SHARE:

The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines democracy as a government by the people, especially the rule of the majority, and one that is characterized by free and open elections. As Americans, most of us tend to take our democratic rights for granted. We expect to have access to certain services, we expect to be able to vote how we would like, and we expect there to be avenues to schooling and education. Certainly I always took for granted having a pathway to learning, education and schooling, and most importantly, to books. With both of my parents being teachers, I was raised around books and grew up with the expectation that I’d be able to read anything I wanted, and so I did.

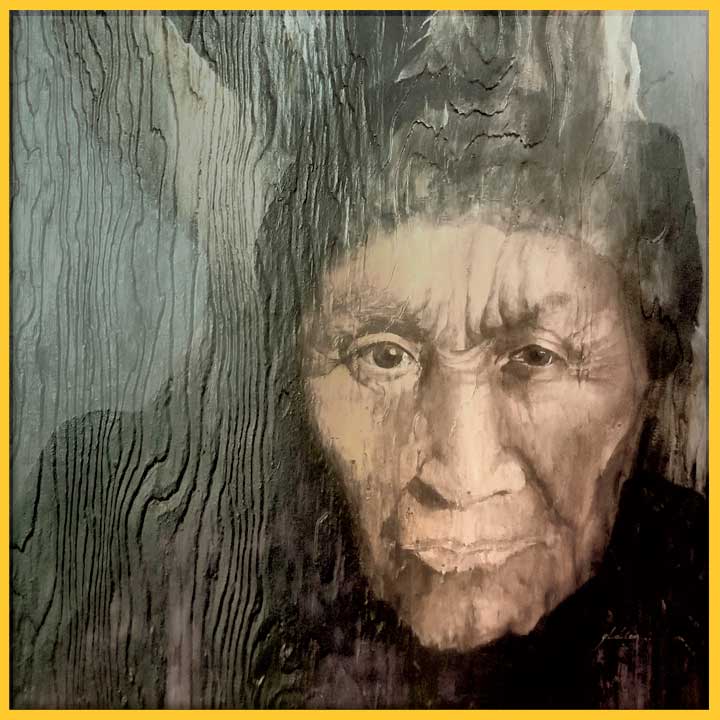

One of the first books I remember reading as a little girl was the classic coming-of-age story Bless Me, Última by author Rudolfo Anaya. The book tells the universal tale of a young boy Antonio, growing up in a small town in Northern New Mexico in the aftermath of World War II, who begins to question the beliefs and expectations of his traditional Catholic family. Antonio’s struggle to assimilate his growing curiosity and dissatisfaction with the world around him is facilitated by the old woman Última who comes to live with his family, who befriends him, and helps guide him on his journey of comprehending a world that is outside the assumptions and opinions of his parents.

Última is a curandera, a healer who has an affinity for plants, for herbs, and for what some would call magic. She is accompanied at all times by her owl, who is widely considered her familiar. The book itself is filled with the rich “Spanglish” language of New Mexico, and with beautiful imagery of harvests and apple trees, golden carp, school plays, friendship, and family. It is also filled with depictions of strife, betrayal, conflict, murder, burgeoning sexuality, foul language, and witchcraft. It is these three latter concepts that have been the basis and justification for banning this book several times and in numerous states over the past 30-plus years.

Unfortunately, attempts to ban books and to create legislation that allows for government restrictions on certain works of literature are neither new nor unexpected, both nationally and in our own state. In 1981, former state Sen. Christine Donisthorpe (R-San Juan), who was on the Bloomfield School Board, was among several school board members who called not only for a ban on Bless Me, Última but who actually burned the physical book. Anaya told the Albuquerque Journal that burning his book represented “extreme dictatorship.” When one considers past cultures and governments that also burned books, such as the Nazi Party of Germany in the 1930s, it is clear that the banning and destruction of books, and subsequent limiting of access to these same books, are hallmarks of dictatorship and the opposite of democracy.

Recently, Bless Me, Última has come under scrutiny in Oklahoma, where the state’s Attorney General is currently reviewing the book, among others, in response to complaints from individuals who claim the book is “obscene.” Other states where the book has previously been banned include Arizona, California, Texas, New York, Missouri, and according to the American Library Association’s website, Anaya’s masterpiece has appeared regularly on their annual lists of most banned books. Anaya himself was always quick to point out that each time his book was banned, the subsequent backlash against this censorship resulted in increased book sales, expanded requests by other libraries for copies of the book, and an overall heightened awareness and interest in Chicano culture and literature – the exact opposite of what book banning attempts aim to accomplish.

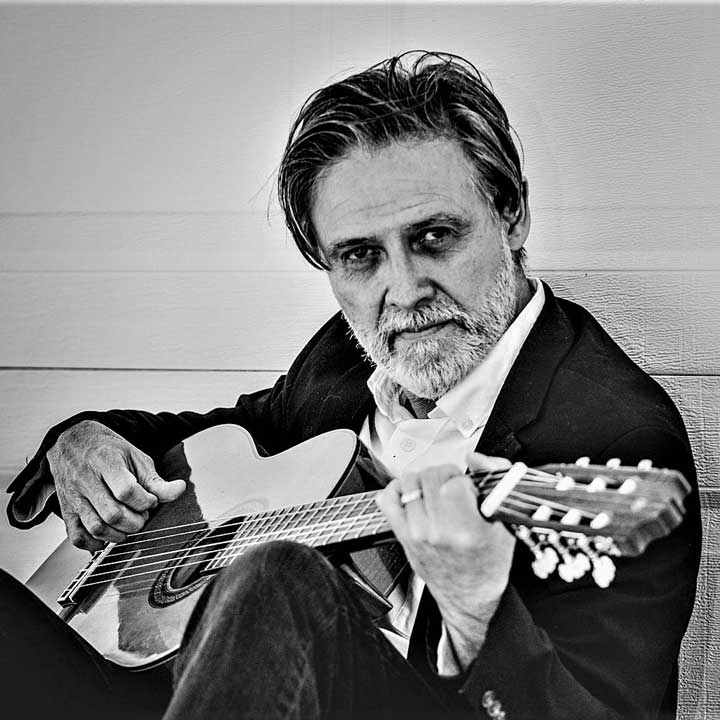

Anaya, whose career as a teacher preceded his fame as an author, was a staunch supporter of freedom of speech, education, and equality; and he fought back against censorship in numerous ways during his lifetime. He donated many copies of Bless Me, Última and his other books to schools throughout New Mexico and in other states. Many of his other works represented and advocated for freedom of speech. Memorably, he hosted the Librotraficante Caravan at his home as part of its tour in 2012. The Caravan was an initiative started by a Houston-based nonprofit group called Nuestra Palabra, whose aim was to run contraband books that had been banned in Arizona, back into the state. The Caravan stopped in Albuquerque on its way to Arizona, and Anaya’s niece Belinda Henry vividly remembers the day Librotraficante, as well as many local writers, teachers, poets, and community advocates took over her uncle’s house, celebrating free speech with food, wine and margaritas, music, poetry readings, and “this overwhelming sense of joy” that works of banned literature were being returned to where they had previously been restricted and demonized.

June 28 marks two years since Anaya, widely regarded as the Godfather of Chicano literature, died. This year also marks the 50th anniversary of the publication of Bless Me, Última. This book, which catapulted him and his beloved New Mexico to worldwide acclaim, has been translated into at least 10 languages and is widely considered one of the seminal literary works depicting the Mexican-American/Latino/Chicano experience. I discovered this book when I was 10 years old, finding it in my father’s car and devouring it in one sitting. It’s hard to describe just how much this book has meant to me, representing as it did a way of life in New Mexico that was so familiar and yet one that I had never experienced in a book, much less a novel that was widely published and acclaimed. Growing up in the mid-1980s, the majority of literature I was exposed to portrayed a limited aspect of American culture. There were few books I knew of that were set in our state, which depicted characters with the same background, language or culture as mine, or that simply represented the collective experience of growing up New Mexican. I fell in love with the book that day, and in later years, was fortunate and honored to become dear friends with “Rudy,” as he was lovingly called. He made me not only a better writer and more aware of the inequities around me, he made me into a better human being.

Ultimately, Anaya was not only a world-renowned author, poet and teacher who gave us the gift of Última; he also was a voice for tolerance, for inclusion, for equality, for human rights, for freedom of speech, and for democracy for us all. Gracias por todo, Rudy, y descanse en poder.

This column was generously funded by a grant from the Mellon Foundation to explore the question of Democracy and the Informed Citizen.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

NEW MEXICO’S AMAZING BLACK HISTORY

By Rob Martinez, State Historian of New Mexico.

“African history runs deep in New Mexico. Black history is often framed within the institution of slavery, but in New Mexico, New Mexicans of African descent were ambassadors, explorers, colonists, soldiers, cowboys, discoverers, settlers, businessmen, educators, and much more.”

SCANNING FOR STORIES

It was a Friday afternoon in November and I was driving on a state road through the hills of the Mimbres Valley. The entire landscape was bathed in a golden hue because the tree leaves had made their full conversion to a bright yellow color just before falling off the branches.

REFLECTIONS ON THE LOSS OF A NEW MEXICO CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER

By Carlyn N. Pinkins, M. A.

“The Dr. Harold Baileys of the world should inspire us all to do what we can to leave our communities, our towns and cities – our great state – better places than we found them. While we do our part to create the Dr. Harold Baileys of the future, we should also strive to make sure that the Dr. Harold Baileys of our past and present are never forgotten.”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

VANESSA BACA

Vanessa Baca is a cook, writer, public relations professional, blogger and podcaster. Her food blog: www.foodinbooks.com, reviews various works of literature and recreates the food references in these books. Her podcast: www.anchor.fm./cookingthebooks, showcases literary cuisine with a variety of guests. She is a native New Mexican, lived briefly in Spain, travels extensively, and has taken cooking lessons in several countries.