ANCIENT DEATH RITUALS RUN DEEP IN NEW MEXICO

- By Ana Pacheco

- No Comments

Through the mid-20th century some women wore the tápalo in the villages of northern New Mexico. That tradition is long gone, but the one that remains is the descanso, the roadside memorial.

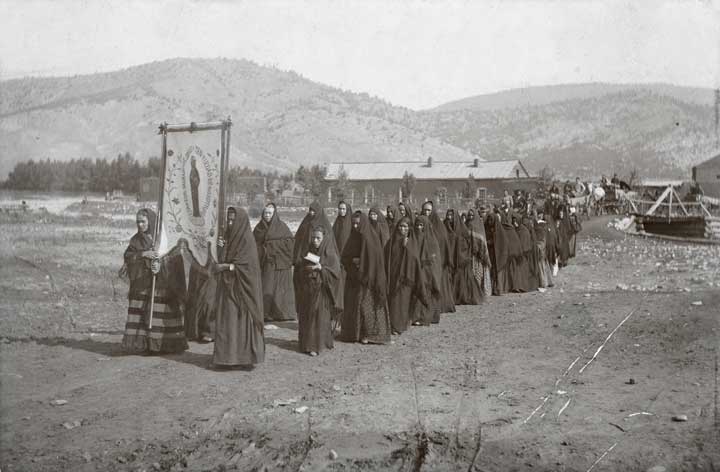

IMAGE: The black shawl, known as the tápalo, was a symbol of mourning widely worn by women in New Mexico from the 1600s through the mid-20th century. Photo John Candelario. Courtesy Palace of the Governors [NMHM/DCA]. No.0165857.

SHARE:

In my 2019 book, Death Rituals of New Mexico, I delved into the rituals and customs of caring for the dead in Hispanic New Mexico. In 1850 when New Mexico became a U.S. territory, its citizens began to adopt the funeral practices that were popular throughout the country. As quickly as these traditions evolved, two ancient customs remained constant. One pertained to the mourning shawl (tápalo) worn by Hispanic women through World War II that had roots in the longest war in recorded history. From 718 through 1492 AD, the Spanish and the Moors battled over territory and religious dominance. Through the mid-20th century some women wore the tápalo in the villages of northern New Mexico. That tradition is long gone, but the one that remains is the descanso, the roadside memorial.

Los Moros y Cristianos

The constant reminder of the death in the community was borne through fashion. The tápalo (black shawl) was the requisite garment for women to wear for one full year after the passing of a loved one. The vertical garment covered the body from head to ankle. It was yet another vestige that had been woven into the culture after several centuries of Moorish occupation in Spain that trickled down to the distant settlements of the empire. The tápalo is reminiscent of the hijab and burka worn by women in the Muslim world today. During this era in New Mexico the tápalo was such an important part of a person’s legacy that it was often listed in a person’s will to be handed down to the next woman in the family. It was also presented as a wedding gift by the groom to the bride so that she could wear the tápalo at the time of his death and for the preceding year. These black shawls were also worn by other women in the community when they went to express el pésame (condolences) to those who had lost a loved one. As these women donned their mourning attire they paid their respects with the traditional protocol, which included an emotional display by the widow of weeping and in a wailing tone of endearing remembrances for the deceased known as a requiebro (to lament the memory of the dead). The requiebro is also attributed to the Moorish custom of reciting dirges for the dead. The typical requiebro by a widow included: Ya tofuiste y me dejaste sola. ¿Que voy a hacer sin tí vida mía? Se nublara mi casa enternamente. (My house will be forevermore without light. What will I do without you, My Beloved? You’ve left me alone and desolate.)

Los Hermanos Penitentes

One aspect of the Hispanic death ritual in New Mexico that has gone unchanged is the descanso, the roadside memorial. Like the olive trees that cover the hills of southern Spain, descansos dot the landscape of New Mexico. A glimpse of these memorials as motorists zoom down the highway acts as a warning: slow down or become the next traffic fatality. Roadside memorials are all different, just like the people they commemorate. Some are more elaborate than others, along with the requisite cross they’re adorned with flowers, images of saints, photos and personal items that best describe the personality of the deceased.

The roadside crosses found along New Mexico byways and highways mark the spot where a life has ended tragically. This practice of placing crosses, laying stones or creating a devotional homage to the deceased is practiced by cultures around the world. With the increase of random acts of violence filling the nightly news with images of terror around the world this practice has morphed into a universal tradition, spontaneously marking the spot as a memorial with flowers, photos and candles for the dead.

In New Mexico these death markers are known as descansos from the Spanish tense decansar (to rest). The tradition of the descanso began with the 16th century confraternity, La Fraternidad Piadosa de Nuestro Padre Jesus Nazareno, also known as Los Hermanos Penitentes (the Brotherhood of the Repentant). The Penitentes placed crosses, or laid stones to mark the place of death for their fellow Spaniards who died along El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro (The Royal Road to the Interior). These remembrances were erected for the colonists who died of exposure or were killed by Indians along the treacherous 1,600–mile trade route that began in Mexico City and ended in San Gabriel in northern New Mexico. The descanso was a remembrance to the anima (soul) of the deceased. Las Cruces, the state’s largest city to the south, got its name from the crosses that were erected for the dead along that journey.

The increase of bicyclists on the road has led to the deaths of several people killed by motorists. The term Ghost Bikes is dedicated to remembrance of the fallen cyclist. Unlike the traditional descanso, which is usually a few feet from the ground, the Ghost Bike features a full-frame white replica of a bicycle making it highly visible on the highway. The memorial includes information about the person with personal objects adorning the bike frame. The Albuquerque City Council passed legislation for this type of descanso making it illegal to desecrate, deface, destroy or remove Ghost Bikes.

Author’s note: This blog was excerpted from my 2019 book, Death Rituals of New Mexico

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

CELLPHONES IN SCHOOLS: THE UNSPOKEN BROADER IMPLICATIONS

By Charity Darkwa

“This concludes that students treasure their social media interactions, games, and other cellphone activities over academics and intellectual pursuits.”

DOROTHY B. HUGHES: A FEMINIST ICON, AN ICON FOR WRITERS

By Monika Dziamka

“When the search gets tough, and the professional identity crisis again looms nigh, I remind myself of the extraordinary career of Dorothy B. Hughes, a woman, mother, and writer who helped solidify New Mexico’s literary legacy not just in the United States, but around the world as well.”

CULTURE ALSO COMES IN THROUGH THE KITCHEN

By Teresa Dovalpage

“Here in Hobbs, where I currently live, the Cuban community, very small when we moved here seven years ago, is growing fast.”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

ANA PACHECO

Ana Pacheco is a Santa Fe local, her family settled in the capital city in 1692. Pacheco was the City Historian in 2015–2017 and the author of eight books on Santa Fe and New Mexico history. She was the founding publisher and editor of La Herencia, a quarterly magazine on New Mexico history from 1994–2009. During her publishing career she has received numerous awards from organizations like PEN New Mexico and the National Association of Press Women. Since 2019, Pacheco has provided a two-hour historical walking tour of her beloved hometown called Santa Fe Revisited. To learn about Santa Fe’s fascinating history please visit her website: historyinsantafe.com