WHY IS EL PASO IN TEXAS?

Today, Southern New Mexicans frequently cross the border to El Paso, TX to enjoy shopping and entertainment, perhaps appreciating the culture without understanding the long history of why El Paso feels so much more familiar than other Texas communities. Arguably, El Paso is the oldest New Mexican settlement. So how did it end up in Texas?

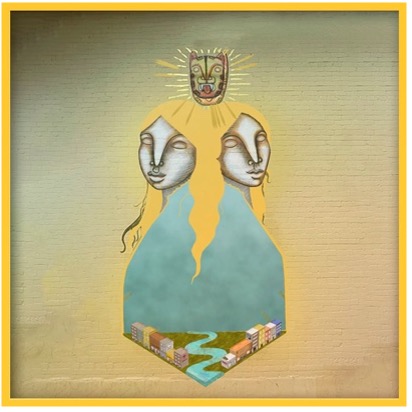

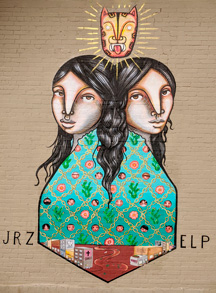

PHOTO CAPTION: Mural near International Border Crossing as seen with AR viewer. (Screengrab of the Augment El Paso app, collected by Ellen Dornan)

SHARE:

Today, Southern New Mexicans frequently cross the border to El Paso, Texas, to enjoy shopping and entertainment, perhaps appreciating the culture without understanding the long history of why El Paso feels so much more familiar than other Texas communities. Arguably, El Paso is the oldest New Mexican settlement. So how did it end up in Texas?

In April 1598, the colonists accompanying Juan de Onate paused by the banks by the Rio Bravo del Norte to hear him proclaim “In the name of the most Christian king, Don Philip … I take and seize tenancy and possession, real and actual, civil and natural, one, two, three times … and all the times that by right I can and should … without limitation.” Thus was New Mexico formally established, at El Paso del Norte. He marked the site on his map of the colony, just upstream from the pueblo of Senecu.

In 1680, as the Pueblo Revolt swept through Spanish settlements in northern New Mexico, colonists fled down El Camino Real to regroup in El Paso, and many never returned. The first post-Revolt map we have is Fray Juan Miguel Menchero’s, possibly made with the assistance of an El Paso native, Bernardo Miera y Pacheco. The priest’s 1745 map shows a chain of Pueblo missions and towns along the river, including San Lorenzo (later San Elizario), Senecu, Ysleta del Sur and Socorro, all protected by the presidio of El Paso del Norte.

The riparian land around El Paso was good wine growing country, and despite pressures from the “Faraon” Apaches and the Comanche, communities spread along both the north and south bank of the river, as Miera y Pacheco shows in his 1758 map. When Americans arrived (illegally) in 1810, Zebulon Pike noted that a network of roads connected the presidio to an expanding number of settlements, still mostly on the south bank. The north bank seems to have remained a dangerous place to get attacked through the early territorial period. After Mexican independence, Americans started streaming in and found the area conducive to conducting profitable trade with the flourishing city of Chihuahua. Their community, on the less-populated north bank, became known as Magoffinsville, after the prominent merchant James W. Magoffin.

The Magoffin family played a role in the seizure and occupation of New Mexico by the United States’ Army of the West. Whether it extended to bribing New Mexico’s Governor Armijo to surrender will probably remain a point of contention and speculation. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo meant to set the international border in El Paso, on the same shores of the Rio Grande where Onate had sworn his pledge nearly 250 years before. However, Disturnell’s inaccurate map, combined with crummy instruments (and a border commissioner more intent on sightseeing than surveying) instead established the border through Mesilla, despite the vehement protests of surveyor A.B. Gray, who tried to interrupt the proceedings as they erected the monument. By the time a second survey commission had been established, the Gadsden Purchase re-

In 1855, Brig. Gen. William H. Emory undertook to survey the New Mexico border from that point, constructing a dozen markers between El Paso and the Colorado River. Before he even started, Congress rather heedlessly established the border between New Mexico and Texas. In the flawed Boundary Compromise of 1850, Texas backed down from claims to owning New Mexico right up to the eastern bank of the Rio Grande in return for the United States forgiving its war debt. New Mexicans did not seem to have a choice in the matter, being widely perceived by Americans as the booby prize of Mexican cession. A later general would comment, “Except for its political geographical position, the Territory of New Mexico is not worth a quarter of the blood and treasure expended in its conquest.” And so with two straight flourishes, the border was established, again with El Paso as the starting point, from the 32nd parallel to the 100th meridian, then north.

The Gadsden Purchase made the establishment of Fort Bliss and the Southern Pacific Railroad possible, driving settlement on the American side of El Paso, now a town lying across the Texas and Mexico border. The Texas town of El Paso incorporated in 1773, swallowing up Magoffinsville, Fronteras, and eventually all the historic communities. In 1888, the Mexican town of El Paso del Norte changed its name to Ciudad Juarez, obscuring its New Mexican past in favor of a new, Mexican, identity.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

SPACESHIPS, RAY GUNS, AND LIFE LESSONS

By Melinda Snodgrass

“science fiction allows you to discuss difficult and fraught topics in what is a safe space and at arm’s length.”

LITERATURE AS GUIDEPOSTS ON MY IMMIGRANT JOURNEY

By Kei Tsuzuki

“What I have learned from books is that there is no one story that explains the world to us or captures our identity entirely. There is power in the specificity of each of our stories…”

A DIFFERENCE-MAKING BOOK

By Richard Etulain

“Many authors hope their histories, novels or other writings will make a difference — that their works will catch readers’ attention and influence their thinking and actions.”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

ELLEN DORNAN

Ellen Dornan serves as the CIO and the Digital Humanities Program Officer. Ms. Dornan has worked with the Council since 2001, serving as webmaster, NHD judge and junior division coach, and a scholar on grant projects and the Centennial Online Atlas of Historic New Mexico Maps. She joined as full-time staff in January 2016.