SHARE:

More has been written about Billy the Kid than any other New Mexican. He also rivals Jesse James and General George Custer as the most-written-about figure of the Old West. And dozens of books and essays flood out each year, and, most often, they tell changing stories about the Kid. Why should this be? What should these shifts tell us?

We should think about storytelling — why some characters and stories are so popular and others not. In addition, we should ponder why these stories often shift in their points of view about historical figures and their lives. What do transitions in some tales tell us about the heroes, heroines, and villains of those yarns, and do those changes in character interpretations reveal anything about changing times? Looking at the content of the most popular stories and how the tales have changed over time, as well as at those telling the stories, we can think more intuitively about ourselves and the subjects that intrigue us.

The popularity of Billy the Kid and the stories about him is one way of thinking about New Mexican and Western stories and their multiple meanings. In the first years after Pat Garrett shot Billy in 1881, most depictions of Billy were negative, portraying him as a thief and killer who murdered 21 men, one for each year of his life. In the 1920s, opinions shifted with both books and movies more likely depicting Billy as a guy to ride the river with, as a joyous and adventurous young man. Then, toward the end of the 20th century, biographers and historians began to describe the Kid as a more complicated figure, displaying both positive and negative features. In the 21st century most life stories of Señor Billy have followed this Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde complex approach.

The transitions in interpretations of Billy the Kid illustrate a truism in storytelling: When the thoughts and conclusions of the present day shift away from previous points of view those shifts usually lead to changing views of the past. When Americans became more sympathetic to Native Americans beginning in the1960s, interpretations of historical Indians became more positive. When new roles for women emerged at much the same time — also in the `60s — views of women’s roles in earlier American history became fuller and more empathetic. A new present almost always leads to new kinds of pasts.

Put another way, story-catching — hearing information for the first time about a subject or a new view of a familiar topic — frequently leads to new kinds of storytelling about the past. Stated succinctly, when biographers and historians heard previously unknown or overlooked stories about Billy the Kid’s warm friendships with Hispanics and his closeness to his mother and adult women in Silver City, New Mexico, they “caught” those stories and produced more balanced — and complex — narratives about the Kid. Yes, he stole cattle and horses and was involved in the assassination of a Lincoln town sheriff and in other shootings, but alongside those nefarious actions were his joyous friendships with Hispanics and warm relations with adult women.

What has happened in interpretations of Billy the Kid should awaken us to important thoughts about storytelling. Realize that interpretations of the past rarely remain the same forever. Notice, too, that shifts in present-day opinions frequently lead to changes in views of the past. Understand, also, that these shifts are ongoing, because subsequent generations will continually experience new ideas and actions, leading to ongoing reinterpretations of the past.

Finally, story-catching — hearing and understanding the present — will help perceptive students realize why interpretations of the past, as with the present, are almost always in continual flux. The many changing narratives about Billy the Kid can — and should — be a valuable lesson about storytelling.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

RUDOLFO ANAYA: CATCHING CULTURES IN BLESS ME, ULTIMA

By Richard Wayne Etulain

Anaya greatly expands the cultural contributions of his novel by combining the usual (Bildungsroman—growing up theme) with the unusual (complex, diverse New Mexico Hispanic culture)…

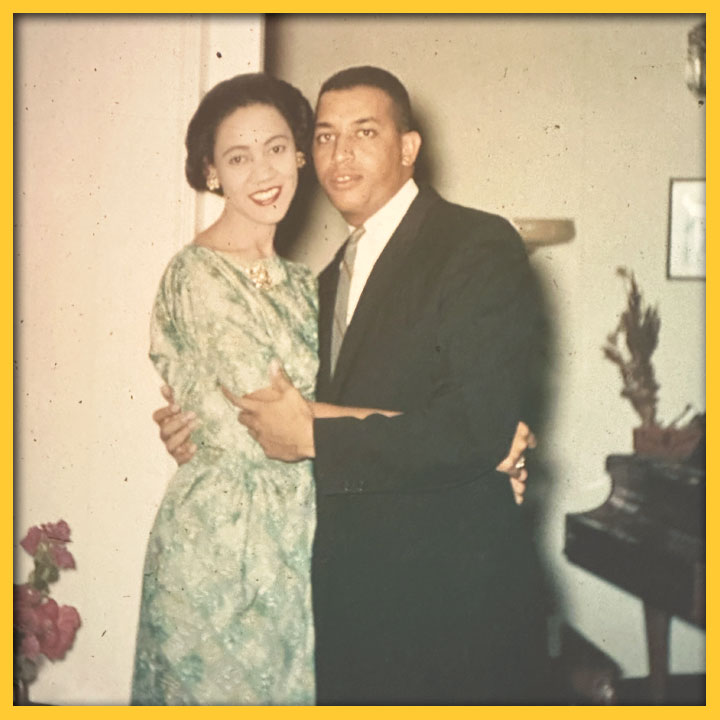

UP BY OUR BOOTSTRAPS; TWO LIVES IN RETROSPECT

By Finnie Coleman

I found myself fascinated with Dr. McIver’s transition from the stultifying hopelessness of the Segregation Era to the wistful hopefulness of the Civil Rights Era…

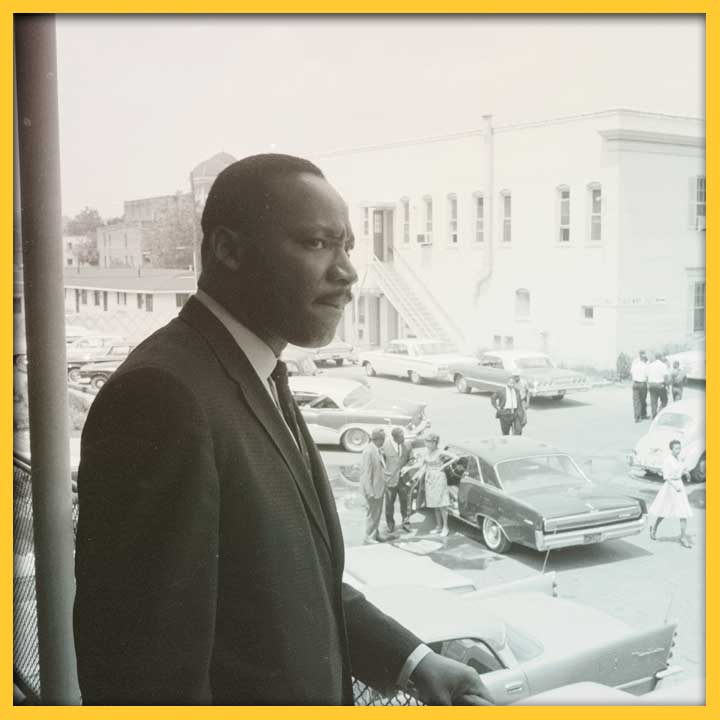

MARTIN L. KING, JR.’S DAMNING LETTER FROM JAIL

By Christopher A. Ulloa Chaves, ED.D.

“In the letter, King used a multi-disciplinary rhetorical approach that applied philosophical, theological, psychological, sociological, political, ethical and economic principles against systemic racism in Alabama…”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

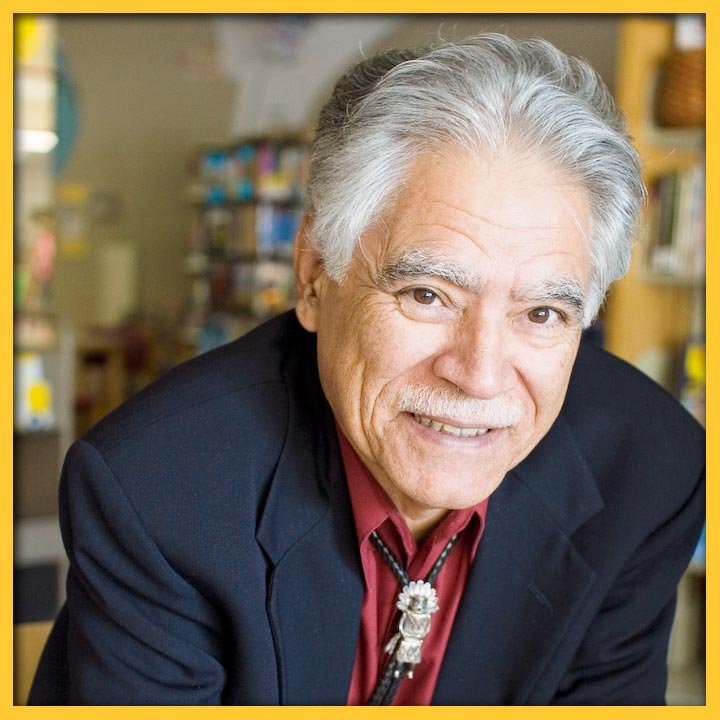

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

RICHARD ETULAIN

Richard W. Etulain is professor emeritus of history at the University of New Mexico, where he taught from 1979 to 2001. He served as editor of the NEW MEXICO HISTORICAL REVIEW and director of the Center of the American West (now the Center for the Southwest). He is the author or editor of more than 60 books. He was elected president of both the Western Literature and Western Historical associations.