SHARE:

Many authors hope their histories, novels or other writings will make a difference — that their works will catch readers’ attention and influence their thinking and actions. Unfortunately, this dream rarely comes to fruition; not many books are difference-making. But University of New Mexico history professor Gerald D. Nash’s book, The American West in the Twentieth Century: A Short History of an Urban Oasis (1973), was just that. It especially made a difference among interpretations of the modern American West.

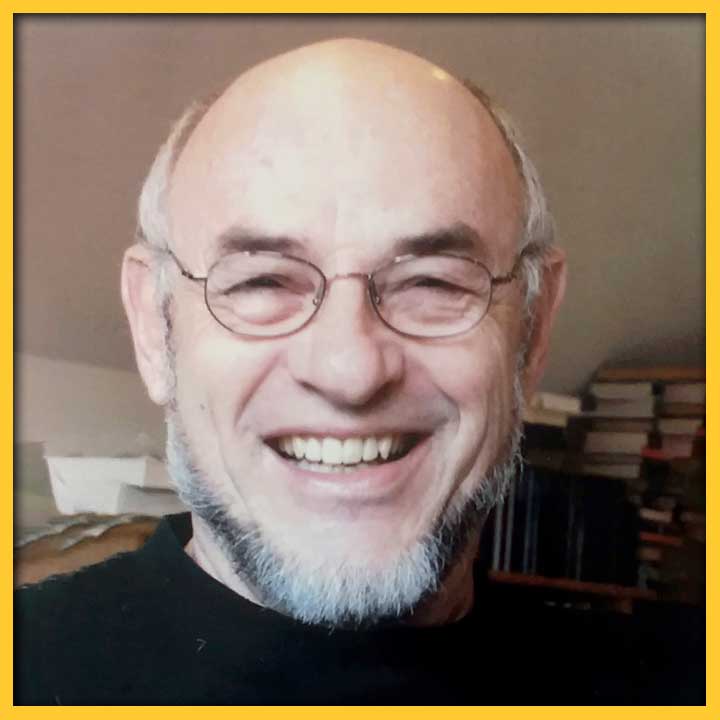

Dr. Nash, of Jewish heritage, was educated on the East and West Coasts. After his family escaped Nazi Germany and immigrated to the New York City area, Nash completed his public education there and earned a bachelor’s degree from New York University and a master’s from Columbia University. Then, moving to the West Coast, he completed a doctorate in American history at the University of California, Berkeley in 1957.

Early in his teaching career, Nash quickly established a reputation for his writings on U.S. and western American economic history. He turned out several books and numerous essays, most of which dealt with economic or political topics. After teaching elsewhere for a few years, Nash moved to the University of New Mexico in 1961, where he remained until retirement in 1995. During the years from 1974 to 1980, he served as department chair.

When Nash’s The American West in the Twentieth Century appeared in the early 1970s, reviewers quickly noted its major contributions. They pointed to the author’s valuable coverage of economic and political subjects without his overlooking important social and cultural topics. Critics also saluted his balanced account. Rather than push his own individualistic conclusions, Nash provided a comprehensive perspective, avoiding one-sided interpretations.

Commentators were right, too, in noting the important breakthrough in Nash’s coverage. His work was the first account to extensively cover the 20th-century American West. Historians often have been reluctant to write about the near past, usually remaining at least a generation or two away from the present. But Nash covered western history up to 1970, thus furnishing the pioneering overview of the modern American West.

But nearly all reviewers missed another important contribution of Nash’s significant volume. It was also a notable difference-maker in the historiography of the American West. Frederick Jackson Turner’s Frontier Thesis had dominated writings about the West from its appearance in the 1890s until roughly the mid-20th century. Nothing had emerged by 1970 to clearly replace Turner’s frontier interpretation. University of Oregon historian Earl Pomeroy in his book The Pacific Slope (1965), and Pomeroy’s student — and Gerald Nash’s close friend, Gene Gressley — furnished partial answers in covering regions and selected topics of the post-1900 West, but their contributions were limited.

Nash moved beyond Pomeroy, Gressley and others in dealing with the entire West and with all the post-1900 West. Plus, he transitioned away from Turner and his followers’ fixations on the earlier, rural frontier West and on to the modern, urban West as the central topic for understanding the American West in the 20th century. In short, Nash’s overview of the modern American West not only introduced a new subject to the field; he also led a path away from Turnerian views to a new stress on a modern urban West.

Gerald Nash’s pathbreaking volume should be an illuminating lesson for all writers of history. The hesitancy of historians to deal with the recent past — as close up as yesterday — should be understood, but not encouraged. Too often historians view recent history as the home country of journalists, not the residence for historians. Wrong. We need to see history up to the present, to know and understand trends of the previous generation or two. Such illuminations will help us to be even more thoughtful about the present and planning for the future.

Let me be even more specific. We are now about one quarter of our way through the 21st century, but we still do not have, as examples, a historical overview of the first 20 years of the post-2000 United States, the American West, or even New Mexico. We need these accounts; they would be valuable sources for us. Such overviews could help us to see patterns of the past and help us lay out a better future. Nearly a half century ago, Gerald D. Nash proved how difference-making such a recent history could be.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

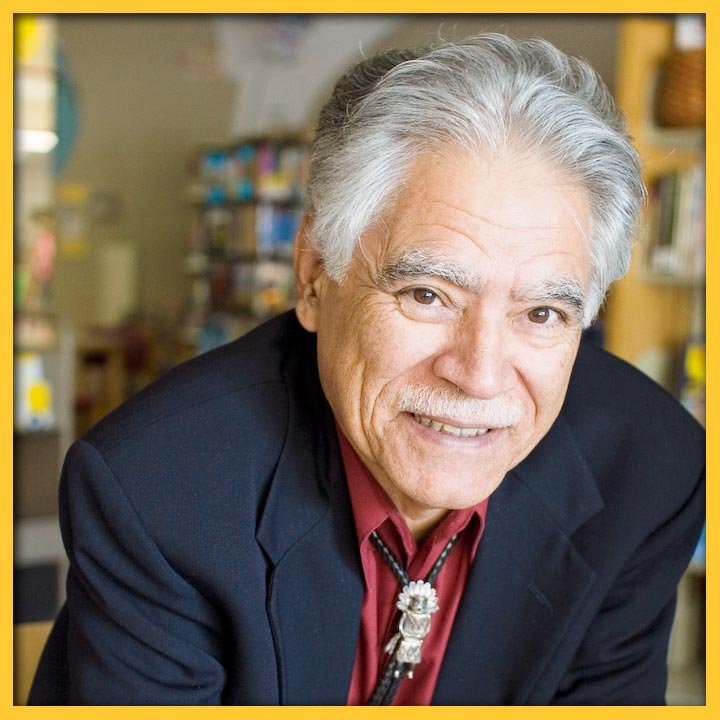

RUDOLFO ANAYA: CATCHING CULTURES IN BLESS ME, ULTIMA

By Richard Wayne Etulain

Anaya greatly expands the cultural contributions of his novel by combining the usual (Bildungsroman—growing up theme) with the unusual (complex, diverse New Mexico Hispanic culture)…

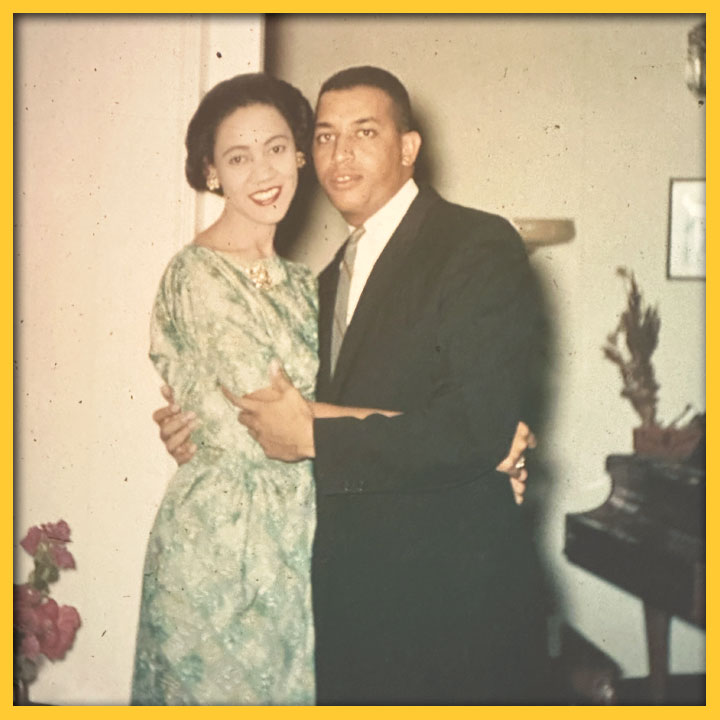

UP BY OUR BOOTSTRAPS; TWO LIVES IN RETROSPECT

By Finnie Coleman

I found myself fascinated with Dr. McIver’s transition from the stultifying hopelessness of the Segregation Era to the wistful hopefulness of the Civil Rights Era…

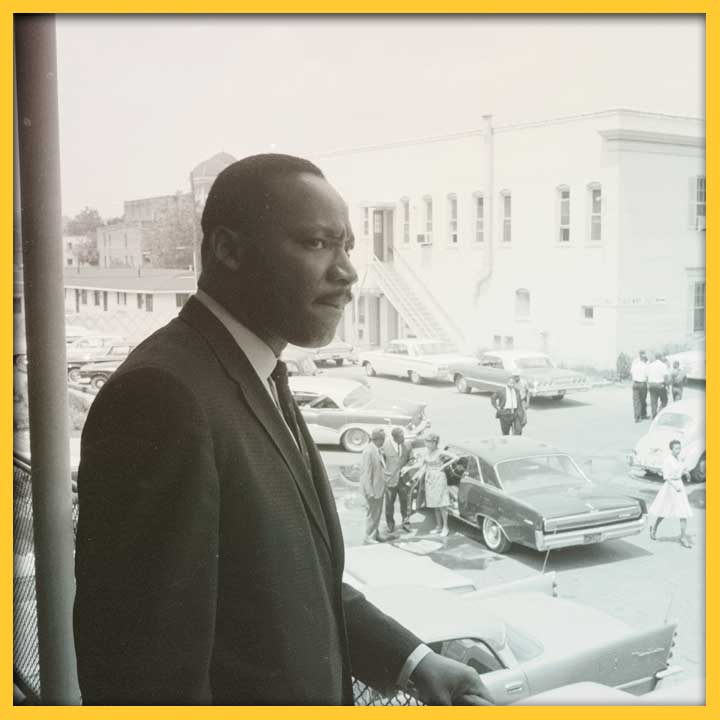

MARTIN L. KING, JR.’S DAMNING LETTER FROM JAIL

By Christopher A. Ulloa Chaves, ED.D.

“In the letter, King used a multi-disciplinary rhetorical approach that applied philosophical, theological, psychological, sociological, political, ethical and economic principles against systemic racism in Alabama…”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

RICHARD ETULAIN

Richard W. Etulain is professor emeritus of history at the University of New Mexico, where he taught from 1979 to 2001. He served as editor of the NEW MEXICO HISTORICAL REVIEW and director of the Center of the American West (now the Center for the Southwest). He is the author or editor of more than 60 books. He was elected president of both the Western Literature and Western Historical associations.