SHARE:

The noted Western novelist and historian Wallace Stegner once wrote, “I have been convinced for a long time that what is mistakenly called middle of the road is actually the most radical and difficult position — much more difficult and radical than either reaction or rebellion.”

Probably Stegner was hesitant to label himself a middle-of-the-road thinker because the centrist position is often dismissed as “waffling,” identified as the stance of someone who cannot make up his or her mind on important issues and thus resorts to dodges or inaction.

But back to the central question: Is there value in staking out, after considerable thought on significant ideas, a position between extremes, equally distant from the far left and far right? I am convinced there is, as this brief piece suggests.

A reminder as an opener: Our democratic system was organized, put into action, and pushed forward through a series of compromises among strong-willed leaders. Founding fathers, representatives at the Constitutional Convention, and our first presidents realized they had to give in, to compromise, to gain democratic organization and policies. Much much later, especially in the late-20th and early-21st centuries, we seem to have forgotten the large need for many compromises politically.

Why this reminder? Because adopting a middle-of-the-road position after thorough study of thoughts emanating from the progressive and conservative sides on controversial issues prepares one as a thinker or leader for a more comprehensive understanding of conflicting questions.

In fact, middling opinions are often necessary to understand and evaluate our past. Think, for example, of some of our presidents. George Washington and Thomas Jefferson were superb leaders — but they were also slave owners. Many think Abraham Lincoln was our greatest president, and yet he was, by modern definitions, a racist, not believing whites and blacks in all ways equal. Theodore Roosevelt, another strong leader, nonetheless detested Indians. Franklin Roosevelt led the country through a traumatic depression and war and yet egregiously tried to enlarge the Supreme Court to further his own legislative desires.

Middle-of-the-road thinking prepares one for seeing and understanding the spectrum of issues in a major debate, as well as for which of the segments are the most important. When this comprehension is accomplished, the middle of the roader will realize on which positions he or she must continue to stand and those on which compromises are acceptable.

A key to middle-of-the-road opinions is moving away from “either-or” and embracing “both-and” thinking. Comprehending competing positions prepares one much better for eventual compromises than locked-in, one-sided reasoning. Those who understand both the traditional Democratic support for a strong central government and the corresponding Republican preference for local or personal control are much better poised to work out an eventual agreement. The same for those who comprehend and simultaneously consider the important meaning of “Black Lives Matter” and the need for strong police forces.

Think of American political leaders of the past who provided emulative models of centrist positions. Abraham Lincoln is an example. Like his political idol Henry Clay, Lincoln could stand for compromises. For instance, when in Congress during the Mexican-American War, he roundly criticized President James K. Polk and the war but also voted for legislation supporting soldiers. As president, he was reluctant to attack slavery in the South until he announced the Emancipation Proclamation in 1862-63. but all along he stood stoutly against expansion of slavery into the trans-Mississippi West.

In New Mexico, although some might point to bipartisan efforts of Senators Pete Domenici and Jeff Bingaman as examples of middle-of-the-road actions, the stances of the earlier New Mexico Senator Bronson Cutting are much more clear-cut. Cutting, a Republican, displayed his centralist (centrist?) leanings by supporting legislation his president Herbert Hoover opposed and by voting for Democrat Franklin Roosevelt rather than Hoover in the presidential election of 1932. When in the U. S. Senate, Cutting opposed aspects of censorship legislation but voted for New Deal measures on banking reform. Cutting gained widespread support from both Republicans and Democrats in New Mexico.

On our present political scene, several senators stand out as examples of moderate or centrist politicians. Among the Republicans, the most recognized moderates or bipartisan leaders are Mitt Romney, Susan Collins, and Lisa Murkowski; among the Democrats, Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema. Party regulars on both sides are upset when these senators work across aisles to support the actions of the opposition party. Still, these and a few others have been keys to getting bipartisan legislation through the Senate.

Early in his presidency Joe Biden called for comprehensive legislation under an umbrella he labeled the Build Back Better plan. It was far-reaching and expensive and opposed by Republicans and some Democrats. But before long a group from both parties worked out a compromise piece of legislation later titled the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. A small number of representatives from both parties negotiated a piece of legislation that lowered Biden’s original costs and narrowed its coverage but also addressed much-needed repairs to and expansion of the nation’s infrastructure. The steps to the successful passage of this compromise bill provide an emulative model for the future: Assemble a small group of influential congressional leaders, work out a bipartisan framework, and sell the basic idea to the Republicans and Democrats. Such centrist beginnings seemingly assure more successes than partisan efforts.

In short, a quick overview of middle-of-the-road stances among thinkers, acters, and politicians suggests that placing more emphases on centrist thinking could very well help us to move beyond the partisan battles that lock up so much of our contemporary American political scene.

This column was generously funded by a grant from the Mellon Foundation to explore the question of Democracy and the Informed Citizen.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

NEW MEXICO’S AMAZING BLACK HISTORY

By Rob Martinez, State Historian of New Mexico.

“African history runs deep in New Mexico. Black history is often framed within the institution of slavery, but in New Mexico, New Mexicans of African descent were ambassadors, explorers, colonists, soldiers, cowboys, discoverers, settlers, businessmen, educators, and much more.”

SCANNING FOR STORIES

It was a Friday afternoon in November and I was driving on a state road through the hills of the Mimbres Valley. The entire landscape was bathed in a golden hue because the tree leaves had made their full conversion to a bright yellow color just before falling off the branches.

REFLECTIONS ON THE LOSS OF A NEW MEXICO CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER

By Carlyn N. Pinkins, M. A.

“The Dr. Harold Baileys of the world should inspire us all to do what we can to leave our communities, our towns and cities – our great state – better places than we found them. While we do our part to create the Dr. Harold Baileys of the future, we should also strive to make sure that the Dr. Harold Baileys of our past and present are never forgotten.”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

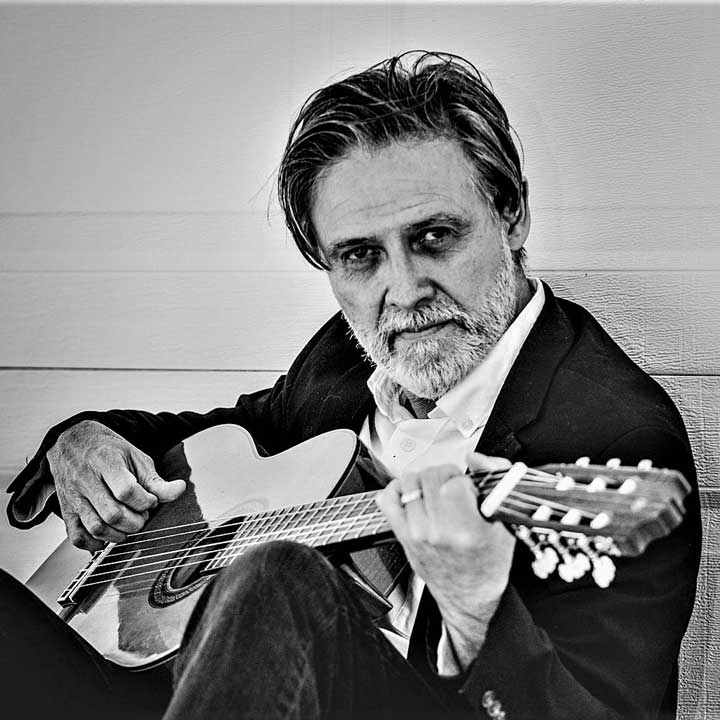

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

RICHARD W. ETULAIN

Richard W. Etulain is professor emeritus of history at the University of New Mexico, where he taught from 1979 to 2001. He served as editor of the NEW MEXICO HISTORICAL REVIEW and director of the Center of the American West (now the Center for the Southwest). He is the author or editor of more than 60 books. He was elected president of both the Western Literature and Western Historical associations.