AMERICA'S CONSTITUTION: A MACHINE THAT DOES NOT RUN BY ITSELF

The protection of democracy is not simply the obligation of elected officials and the courts. Rather, the preservation of constitutional democracy rests on the willing engagement and widespread participation of the people…

PHOTO CAPTION: “Scene at the Signing of the Constitution of the United States.” Credit: Howard Chandler Christy, 1940.

SHARE:

When the Founding Fathers drafted America’s frame of government in Philadelphia during the constitutional convention of 1787, they knew they had begun a journey and not completed a task. By creating a government based on the idea that the people were the sovereign foundation for any legitimate government, they appreciated their dramatic departure from the past. Most governments in the world at the time were monarchies or expressions of raw power. Few examples existed of a people deliberately creating their own government. However, the creation of America’s government was tied to an on-going role of the people to participate and monitor their government.

The Framers of the Constitution were acutely concerned with the possibility that the people might be misled and act impulsively. Some of the Framers hoped that inserting checks and balances in the structure of government would make the democracy less subject to volatility. All of those who drafted the Constitution stressed the importance of an informed and educated people for a popularly-based form of government to flourish. They knew that momentary passions might seize the public mind, but in the end, they had no choice but to take the risk, that having committed themselves to the constitutional principle that ultimate governmental legitimacy rested on the people, democracy must rely on the people’s choices.

It is often said that the Framers did not establish a democracy, but rather a republic. This observation fails to acknowledge the democratic commitment that lay at the foundation of the Constitution. The Constitution did not establish a “pure” democracy in the sense of each person voting directly on laws. But even with the people’s representatives serving as lawmakers, the republic framed by the Constitution was destined to have a democratic legacy. That legacy was insured when the Framers actually involved the people in forming a new government and rested the foundation of the Constitution on the idea of a sovereign people.

Arguably the most crucial aspect of the Constitution is not to be found in any specific text or its description of the structure of government. Rather, the most important principle rooted in its foundation is a commitment to the promise of equality. By rejecting the inherent inequality of monarchies that distributed rights and political power by the accident of birth, the American revolutionaries and the Federal Framers paved the way for the aspirational principle of egalitarianism and the promise of equal justice under law. The pamphleteer Thomas Paine captured the “Common Sense” of the American revolutionary rejection of hereditary privilege by asserting that since “all men being originally equals, no one by birth could have the right to set up his own family in perpetual preference to all others forever.”

To be sure, significant inequalities existed at the time of the framing and persisted for a long time—the exclusion from political participation by women, those lacking property, Native Americans, and African Americans come to mind. Still, the commitment to the principle of “the people” as the sovereign source of government inevitably formed a logic and created pressure to expand the definition of the “the people” to include groups previously excluded. That work of inclusion continues today. The full and true realization of equality still remains an aspiration more than 200 years later.

The key to our constitutional democracy and the vital importance of understanding the history and significance of the Constitution rests on ensuring that the advance toward meaningful equality continues. American democracy cannot be taken for granted. An educated and vigilant people is essential to resist those who would displace the equal protection of “the people” by either self-selected elites or would-be dictators. Each generation must dedicate itself to the on-going project of democracy and failure to do so jeopardizes the hopeful experiment advanced in 1787. The protection of democracy is not simply the obligation of elected officials and the courts. Rather, the preservation of constitutional democracy rests on the willing engagement and widespread participation of the people, aware of the fact that they form the critical part of the sovereignty on which the Constitution was founded.

At the end of the constitutional convention, as delegates were signing the Constitution, Benjamin Franklin recalled that during the proceedings he had frequently speculated about the carved image on the back of the chair used by George Washington in presiding over the convention. It depicted a sun, but during the convention’s proceedings Franklin was uncertain if the symbol was a setting or rising sun. With the completion of the draft Constitution, however, Franklin concluded it represented a rising sun. He showed similar hopeful optimism in replying to a woman who asked him after the convention whether the delegates had produced a republic or a monarchy. His answer was “A republic . . . if you can keep it.” His warning is a useful reminder for our own times.

The Framers understood that the Constitution was not set in stone. It is a dynamic, living document that would necessarily change as the people exercised their right to vote, to hold their elected representatives accountable, to engage in grass-roots activity, and to protect their rights from tyranny.

This column was generously funded by a grant from the Mellon Foundation to explore the question of Democracy and the Informed Citizen.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

SPACESHIPS, RAY GUNS, AND LIFE LESSONS

By Melinda Snodgrass

“science fiction allows you to discuss difficult and fraught topics in what is a safe space and at arm’s length.”

LITERATURE AS GUIDEPOSTS ON MY IMMIGRANT JOURNEY

By Kei Tsuzuki

“What I have learned from books is that there is no one story that explains the world to us or captures our identity entirely. There is power in the specificity of each of our stories…”

A DIFFERENCE-MAKING BOOK

By Richard Etulain

“Many authors hope their histories, novels or other writings will make a difference — that their works will catch readers’ attention and influence their thinking and actions.”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

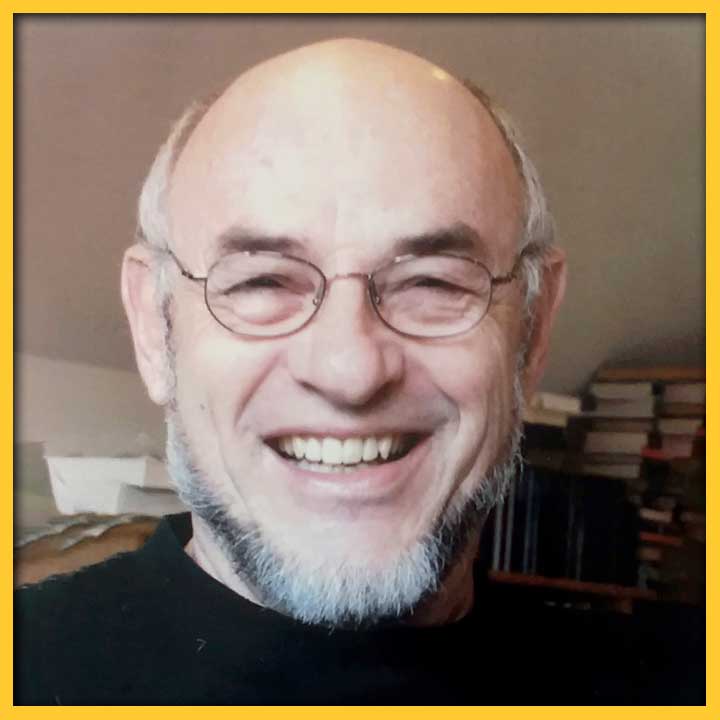

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

CHRISTIAN FRITZ

Christian Fritz is Emeritus Professor of Law at UNM School of Law where for many years he taught legal history. He is the author of American Sovereigns: The People and America’s Constitutional Tradition Before the Civil War (Cambridge University Press, 2008).