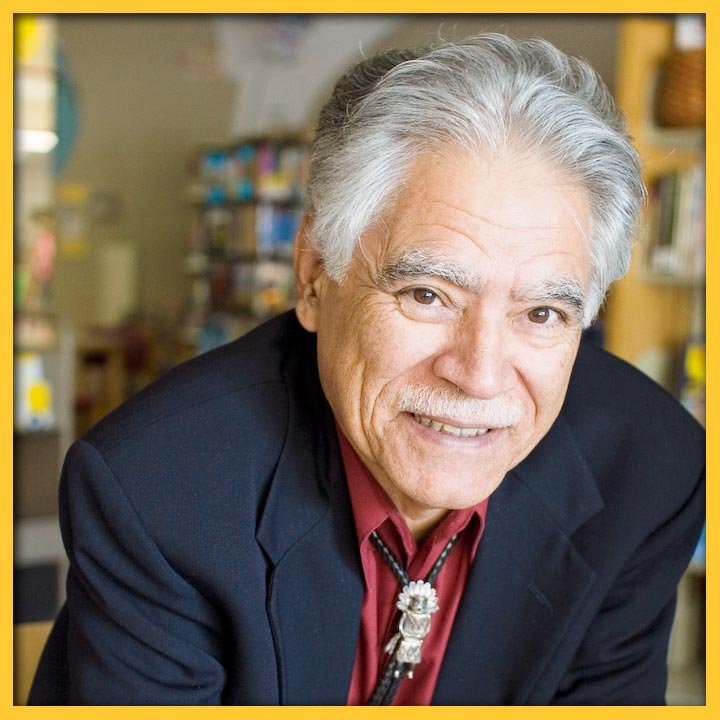

PHOTO CAPTION: Leonard Martinez, 1942, age 27. Photo courtesy of Leonard Martinez, photo by L. Torres.

SHARE:

Growing up, I’d never actually heard Mama use the title “manito” but when I mentioned the word out-loud one afternoon, Mama easily, almost on-cue, replied with “yeah, my Daddy was a manito…”

I’d read the word – manito – in the recently published anthology “Querencia; Reflections on the New Mexico Homeland” (2020, UNM Press), where one of the editors & author, Levi Romero, describes the word as “a derivative of the word ‘hermanito’…a term of endearment”, and a term applied by Mexican immigrants to New Mexican Hispanics.

Mama’s easy, un-flinching and quick-to-respond reply to this unfamiliar term, word, name, was curious to me. Manito.

Why hadn’t Mama ever revealed, or used this word before? Again, her response was so quick, as honest as a reflex, and yet she’d never told me origins of its story, nor what it meant to our familia. And I thought too of all the things my Mama rarely said, but kept to herself, hidden in the depths of herself, yet to be revealed.

Manito. And of all the estorias about my Papacito, this was one I’d “known” about him, and yet remained un-named/un-defined – until now.

A rare, but favorite photograph of my Papacito is hung on my home-office wall, “printed” on a 5×7 wood-block. In the picture he is standing straight and serious, both arms hanging at his sides (as though prompted by the photographer to just stand there, no pose in mind). His hands are not in his pockets, but at his sides. His expression is “serio”, no emotion in his expression whatsoever. I imagine the photographer, another man, urging him to smile, and Papacito ignoring this request. Instead, his face is captured nearly expressionless – that is – until you look closely. His eyes are unapologetic, un-interrupted despite the various tragedies he endured in life. All his life reflected in his eyes.

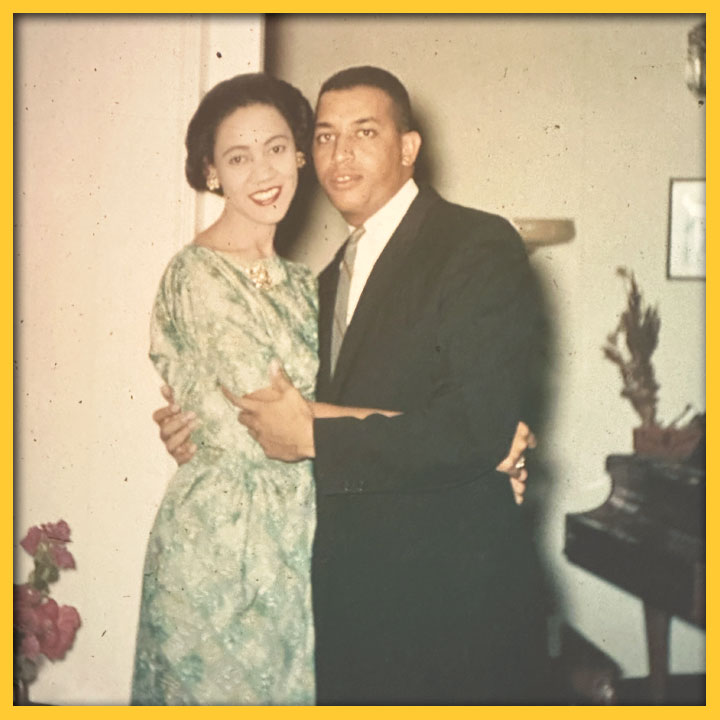

Abandoned by his own father as a young boy (left at a gas-station at the age of 12), my Papacito made his way from his tierra of Peñasco NM, further north, following labor and wanderings until he ended up in Wyoming, rooming there with other familiar manitos and family. There he eventually also found a wife (married my Mamacita when she was only 16, he 27), and raised a small family of three in the town of Rawlins Wyoming. Papacito died in Wyoming, but Mama describes him in his later years, especially after his cancer diagnosis, wanting desperately to move back to his tierra, his home, his origins – Nuevo Mexico.

I think of the small intricacies of my Martinez-family-roots – the un-spoken, un-explored particulars that challenge the tri-cultural myth within NM families themselves – those elements that deconstruct the idea that all NM-rooted Hispanics are the same, of shattering the stereo-types of our gente, of acknowledging that there are mixtures and differences, and each family has its own distinct storyline that traces and threads through many origins. Storylines cross threads, a migration of both the physical and the social, not defining us as much as creating what we will become.

Papacito was a manito, but was never able to move back to NM before he died. However, his daughter (my Mama), did in fact migrate back to the homeland. In fact, if I relay this story honesty, the truth is that Mama got the hell out of Wyoming as fast as she could. And while much of her immediate family remains – two brothers, nieces and nephews, primos y primas – Mama herself migrated back home, to the land of her “Daddy”, eager to escape the deep and brutal racism she experienced in the town of her childhood, Rawlins Wyoming.

Something deep called Mama back to her father’s homelands of Nuevo Mexico, and she’s lived here ever since. Perhaps something subconscious deconstructed and challenged the tri-cultural myth for Mama herself, and perhaps it continues today? Mama’s migration back to her father’s manito homeland was complete when she earned her Master’s degree from Highlands University, married a Hispanic-man also from NM, and raised two children who would and could speak both English and “New-Mexican” dialect Spanish. My Mama migrated back to the homeland of her father, and lives here still, proudly, and contently. It is her migration.

Mama has always referred to her father with the endearing term “Daddy”, and while I was never able to meet him, Mama has always relayed the story of how proud he was when I was only a year-old, waddling around, already “speaking” the Spanish words Mama was teaching. To this day, my brother and I remain the only grandchildren of Papacito’s lineage that still speak Spanish and reside in his homeland. This fact remains un-spoken, never mentioned among the Wyoming-primos, but it is something I know Mama carries with pride.

If I continue exploring the small intricacies of my Martinez-family-roots, the particulars of a culture’s migration, I see – Tio Max treasuring and often listening to Tio Don’s and Nina’s old Spanish records; my prima Tina replying via text regarding my question about how her new grand-daughter is doing, her text back relaying “…My beautiful hijita!” when referring to her dark-eyed-dark-haired grandbaby; the fact that Tia Mae still makes one of the best damn green-chilie-stew’s I’ve ever had. These family members do not reside in Nuevo Mexico, and yet the traditions continue, expand, cultivate, evolve.

Papacito was a manito de Nuevo Mexico – it’s meaning with deep northern New Mexico traditions, language, mannerisms, musica, querencias still live as a part of his familia’s daily life. This too is a migration – the migration of traditions of daily life from one generation to another, despite geography, despite what State of the Union our familias reside.

Mama’s gift to her two children: teaching us the language, the customs, the foods, the joy’s of her father’s Nuevo Mexico.

The manito migration of my Papacito lives on, and I too will pass it on. Con amor, con querencia, con gusto, y con bendicíon…

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

RUDOLFO ANAYA: CATCHING CULTURES IN BLESS ME, ULTIMA

By Richard Wayne Etulain

Anaya greatly expands the cultural contributions of his novel by combining the usual (Bildungsroman—growing up theme) with the unusual (complex, diverse New Mexico Hispanic culture)…

UP BY OUR BOOTSTRAPS; TWO LIVES IN RETROSPECT

By Finnie Coleman

I found myself fascinated with Dr. McIver’s transition from the stultifying hopelessness of the Segregation Era to the wistful hopefulness of the Civil Rights Era…

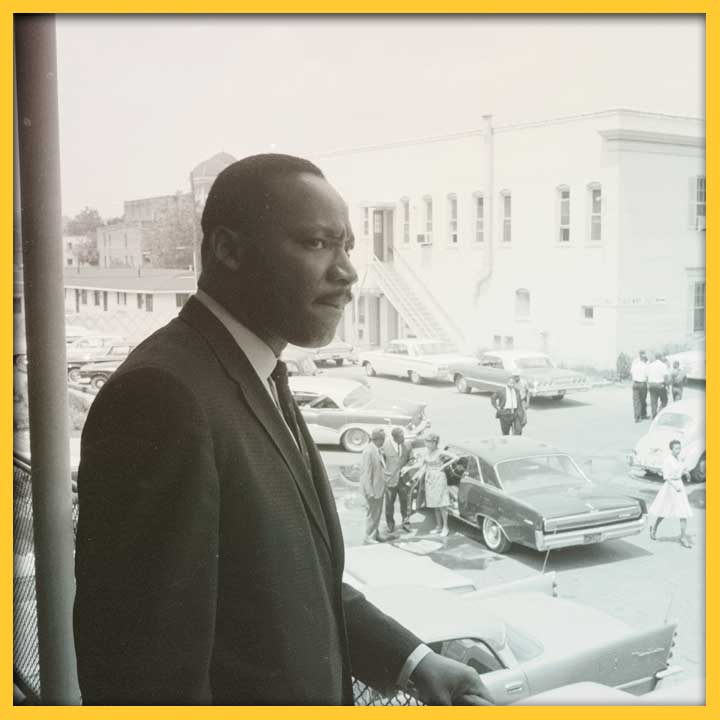

MARTIN L. KING, JR.’S DAMNING LETTER FROM JAIL

By Christopher A. Ulloa Chaves, ED.D.

“In the letter, King used a multi-disciplinary rhetorical approach that applied philosophical, theological, psychological, sociological, political, ethical and economic principles against systemic racism in Alabama…”

SHARE:

This column was funded in part by a generous grant from the McCune Foundation.

EXAMINING AND DECONSTRUCTING NEW MEXICO'S TRI-CULTURAL MYTH:

Submissions related to this special initiative may deal with understanding of past and contemporary issues of race relations; patterns of migration; diverse voices that have emerged in New Mexico, and challenges to the widespread public belief that New Mexico’s history and cultural heritage consists of only three ethnic groups: Native, Hispano and Anglo.

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Leeanna Teresa Martinez y Torres

L.T. Torres is a native daughter of the American Southwest, with deep Indo-Hispanic roots in New Mexico. She has worked as an environmental professional throughout the West since 2001. Her creative non-fiction work has been published in Blue Mesa Review, Tupelo Quarterly, and is forthcoming in an anthology by Torrey House Press (2021).