RUDOLFO ANAYA'S MAGIC WITH WORDS

It seems that, for Anaya at least, libraries and the magical words hidden in their books can serve to impart knowledge, facilitate love, and encourage empathy about others.

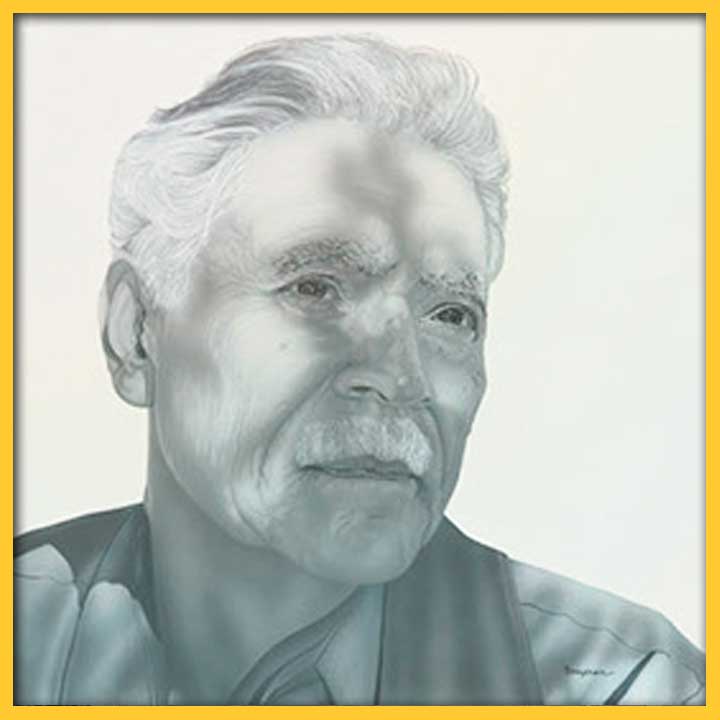

PHOTO CAPTION: Drawing of Rudolfo Alfonso Anaya by Gaspar Enríquez, 2016. Courtesy of National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; commission made possible through the Smithsonian Latino Initiatives Pool, administered by the Smithsonian Latino Center.

SHARE:

Hay un hombre con tanto dinero

Que no lo puede contar

Una mujer con una sábana tan grande

Que no la puede doblar

There is a man with so much money

He cannot count it

A woman with a bedspread so large

She cannot fold it

While one interpretation of the foregoing stanzas relate to “the coins of the Lord,” … and “the bedspread of his mother,” they also convey an important cultural legacy of New Mexico. In these stanzas Rudolfo Anaya, the first New Mexico Hispano to achieve national and global literary notoriety, not only relays one of his grandfather’s poetic riddles, but he reminds us about the historical sequence of the settler languages spoken in the American Southwest for at least 400 years now. While he affirms the cultures of the original native peoples of this region throughout his literary works, Anaya nevertheless establishes a cultural sequence that continues to challenge the mythology inherent in the lingering Manifest Destiny enterprise which attempted to erase his ancestors’ language and legitimacy in the United States.

In Anaya’s “The Magic of Words,” (1982) an essay based on a commemorative lecture delivered at the University of New Mexico’s (UNM) Zimmermann library, he begins with the two foregoing stanzas above to honor the oral tradition of his abuelitos (grandparents) and which also served to initiate and educate him about the world he was born in at Pastura, New Mexico. The stories his grandfather conveyed to the young people of this village included seeming unscientific accounts of the stars and the universe the First Nation peoples of the region were already well aware of; but, he writes, these “stories of the old people taught us to wonder and imagine” and later generated “a thirst for knowledge.”

In “The Magic of Words,” Anaya describes his early educational transition from a world of the familiar Spanish language his community mainly spoke into the English required in the public, nonsectarian, education system established in New Mexico during the early 20th century. He engages this transition with concern and some trepidation stating, “I, who was used to reading my oraciones (prayers) en Español…, I now stumbled from sound to word to groups of words, head throbbing” going “deeper into the maze of a new language.” Seeming echoes of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave can be discerned here; in this ancient Greek allegory, as many of you may recall, a former cave dweller begins his journey to personal enlightenment by leaving the comforts of a deep cavern wherein many cultural assumptions remained unquestioned. In the case of Anaya, he expands his cultural enlightenment, anchored in his native Pastura, by visiting a small library located up on the second floor of the fire station in Santa Rosa, New Mexico, where a public librarian would place many books in his hands to read.

As in Plato’s allegory, where once outside of the cave a guide appears to help the former cave dweller, Anaya’s new guide would be Ms. Pansy, the librarian in Santa Rosa. He writes that she “fed me books as any mother would nurture her child” and that this experience would hasten his move from the world of spoken words further into the world of books. For Anaya, new worlds existing out of the village of Pastura and Santa Rosa could be explored vicariously through literature; one of these new worlds would be an old city called Albuquerque, founded roughly 70 years before the American Revolution, where his education involving literary works would continue into higher levels. At Albuquerque High School, Anaya would develop his writing skills to assist some of his friends in conveying the love notes they could not craft themselves; he writes, “I wrote poetic love notes for a dime … and thus worked my way through high school. And so, a library is also a place where love begins.”

Anaya’s climb out of his familiar caves continued when his attention turned to higher education; he writes that after completing his high school education, he “wandered up the hill to enroll in the University of New Mexico.” The library at UNM offered him many more book stacks to explore than was possible in Santa Rosa. But, within these stacks he discovered, “A million million worlds. And the beauty of it is that each world is related to the next, as was taught to us by the old ones.” His occasional references back to the value of his ancestor’s dichos (sayings) echo what some of the Navajo and Hopi students at the University of New Mexico state to this day when conveying to others about the formal education they receive at the university; invariably, they will claim that their higher education was just as valuable as the wisdom imparted to them by their elders in their respective pueblos of New Mexico.

But what seems to be his most important discovery while exploring and researching within the library stacks of UNM’s Zimmerman Library was a seeming natural impulse to empathize for others. He affirms the importance of being open to the influence of our life guides, but he also asserts that others, like a first-generation college student, are climbing out of their own caves as well and requiring the attention that he had earlier received from Ms. Pansy in the Santa Rosa public library. He writes, “sometimes I get lost when I wander through it, and I cannot help but wonder if there are students around who are also lost. Is there someone who will guide them through this storehouse of knowledge?” It seems that, for Anaya at least, libraries and the magical words hidden in their books can serve to impart knowledge, facilitate love, and encourage empathy about others.

Reference: Anaya, Rudolfo A. “The Magic of Words: Rudolfo A. Anaya and His Writings.” Edited by Paul Vassallo. University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque, p. 9-18, 1982.

For more on Rudolfo Anaya’s “The Magic of Words,” attend Chaves’ talk, “Ever Changing, Ever Growing — Rediscovering The Magic of Words by Rudolfo Anaya.”

Saturday, June 8th, 2024.

Special Collections Library, Botts Hall, 423 Central Ave., Albuquerque, N.M. 87102

Click here for more information and to register.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

REFLECTIONS ON THE LOSS OF A NEW MEXICO CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER

By Carlyn N. Pinkins, M. A.

“The Dr. Harold Baileys of the world should inspire us all to do what we can to leave our communities, our towns and cities – our great state – better places than we found them. While we do our part to create the Dr. Harold Baileys of the future, we should also strive to make sure that the Dr. Harold Baileys of our past and present are never forgotten.”

RUDOLFO ANAYA: CATCHING CULTURES IN BLESS ME, ULTIMA

By Richard Wayne Etulain

Anaya greatly expands the cultural contributions of his novel by combining the usual (Bildungsroman—growing up theme) with the unusual (complex, diverse New Mexico Hispanic culture)…

UP BY OUR BOOTSTRAPS; TWO LIVES IN RETROSPECT

By Finnie Coleman

I found myself fascinated with Dr. McIver’s transition from the stultifying hopelessness of the Segregation Era to the wistful hopefulness of the Civil Rights Era…

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

CHRIS CHAVES

Chris Chaves works for the University of New Mexico, College of Arts & Sciences; he has years of experience creating and facilitating public humanities seminars involving the intersection of literature, ethics, and social justice. He completed a doctoral degree at the University of Southern California where he investigated the links between English and math courses, student involvement, and academic retention in community colleges. Aside from his administrative experiences, he has taught for the University of New Mexico, the College of William & Mary, Southern Illinois University, and lectured at Santa Fe Institute. He is a member of the Ralph Waldo Emerson Society.