SHARE:

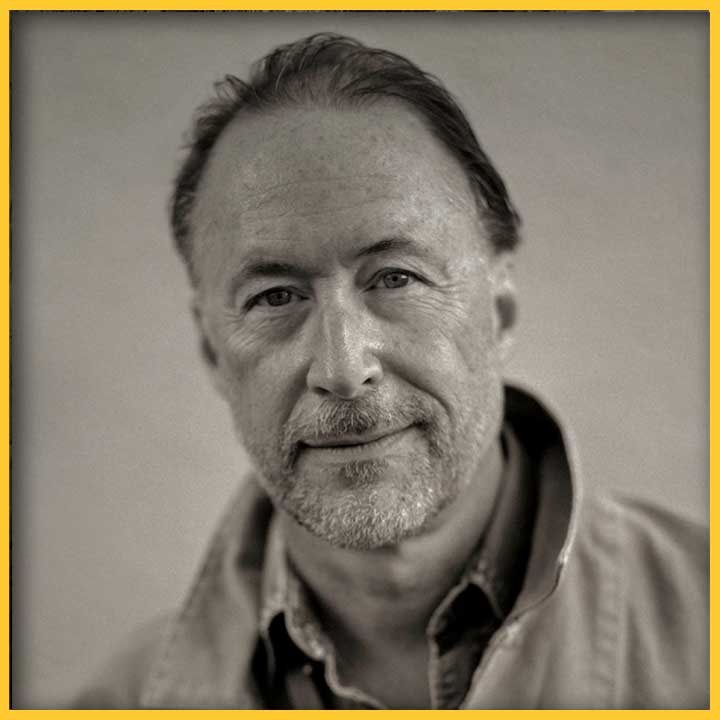

When I think about Kurt Markus, the internationally acclaimed fine-art photographer who died last month at his home in Santa Fe, I think of the word slow. Slow, as in, he always had to meditate on things, and was never in a rush. Slow, as in, he couldn’t understand why everybody seemed to be in such a hurry. Slow, as in, slow food—not that he was any sort of chef (that is one of his wife Maria’s gifts), but rather the underlying idea that we should take the time to know the origins and provenance of the things that sustain us, and always pay the keenest attention to that which is close at hand. That slowness, that sense of steady deliberation, mingled with an appreciation for right-here-and-now immediacy, was the essence of life, or at least Kurt’s life—and the secret, I think, to his art.

He was a tough buzzard and seemed almost immortal at times, but he found a way to get away from us, on June 12, 2022, after a long fight with Parkinson’s and Lewy body dementia. He was 75. What a man, what a mind, and what a life! Santa Fe will surely miss him; the whole world will.

Maybe we should start, though, with a list of some of his professional accomplishments, which could have filled a wheelbarrow. He was the recipient of many of American photography’s highest honors, including several Clio Awards and Life magazine’s Alfred Eisenstaedt Award. He also directed music videos and documentaries, wrote screenplays, and shot advertising campaigns for such diverse clients as BMW, Nike, and Kodak. His work was presented at numerous museums and prestigious emporiums of fine art, including the Peter Fetterman Gallery in Santa Monica, the Obscura Gallery in Santa Fe, and New York City’s Staley-Wise Gallery. Critics praised his “unique vision” and his “powerful sense of realism.” A reviewer in The New Yorker once called his images “quietly, unfailingly artful.” Among his many accolades, in 1994 Kurt was one of five photographers selected to participate in a 25th anniversary special edition of Rolling Stone presenting the living legends of rock-n-roll.

He may have moved easily in the world of celebrity and fine art, but Kurt was almost ferociously down-to-earth. He was a Montanan, through and through. He lived much of his adult life in Kalispell, and everyone who knew him there speaks of his unpretentiousness, his sense of humor, and his deep sense of personal honor. Suzy Moore, a longtime family friend who served as Kurt’s studio manager in Montana, described him as “such a perfect human—kind, modest, a warm spirit. Wherever he went, he was always just Kurt: A regular guy happy with simple things.”

“When I think of Kurt,” recalled one of his closest friends, Buzz Shiely, “I see a thoughtful, honest man, smiling at me from beneath a black Stetson.” Kurt was laconic, but he always asked a lot of questions. He skirted attention and usually found a way to throw the discussion back upon you. That calm self deprecation, combined with his obvious interest in other people, served him well during his often adventurous travels to dangerous places. Kurt’s work sent him all over the world, and he got himself into some seriously sticky situations. Once, on assignment in Yemen, he was kidnapped at gunpoint. The situation was looking really dire. But Kurt was such a charmer. He somehow managed to win over his captors—with that fetching smile, I guess, and those big wide-open eyes that took in everything. The kidnappers stole his camera gear, but they released him, without a scratch.

Kurt approached his photographic subjects with what he called a “simpleheartedness,” and he remained stubbornly old-school in his methods. A virtuoso in the dark room—his “escape hatch,” as he called it—he fastidiously printed and toned his own gelatin silver prints, and he was suspicious of digital sleights of hand. “I believe only in the rectangle,” he said. “Filling that rectangle with a photograph remains the most challenging thing you can do. If you have to go outside of it, bringing in other non-photographic things to put inside, you run the risk of gimmickry. For me, the most powerful expression is the simplest.”

KURT Michael Markus was born in Whitefish, Montana, on April 6, 1947, the son of Raymond Markus and Juanita Johnson. Although he grew up immersed in the great outdoors, Kurt knew from an early age that the world of ranching and field work was not a life for him. “I was born a daydreamer,” he once wrote, “and I know of no slot for one of those on any ranch.”

He attended West Point, where he was known as a thoughtful student and a natural athlete—among other sports, he threw the javelin. “At West Point, Kurt looked like some Scandinavian god—blonde hair, perfect body, all the girls fell for him,” Shiely told me. He roomed with Kurt at the military academy. After graduation, Kurt became a member of the elite U.S. Army Rangers. But he learned by hard experience that the military was no profession for him. Recalled Kurt: “When I got out of the Army in the early 70s, I knew one thing—that whatever I was going to do with my life, I wanted to love it and believe in it.”

So he trained his love and faith on photography. Inspired by Edward Weston, Paul Strand, Ansel Adams, and a handful of other fine-art practitioners, Kurt taught himself the rudiments of the craft and went to work. His camera took him, quite literally, around the world—from the Solomon Islands to Yemen, from the sand dunes of Namibia to the bottom of the Grand Canyon.

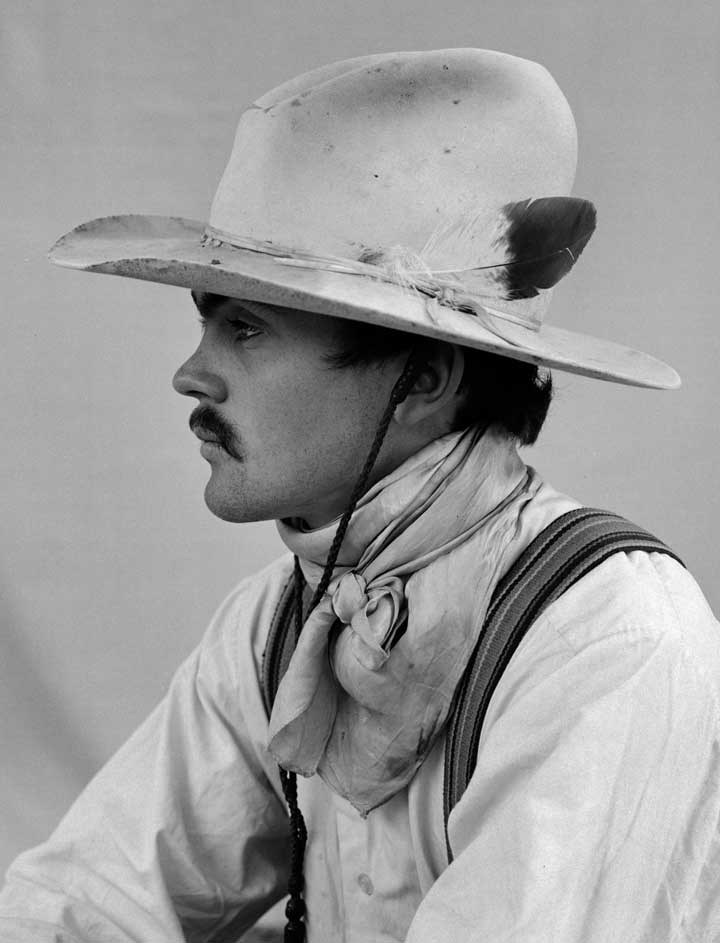

Kurt was perhaps best known for his portraits of cowboys in the American West, a subject that, given his Montana background, came naturally to him. His cowboy images—gritty, respectful, and somehow timeless—possess an elegiac quality as they document a world of toil and rugged competence that’s slowly vanishing from the American landscape. He published three books of cowboy photography: After Barbed Wire, Buckaroo, and Cowpuncher, which in 2002 was named the most outstanding art book of year by the Cowboy Hall of Fame.

“Kurt caught the spirit of the American West like no one else has,” the acclaimed photographer Bruce Weber, one of Kurt’s lifelong friends, told me. “He left behind a lasting record of the West that we won’t see done in quite the same way again. He had so much respect for that world—not just the cowboys themselves, but the horses, the saddles and gear, the landscapes. He captured it all.”

“Everything you’ve read about the West and cowboys is in some strange fashion true,” Kurt once wrote. His early work with cowboys formed a significant part of his education as a photographer. “I learned how to load film on horseback at a trot—and in driving snow,” he mused. “I learned how to be ready, to stay out of the way, and to always thank the cook.”

A quality of raw authenticity—an “unslickness,” as it’s been described—ran through Kurt’s stuff, whether his subject was a celebrity actor, a world-famous musician, a prizewinning author, an international model, or just ordinary folk. “In the world of photography, it’s very rare to find a truly original artist, but Kurt was that,” Etheleen Staley, of the Staley-Wise Gallery, told me. She describes his work as “very pure, no gimmicks, very sensitive and thoughtful, but at the same time very stylish. He was the sort of person who would not want to be called ‘stylish,’ but he was, very much so.” One thing that set him apart from so many other photographers, Staley says, was his proficiency in the dark room. “He was a master printer. There’s very little of that anymore—it’s considered artisan work, almost. It’s all gone digital. Printing his own stuff gave his images such a profound clarity and depth.”

He enjoyed cultivating a collaborative bond with the people he shot, a relationship built on mutual trust. It’s unusual, and says a lot about Kurt, that so many of the people he photographed developed life-long relationships with him. It wasn’t your typical Richard Avedon situation, a time-pressed portraitist snapping a picture and quickly moving on. Nearly all Kurt’s subjects fell in love with the guy behind the camera. In his photographs, there was a subtle tug-of-war between what was revealed and what was withheld. Kurt once wrote: “I have entered into an unspoken, unwritten, and generally inscrutable pact with the people I have photographed and lived among: If I promise not to tell all I know about them, they will do the same for me.”

Another subject that long captivated Kurt was the sport of boxing. He photographed world-champions—Mike Tyson, for example—but most of his boxing portraits paid homage to lesser-known aspirants struggling at the periphery of the sport, in far-flung places like Dublin, Mexico City, and Havana. “I see in a boxer’s body an ideal of maleness, a body both glorified by severe conditioning and humbled by punishment,” Kurt wrote. “No more muscle than necessary, no less, either. Stripped, vulnerable, they show their greatness.”

To me, it’s almost a paradox that Kurt also enjoyed a distinguished career as one of the world’s preeminent fashion photographers. How he managed to break into that high-wire world and succeed in it, in addition to all the other genres he mastered, is a wonder to me. His fashion work graced the covers and pages of such magazines as Vogue, GQ, Vanity Fair, Esquire, Elle, and Harper’s Bazaar, and he traveled the world shooting for clients that included Armani, Ralph Lauren, Calvin Klein, Banana Republic, and Liz Claiborne. Reviewers praised the steady grace and understated sensuality of his fashion photographs, noting his sense of “style and wit.” With Kurt behind the camera, wrote one observer, “models are people and not just mannequins, and they contribute their personality to the work.”

Supermodel Christy Turlington, who Kurt photographed many times at far flung locations around the world, calls Kurt “a perfectionist—so much time, care, and intelligent thought goes into every image. He subscribed to the idea that you don’t rush things that are special.” Kurt traveled to Madagascar with Turlington and climbed Kenya’s Mt. Kilimanjaro, among other shared adventures. “Even though he was one of the very best photographers in the fashion world, to call him a fashion photographer wouldn’t be quite accurate,” she told me. Turlington described a session with Kurt as “a study in craft,” in which photographer and subject are creative co-conspirators. “He sees the space, the angles, the composition, the possibilities. His mind is always going. But there is a quiet curiosity and a sense of respect that encourages you to be free and allows surprises to happen.”

Kurt attributed the success of his multi-faceted career to relentless hard work, but also to a willingness always to remain open to unexpected opportunities. “I think the really valuable experiences are the ones that come out of nowhere while you’re plodding along on a journey,” he said. “But persistence is valuable, too. I always worked hard, always showed up. Sweat is part of the equation.” He believed, almost mystically, that his camera had a will of its own. “It is an instrument of serendipity,” he wrote, “and it takes its own pleasure with things and people apart from my best intentions and desires.”

In recent years, Kurt spent much of his time capturing one of the world’s most spectacular and iconic landscapes, Monument Valley. I think that of all his many subjects, his Monument Valley pieces speak to me with the deepest resonance. His images of that Navajo sandstone wilderness, through every season and in all sorts of weather, possess the same entrancing elements that imbue his world-class portraits—a dignified sensuality, an aversion to gimmick, a granular realism, and that same spirit “simple-heartedness.”

Photographer Bruce Weber seems to agree. “Kurt’s Monument Valley work is just extraordinary,” he told me. “He went there for years and although he caught something different with every visit, the images always had the same quality of reverence and majesty.”

Wherever his Linhof field camera took him, Kurt regarded himself as a blessed man, a dumbstruck pilgrim in the world of photographic art. “I consider it a gift to have found photography and made my life in it,” he said. “I never thought of it as a job. I’ve always associated the click of the shutter with the word ‘Yes.’”

I visited Kurt a few weeks before he died. His hands trembled slightly as he poured me a glass of Topo Chico mineral water—his favorite—and then, hanging on my arm for balance showed me around his darkroom and his meticulously organized archive. What a gold mine that place is! Mountains of negatives, drawer after drawer of stuff housed in a climate-controlled bunker, with a few Navajo rugs tastefully placed hither and yon. Everything was exquisitely labeled. BB King. Laura Dern. John Mellencamp. Jewel. Meryl Streep. Cormac McCarthy. Amy Grant. Evel Knievel. Carole King. Jim Harrison. Joan Baez. Cindy Crawford. John Lee Hooker. On and on it went, like a registry of celebrity from the 1970s, 80s, 90s, and into the new millennium. And I was thinking, man, who didn’t Kurt Markus photograph?

Kurt’s cremated remains will be buried in Tuscarora Cemetery in Nevada’s Great Basin—a lonesome place not far from where he shot some of his early portraits of cowboys. When I asked him why he picked such a remote and forlorn spot for a gravesite, he quipped, with a barely perceptible grin: “I didn’t want people to feel guilty for not coming to see me after I’m gone.”

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

A DIFFERENCE-MAKING BOOK

By Richard Etulain

“Many authors hope their histories, novels or other writings will make a difference — that their works will catch readers’ attention and influence their thinking and actions.”

CELEBRATE CONSTITUTION AND CITIZENSHIP DAY EVERY DAY, NOT JUST SEPT. 17TH

By Maryam Ahranjani

“As a teacher and mother and child of immigrants who now teaches Constitutional Rights to law students, this day is always a special one for me.”

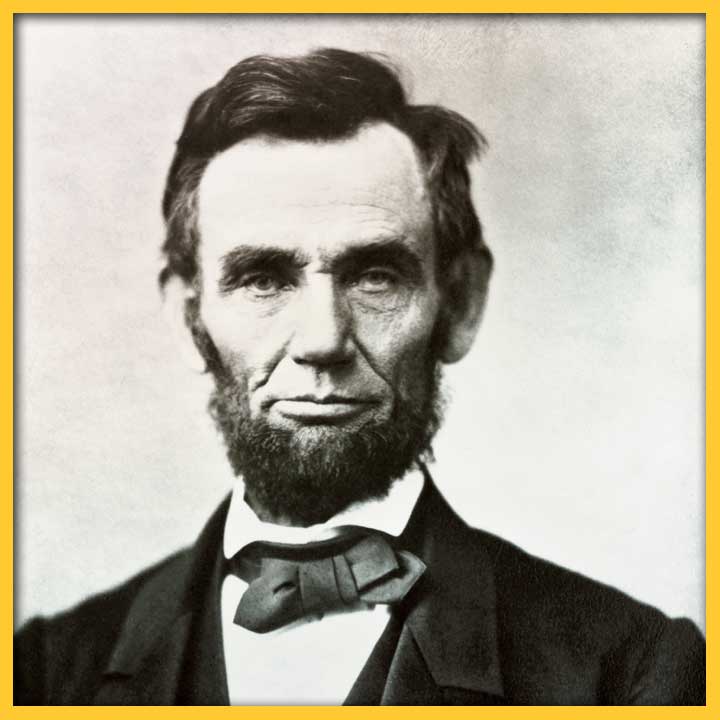

THE THIRTEENTH AMENDMENT THAT NEVER WAS

By Brandon Johnson

The 13th Amendment, guaranteeing the abolition of chattel slavery in the United States, is one of the crown jewels of the American Constitution.

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

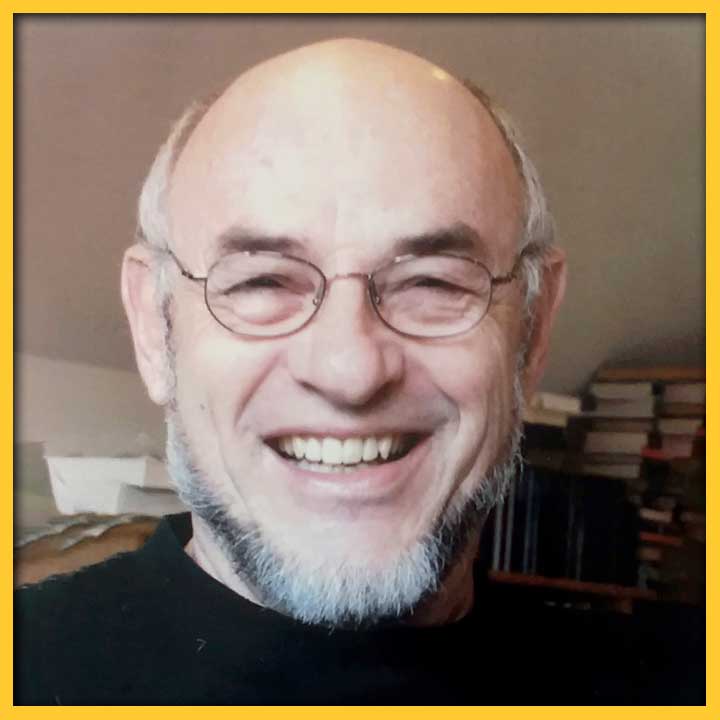

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

HAMPTON SIDES

Narrative historian Hampton Sides is the author of the bestselling histories Ghost Soldiers, Blood and Thunder, Hellhound on His Trail, In the Kingdom of Ice, and On Desperate Ground. A native of Memphis and a graduate of Yale, he is a member of the Society of American Historians and was a recent fellow at the Santa Fe Institute. He’s now at work on a book about the fateful final voyage of Captain James Cook. He lives in Santa Fe with his wife, Anne Goodwin Sides.