PRE-PANDEMIC GRIEF, ANCESTRAL MEMORY, MOURNING THE WORLD IN 2020 AND HEALING IN THE PRESENT

I now find myself dwelling upon ancestral homelands of my Diné (Navajo) matriarchs and male patriarchs in the San Juan Valley and at Herfano, N.M.

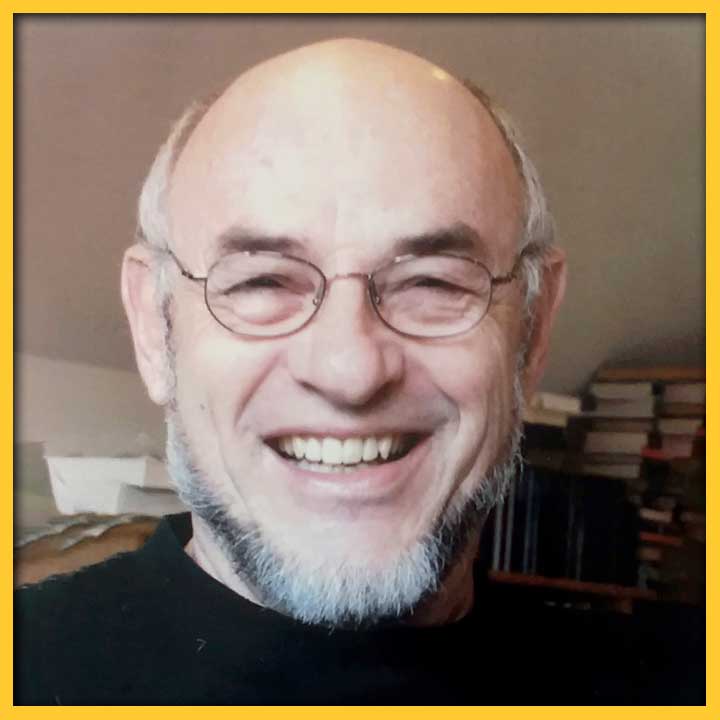

IMAGE: Dressed in her matriarch garments, Venaya’s late maternal grandmother Jane Werito Yazzie sits in her childhood home at Dziłnaodiłthe (Huerfano) N.M. on the eastern region of Navajo land.

SHARE:

here

desert girl emerged –

she

stumbled

on to surface chaos

where – rain bowed

earthdwellers

pouredpowdered turquoise

on to

ant hills…

My late maternal grandmother Jane Werito Yazzie and grandfather Alfred Padilla Yazzie Sr. raised me. It is from their dialogue and cultural narrative that I now carry inherited resilience, artistry and compassion as an adult being in 2023.

Shimá, (my grandmother) would tell me that as a young child I would suddenly just begin crying out of the blue — though I wasn’t hurt or in any physical pain when these crying moments would happen. Eventually my sudden outbursts of tears and emotions were accepted and became a natural occurrence. Looking back at my childhood history I believe that this behavior was (and still is) a high sensitivity to the spiritual realm. But, more specifically I think it has much to do with what the late Indigenous philosopher Jo

hn Trudell referred to as “inherited generational trauma.” He stated concerning this concept that, “It’s like there is this predator energy on this planet, and this predator energy feeds on the essence of the spirit.” In his philosophies he spoke about how we as Indigenous peoples carry in our genetic DNA the memory of our tribal ancestral past, which included and still includes a plethora of spiritual and physical violence and trauma. So, I ask, was my open weeping and emotional state of distress as a child my own experience of genetic memory of my vast Diné people’s historical past? I often ponder upon this personal history of my childhood; my own personal sense is that the trauma of my ancestral past was and is embedded deep within my being, and so I mourned. This personal history is relevant because it’s linked to global events that transpired in 2020, a time when all humanity mourned as the great sickness spread around us.

…in the west

songs surged from mouths of

the

glistening earth dwellers

in unison their almond-shaped mouths murmured,

Sho

Sho Sho

Sho…

here

in early cover of stars,

desert girl- wearing ochre-hued earth shoes

on her calloused feet…

I now find myself dwelling upon ancestral homelands of my Diné (Navajo) matriarchs and male patriarchs in the San Juan Valley and at Huerfano, N.M., in the northwest region of the state. I am a resident of a small industrial and farming community that was named “Farmington” by early Euro-American Anglo settlers. But there exists a more beauty-full and ‘living’ expression about this place located between the Animas and San Juan rivers. Tótá is what my Diné people call this cultural landscape — rich

with sandstone, cottonwood forests and abundant green high desert sage, an environment I am blessed to call my ancestral homelands. Tótá is ‘the place of water,’ and water is therefore a healing element in the Indigenous spiritual epistemologies. Many Four Corners Indigenous people hold the rivers in high esteem including: the Ute Mountain Ute, Southern Ute, Jicarilla Apache, Pueblo groups and the Diné people. Besides being a “border town” Tótá is a land narrative and Indigenous cultural history that heals the spirit and soul. Land tells of the past and present Indigenous presence upon the land; sacred narrative passed on to me by my Diné people and Shimá.

…here

she emerged.

…stumbled

on to surface chaos

where –

under blue veins of eyelids,

desert girl’s story

flooded brown dirt:

in 1972 she was bundled in yucca roots.

in 1972 she was presented to the two-legged earth dwellers.

In 1972 she was present in a border town.

brown desert daughter –

spirit bare as river cobbles, murmured,

Sho

ShoSho…

Three years have passed since Shimá left this place, and I have carried my grief in the blue bird satchel on my right hip; an homage. Shimá was my light; her dialogue shone upon my path and with her by my side I was whole. I think of her daily, how she laughed and the ways in which she told the story; this is my source of love. My grandmother’s death occurred in February of 2020, before the Covid-Monster appeared in the American Southwest. As I was mourning her, the global sickness arrived to humanity; we collaboratively became prey to an invisible entity— just as in the ancient Diné stories, we were in essence fleeing and hiding from the giant monsters that roamed the land again. It is no doubt that we were humbled to the core. What did we learn from this disharmony? How did we survive in the intangible sense?

Our loved ones were taken from us, and the Monster kept us hidden away to deal with our individual loss and grief. Some tackled grief with a warrior spirit, some carried fear in a backpack upon our shoulders, while others gained and shared strength through the humanness of faith and prayer. This moment in our history affected us mentally, spiritually and physically, for we are not the same beings we were before 2020. There is no doubt that the pandemic changed us, but what did we take away from such an experience? Did we change how we lived? Do we still care? Do we love our family even more? Did we reform from bad habits? Do we currently live a life that is grateful for survival? Or did we just go back to our old habits, living without real compassion and empathy for our world? Do we now consider and or acknowledge the land as a healing element?

During the time of loss, fear and grief I turned to my omnipresent Creator and ancestral homelands for guidance and healing. And I still do.

…dewy with haze of morning migration

desert girl

witness to grief of the five-fingered earth dwellers,

she stands in resilience at the foot of Shiprock, the rock with wings.

early dawn

spoke

herworld

into

existence.

desert girl’s Masaní doo bi Chéí filled her sight.

in 1972 the new Life before them

like rain flooding their desert floor,

they murmured:

Sho

shidiyiin God t’aa’ayisí áhéhé

é.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

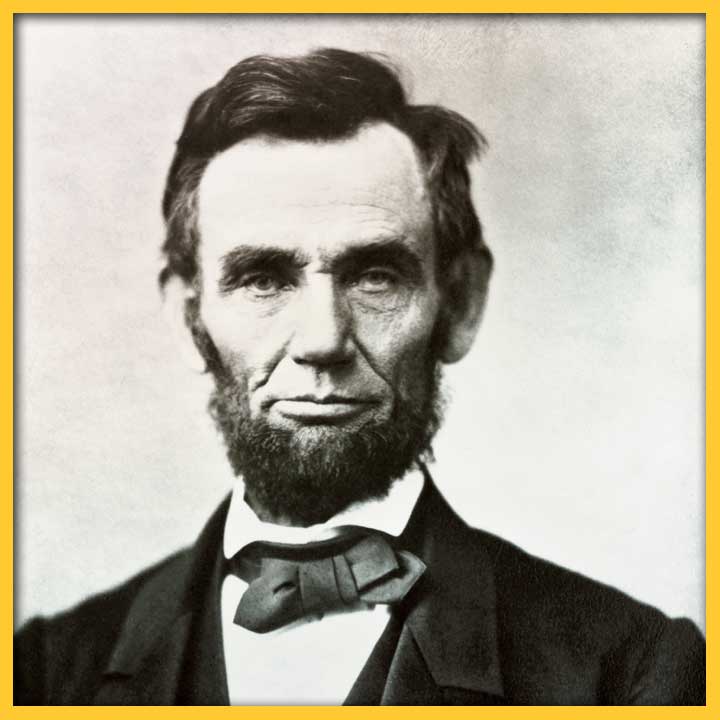

A DIFFERENCE-MAKING BOOK

By Richard Etulain

“Many authors hope their histories, novels or other writings will make a difference — that their works will catch readers’ attention and influence their thinking and actions.”

CELEBRATE CONSTITUTION AND CITIZENSHIP DAY EVERY DAY, NOT JUST SEPT. 17TH

By Maryam Ahranjani

“As a teacher and mother and child of immigrants who now teaches Constitutional Rights to law students, this day is always a special one for me.”

THE THIRTEENTH AMENDMENT THAT NEVER WAS

By Brandon Johnson

The 13th Amendment, guaranteeing the abolition of chattel slavery in the United States, is one of the crown jewels of the American Constitution.

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

VENAYA YAZZIE

Venaya Yazzie is a Diné|Hopi multi-disciplinary artist and poet from the eastern region of the Navajo nation. She resides in Tóta, NM between the San Juan Animas rivers. Visit Venaya's work here: https://www.opendoorsartinaction.com/venaya-yazzie.