REFLECTIONS ON THE BLACK FOOTPRINT IN NEW MEXICO

Let’s begin with a story that reflects my concerns that the Black presence isn’t significantly appreciated — but that simultaneously reaffirms my belief in the importance of teaching New Mexican Black history.

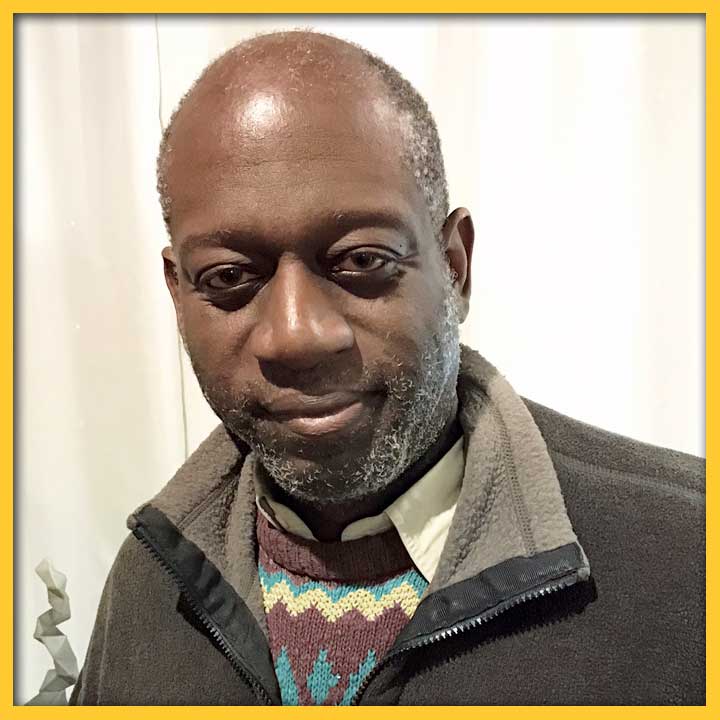

IMAGE: Author, poet and blog contributor, Darryl Lorenzo Wellington.

SHARE:

Let’s begin with a story that reflects my concerns that the Black presence isn’t significantly appreciated – but that simultaneously reaffirms my belief in the importance of teaching New Mexican Black history.

Not long ago, I sat in a café reading a copy of Dennis Herrick’s excellent 2018 historical biography Esteban: The African Slave who Explored America. A woman who had been a poetry student of mine saw the title, was startled and pointed, saying “Oh, him? I heard he was terrible. A terrible womanizer, and a greedy, lowdown dog.” Heavy emphasis on dog.

Who was Esteban? (It’s an answer which you should know if you don’t already, but… )

A Black slave, he was born in sub-Saharan Africa, enslaved in Morocco, and in 1527 he accompanied his Spanish master on an early expedition to the New World; he became the first explorer to lead a party that arrived in Zuni lands.

In the words of the Puebloan author Joe S. Sando: “The first white man our people saw was a Black man.”

It is nothing short of uncanny that a Black African became the leader of this expedition. I lack the space to relate the whole narrative (please look it up) so let me just say that from 1527 to 1536, Esteban traveled in the regions we now call Florida, Texas and Mexico. Unlike the Spaniards, whom he accompanied, he made many significant contacts and fellowships among Native peoples. He was the only member of his Spanish party to learn tribal languages, even becoming fluent. On a subsequent 1539 expedition, he led a group of approximately 100 Mexican Natives who reached what is now the U.S. Southwest, and made contact with the Zuni village of Hawikuh. Thereafter Esteban disappeared.

Which means? The most often-repeated narrative is that Esteban — who previously appeared to have been a skilled communicator with Native peoples — suddenly grew arrogant and demanded that the Zunis supply him with women and gold. The offended Zunis then killed him. Dennis Herrick points out that this narrative, which has been handed down from Spanish conquistadors, is highly dubious. Francisco Coronado, who first penned it, needed to explain Esteban’s mysterious disappearance. He told his superiors Esteban was killed “because he was touching their women” while ironically claiming he himself was a Christian “who did not kill anyone’s women, but Esteban did kill them.”

The last claim is “a whopper” writes historian Dennis Herrick. “Coronado wrote that self-serving propaganda a few weeks after he had ordered the executions of Indian women. And Spaniards as well as other Europeans had been killing thousands of women and children for decades in the Caribbean and the Americas. Coronado‘s letter is a good example of how conquistadors would lie” on official records.

There is another story passed down by the Zuni Indians. They say they may have engaged in a battle with Esteban, but they captured him alive. After holding him for three days, they came to an agreement and evidently “worked things out.” They let him go unharmed. To where? Did Esteban (as has been speculated) flee into Mexico, join other tribes, and escape from slavery? This version of Esteban’s fate shifts the narrative towards being a Black liberation story.

No one truly knows what happened — since Esteban never communicated with the Zunis, or the Spaniards again. But my point is that the liberation narrative is slightly more credible, yet is rarely told. And the Spanish version is obviously tainted by racial bias. Coronado’s letter smacks of an urgent need to demean the accomplishments of a Black slave, who subsequent generations labeled “a dog.” Yet he was an extraordinary individual. Esteban’s arrival preceded thousands of Black slaves who the Spanish brought later. His presence — like theirs — establishes beyond a hint of doubt that we have always had a footprint here. To Blacks today, this is a definition of belonging.

Esteban is a meaningful precursor in another way — his brilliant individuality. New Mexico’s wide spaces have attracted many African American individualists, eccentrics, and dreamers who relocated to escape harsh Jim Crow laws in Texas.

Many survived under awkward circumstances. They include former slaves and Buffalo soldiers stationed in New Mexico forts, or the founders of Blackdom, an ambitious, entrepreneurial all-Black community founded near Roswell in the early 20th century.

Another Black New Mexican individualist was George McJunkin. Born into slavery in 1851, following Emancipation, McJunkin taught himself to read and relocated from Texas to New Mexico, believing this was a land of opportunity. McJunkin became a very successful rancher. His career would have been noteworthy for this alone. McJunkin was also an amateur naturalist. In 1907, he discovered a cache of bones, near Folsom, N.M., which he knew were prehistoric. Like Esteban, McJunkin faced skepticism and racism. Though he knew his discovery was significant, he labored until he died in 1922, trying to interest professional archeologists.

When the Folsom site was finally excavated, the discoveries revolutionized the study of man. Previous archeologists believed that indigenous people occupied North America only for a short span of time. The site contained artifacts over 10,000 years old, scientifically confirming that indigenous people have been here since time immemorial. The site confirmed what Indigenous people already said — that they had been here since prehistory.

The Black presence in New Mexico is a trajectory, but not a separate history. George McJunkin’s example provides a case in point. He is a Black hero who confronted anti-Black racism, but his legacy is interwoven with other New Mexico cultures. His legacy enhanced our ability to relate to each other, honoring the tapestry of the Land of Enchantment.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

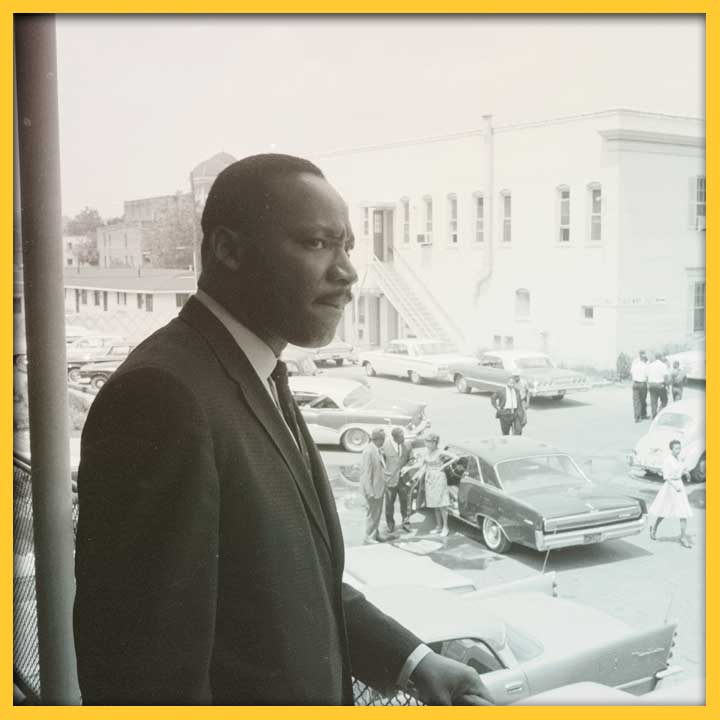

MARTIN L. KING, JR.’S DAMNING LETTER FROM JAIL

By Christopher A. Ulloa Chaves, ED.D.

“In the letter, King used a multi-disciplinary rhetorical approach that applied philosophical, theological, psychological, sociological, political, ethical and economic principles against systemic racism in Alabama…”

SPACESHIPS, RAY GUNS, AND LIFE LESSONS

By Melinda Snodgrass

“science fiction allows you to discuss difficult and fraught topics in what is a safe space and at arm’s length.”

LITERATURE AS GUIDEPOSTS ON MY IMMIGRANT JOURNEY

By Kei Tsuzuki

“What I have learned from books is that there is no one story that explains the world to us or captures our identity entirely. There is power in the specificity of each of our stories…”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

DARRYL WELLINGTON

Darryl Lorenzo Wellington is 2021-2023 Poet Laureate of Santa Fe, N.M. He is also a speaker/presenter in Speakers Bureau program, who lectures on Black poetry.