SHARE:

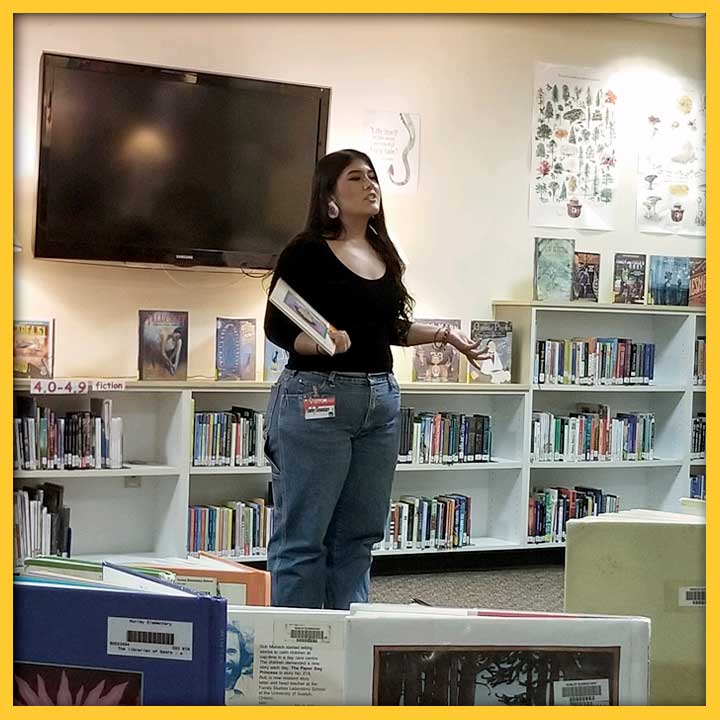

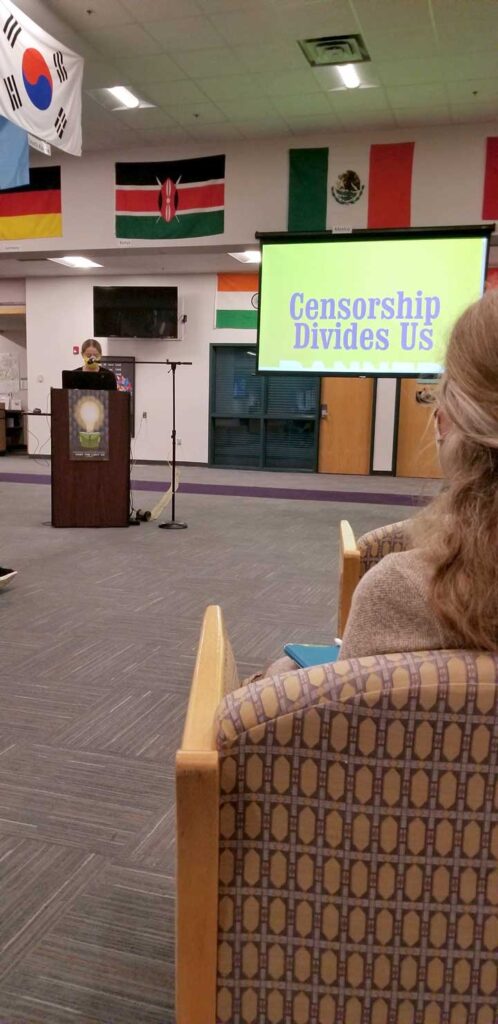

As both an educator and a writer, I care deeply about the freedom to read. At Western New Mexico University in Silver City, N.M., where I teach English, each fall my students do a special project for Banned Book Week. It’s a collaboration with the Miller Library librarians and staff, and I work closely with Mindy Sandoval, the Head of Public Services. It has been great to see how much this event has grown over the years, such as including middle school students from the Aldo Leopold Charter School, the WNMU Queers and Allies Club, the Grant County Poet Laureate, the WNMU Writer-in-Residence, and others. We have had banned books donated to our students by faculty, SWAG — a local used bookstore, and COAS Bookstore and Casa Camino Real Book Store & Art Gallery in Las Cruces. A local elementary, Hurley Elementary School, invited my students to give a presentation about banned children’s books to their library classroom. On the one hand seeing so many people involved and caring about the freedom to read is awe–inspiring, but on the other hand, it’s sobering and saddening that this issue is still current.

There was a time not too long ago when my college students marveled at this thing called “book banning,” as if it were only a movement of the “dreaded, ancient 1980s and 1990s”. I would tell them about one of the most banned writers from that time, Judy Blume, and the death threats that she received for having the gall to write about girls having their periods or teens having sex. At a lecture series I attended where Blume spoke, she joked that she wrote Forever, one of her mostly frequently banned books, because she wanted to write a book where a teenage couple had sex, and nothing bad happened — the boy wasn’t a villain, and the girl wasn’t destroyed or punished. At this lecture series, I remember looking around at this room full of women, many of whom raised their hands to request the mic so that they could express their gratitude to Blume. They gushed to Blume about how her stories and heroines personally spoke to them, helping them navigate their own girlhood and young womanhood. That awe and gratitude is long-lasting; in 2023 Amazon created a documentary, Judy Blume Forever, which includes multiple interviews by readers who felt seen and heard by Blume, who felt a connection to the flawed but honest heroines. As a teen, I read Forever and loved it. As of this March, this book was one of 80 books removed from the stacks of a Florida School District (source).

In 2022, it was reported by the American Library Association that the number of books challenged was the “highest number of attempted book bans since ALA began compiling data about censorship in libraries more than 20 years ago” (source). Many of the books challenged are those written by and about traditionally marginalized populations — LGBTQ+, people of color, women. Attempting to ban literature proves how potentially powerful literature can be. Literature can be a mirror in which you see your experiences represented, but also can be a door through which you can walk through experiences vastly different from your own and come to an understanding.

I see this in how my students respond to the book selections they read for the Banned Book Week Project. I remember one student immediately checking out the full book of The House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros, telling me that she had never read a book that connected so much to her family, her neighborhood and her voice. I also remember other students telling me how The Devil’s Highway by Luis Alberto Urrea taught them to see undocumented immigration differently, telling me how much they cared for the men in the story, how much they wanted the men to survive.

Is this the danger perceived by those who try to ban books? This increase of empathy? Reading books, especially those that are character-driven, increases empathy, as multiple studies demonstrate, the first widely recognized one dating back to 2013 (source). If you are a reader, it’s likely that your experience matches these results. If you have cried or felt happy or became angry from what a character was going through, then you were transported emotionally into the story. Is this level of connection perceived as dangerous by those who try to ban books? Or is it a case of misguided protection, as Blume said in a PBS interview this April:

And I hear there are groups around here, and they will say. . .that we want to protect our children. We don’t want them to read anything that isn’t nice. We don’t want them — you know, everything should have a happy ending. We don’t want — basically, we don’t want them to think. We don’t want them to ask questions. You know, we just want their lives to be perfect.

Well, that’s not possible, because lives are not perfect, and kids have a lot going on. And you can’t control that. Youcannot control that. (Source)

Some of the stories about book banning literally hit closer to home for my students — the Alamogordo book burning of Harry Potter in 2001, the banning of the Tucson School District’s Mexican American studies program in 2008, the banning and burning of Bless Me, Ultima in N.M. in 1981 and 1982. By students practicing their voices, by reading books that represent their experiences and those that don’t, there may be hope yet. After all, it was students who took a banned book case to the Supreme Court in 1982 (source), the very same year that Banned Book Week started.

“Banned Books Student Presentations and Melodrama” by Jennifer Olson

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

CULTURE ALSO COMES IN THROUGH THE KITCHEN

By Teresa Dovalpage

“Here in Hobbs, where I currently live, the Cuban community, very small when we moved here seven years ago, is growing fast.”

RUDOLFO ANAYA’S MAGIC WITH WORDS

By Chris Chaves

“It seems that, for Anaya at least, libraries and the magical words hidden in their books can serve to impart knowledge, facilitate love, and encourage empathy about others.”

ECOLINGUISTICS AND HOW LANGUAGE CAN SAVE THE WORLD

By Monika Dziamka

“It’s hard to talk about gender, equality, and equity without also talking about issues surrounding sustainability and the environment—which in turn relate to issues of power, colonialism, and capitalism.”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

HEATHER FRANKLAND

Originally from Indiana, Heather Frankland currently lives in Silver City, NM where she is an Assistant Professor of English Composition at Western New Mexico University. Heather has lived in NM for cumulatively, about a decade, and she holds both a MPH and an MFA from New Mexico State University. She also served in the Peace Corps in Peru and Panama. She is a published writer and has a chapbook of poetry coming out this fall, “Midwest Musings,” from Finishing Line Press.