CELEBRATING THE DEAD: DÍA DE LOS MUERTOS AND ALL HALLOWE'EN

Many people do not know the origins of this fun – and fright-filled night, nor of the similarities its origins share with Día de los Muertos.

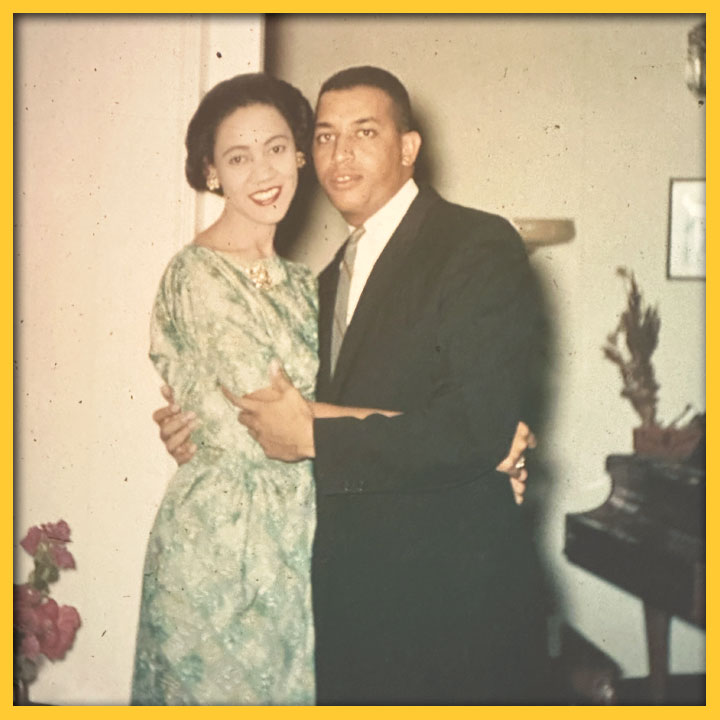

PHOTO CAPTION: Image of the author’s personal altar. In the center is a drawing of the author’s sister Christel Angélica Chávez, Captain US Air Force. Drawing by Anthony Thielen (cousin). Photo courtesy of Nicolasa Chávez.

SHARE:

Autumn is truly special in New Mexico. The mesmerizing scent of roasted green chile permeates the air, the leaves of aspens and the setting sun fill our landscape with a spectacular golden glow, and red chile ristras adorn portals and porches drying for the coming winter season. Local feast days and celebrations herald the coming of the new season.

Along with seasonal traditions and changes in the air, New Mexicans joyfully anticipate Halloween and Día de los Muertos. In the grand scheme of New Mexican history, both holidays are relatively new to New Mexico, Día de los Muertos more so than Halloween. Although neither was a traditional celebration during colonial times, both have been widely embraced and are now a part of our shared celebrations. They have also mixed with our own local lore, the story of La Llorona, for example, is a popular seasonal favorite.

Similar to News Mexico’s own tri-cultural myth, which only recognizes three cultures in New Mexico, these holidays are also misinterpreted to represent only one individual culture, rather than developing from a blending of various cultures throughout the years. However, if one digs into the history and origins of each holiday one can learn of a history not that different from ours here in New Mexico. One learns of a history in which many cultures and traditions, not only a select few, combined to pave the way for our contemporary celebrations today.

In the case of Día de los Muertos, one acknowledges and embraces the “Mexican” version of the holiday even though Muertos ceremonies manifest differently in each region or town throughout the Americas, much like Feast days in New Mexico are unique to a particular Pueblo or Hispano village. In the case of Halloween, the tendency is to assert that it is of a more general “Anglo”, or “U.S” heritage. This larger grouping of people is the third group in the New Mexican tri-cultural myth and mistakenly thought to be without cultural tradition at all. The general perception is these two holidays have nothing in common with each other. It is very common to hear “I wish the American Halloween were more like Día de los Muertos” or “I wish the American Halloween honored the departed.” Many people do not know the origins of this fun- and fright-filled night, nor of the similarities its’ origins share with Día de los Muertos.

Both developed from early pre-Christian ceremonies that honored the departed, and both are products of years of assimilation between pre-Christian and the Roman Catholic cultures. Even though these are the two I focus on here, it is important to note that every culture around the world has or at one time had a day of remembrance for the holy departed.

In the historic lands of present-day Scotland and Ireland, the Romans encountered ancient traditions honoring the dead. Referred to as Samhain, the ceremonies coincided with the shortening days and the darker half of the year. The Celtic tribes celebrated the return of the departed by placing offerings of food and drinks, ancestors honored with storytelling and song. When the Romans spread out in a quest to conquer the European continent, they encountered and learned about these celebrations. The earliest date on the Roman Catholic calendar to honor the departed was established in 609 CE by Pope Boniface IV. The date moved several times, eventually falling at the same time of year as the ancient Samhain traditions. Pope Gregory II solidified Nov. 1 as All Saint’s Day during the middle of the ninth century. The observance of All Souls on Nov. 2, standardized by St. Odlio, the fifth Benedictine Abbot of Cluny, in the 10th century was to honor those who had not entered sainthood, in effect to Christianize these popular celebrations. The European Feast of All Souls, or All Hallows, often included a special Mass, visiting cemeteries, lighting candles and placing flowers on graves. Families left out soul cakes and other foods for the departed. Soon the eve of All Hallows, on Oct. 31, came to be called Hallowe’en, or Halloween.

By the time the Spanish arrived in Mexico they were accustomed to celebrating the feast days of All Saints’ and All Souls’ Days (along with the Eve of All Hallows on Oct. 31). Upon arrival in what is present-day Mexico, they witnessed Indigenous ceremonies honoring the dead. One of the earliest historical written records of these events is that of Fray Diego Durán at the end of the 16th century. Aztec ceremonies took place around the time of the early harvest in August. After the arrival of the Spanish, the ceremonies moved to Oct. 31, Nov. 1 and 2. The pre-Columbian and Catholic ceremonies combined, making the holiday the one we know today.

The Mexican celebration is the most famous with its bright, colorful and joyful celebration. Brilliant marigolds and gladiolas adorn the ornate ofrendas in Mexican homes. The scents from the kitchen fill the air with mole, tamales, chocolate and baked pan de los muertos (bread of the dead). Families attend Mass and then visit gravesites with candles and flowers. Merrymaking, parades of bands called comparsas, and people dressed in calavera (skull) makeup and costume to honor the departed play music and dance all night.

In colonial New Mexico only the tradition of holding a Mass for the departed continued. Early Samhain traditions such as the wearing of masks and the banging of pots and pans to ward off evil spirits and the carving of turnips and other root vegetables would turn into the carving of jack-o’-lanterns in the U.S. and the blowing of noisemakers on New Year’s Eve. The tradition of mummers’ plays and traveling from door to door to entertain for food and drink became today’s trick-or-treating. The tradition of going door to door continued in colonial New Mexico with the traditions of Las Posadas at Christmas and Los Días at New Year’s, but trick-or-treating on Halloween did not arrive in New Mexico until the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The celebration of Día de los Muertos came much later toward the end of the 20th century.

Today Halloween is a national holiday in Ireland and Scotland. People take time off work and school, allowing time for families to come together and celebrate just. Días de los Muertos is an official holiday that takes place over several days. A curiosity today is the rise in popularity of the U.S. Halloween in Mexico as the Mexican Día de los Muertos grows in popularity each year in the U.S. These ceremonies share joy, revelry and uplifting of the spirit for once again we can visit with loved ones past. We can honor a mix of cultures as we honor these traditions. Every year I roast and puree my own pumpkin; I make pumpkin soup, bread and cookies. At home, I make red chile sauce and cook like a fiend with freshly roasted green. I honor my departed loved ones by adorning my family altar with marigolds, candles, squash and seasonal decorations. I open my door for trick-or-treaters in the spirit of the mummers’ plays of old, and if leaving the house for the evening I leave pan de los muertos or pumpkin cookies as an offering for my ancestors.

This column was funded in part by a generous grant from the McCune Foundation.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

REFLECTIONS ON THE LOSS OF A NEW MEXICO CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER

By Carlyn N. Pinkins, M. A.

“The Dr. Harold Baileys of the world should inspire us all to do what we can to leave our communities, our towns and cities – our great state – better places than we found them. While we do our part to create the Dr. Harold Baileys of the future, we should also strive to make sure that the Dr. Harold Baileys of our past and present are never forgotten.”

RUDOLFO ANAYA: CATCHING CULTURES IN BLESS ME, ULTIMA

By Richard Wayne Etulain

Anaya greatly expands the cultural contributions of his novel by combining the usual (Bildungsroman—growing up theme) with the unusual (complex, diverse New Mexico Hispanic culture)…

UP BY OUR BOOTSTRAPS; TWO LIVES IN RETROSPECT

By Finnie Coleman

I found myself fascinated with Dr. McIver’s transition from the stultifying hopelessness of the Segregation Era to the wistful hopefulness of the Civil Rights Era…

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

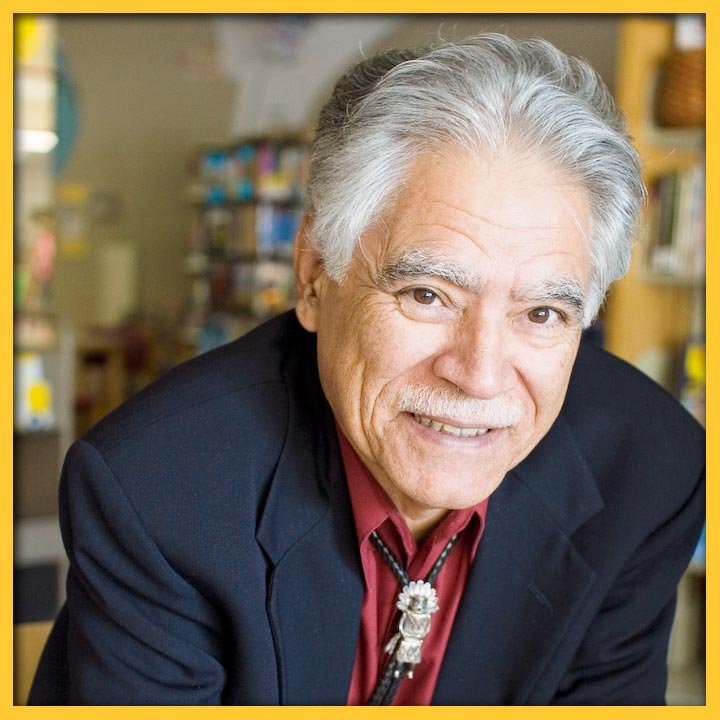

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

NICOLASA CHÁVEZ

Nicolasa Chávez, a fourteenth generation New Mexican, is a historian, curator and performance artist, whose work concentrates on the rich multicultural heritage of New Mexico and the connection between New Mexico and the Spanish speaking world. Her exhibitions include New World Cuisine: the Histories of Chocolate, Mate y Más, The Red that Colored the World, Flamenco: From Spain to New Mexico, and Música Buena: Hispano Folk Music of New Mexico. She was an invited guest curator at the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art in Kanazawa, Japan, for the exhibition Possibility of the Crafts: The Third Triennial of Kogei, which highlighted the traditional arts of New Mexico. She is a contributing author to the publication A Red Like No Other: How Cochineal Colored the World (Skira Rizzoli Press) and the author of The Spirit of Flamenco: From Spain to New Mexico (Museum of New Mexico Press) and A Century of Masters: the NEA National Heritage Fellows of New Mexico (LPD Press) which won a New Mexico Book Award. She performs and conducts lecture/demonstrations on the history of Flamenco, Spanish Dance, and Argentine Tango and currently serves as the Deputy State Historian for our great state of New Mexico.