SHARE:

My friend Laura X, founder of the Women’s History Library, sends me two and three notices a day about film screenings. A multitask-juggler of scores of feminist concerns, it is difficult for me to keep up. Which e-mails do I open and pay attention to? One I did open just the other day unfolded a gem: Cinema Sabaya. It is the first feature dramatic film by Israeli filmmaker, Orit Fouks Rotem. She has translated her community-based film teaching experiences with women in several locales on both sides of the Middle East conflict into a cultural filmic story of how motion pictures can create allies. And enlarge our worlds.

I know something about community-based

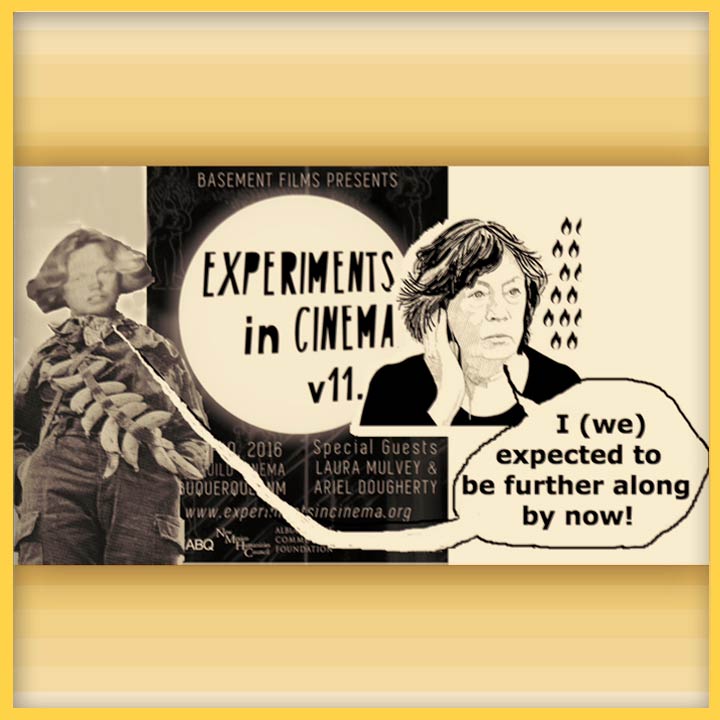

With funding from the New Mexico Humanities Council and the Devasthali Family Foundation I am holding a series of screenings throughout New Mexico this spring. Each program will vary as I present the philosophy, tempo and nature of WMM films with a different selection of works at each screening and lead audience discussions. New in the mix will be a handful of more contemporary films from present-day girl-centered

For more information about these NMHC grant support public programs, please contact Ariel Dougherty at arielcamera@gmail.com.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

REFLECTIONS ON THE LOSS OF A NEW MEXICO CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER

By Carlyn N. Pinkins, M. A.

“The Dr. Harold Baileys of the world should inspire us all to do what we can to leave our communities, our towns and cities – our great state – better places than we found them. While we do our part to create the Dr. Harold Baileys of the future, we should also strive to make sure that the Dr. Harold Baileys of our past and present are never forgotten.”

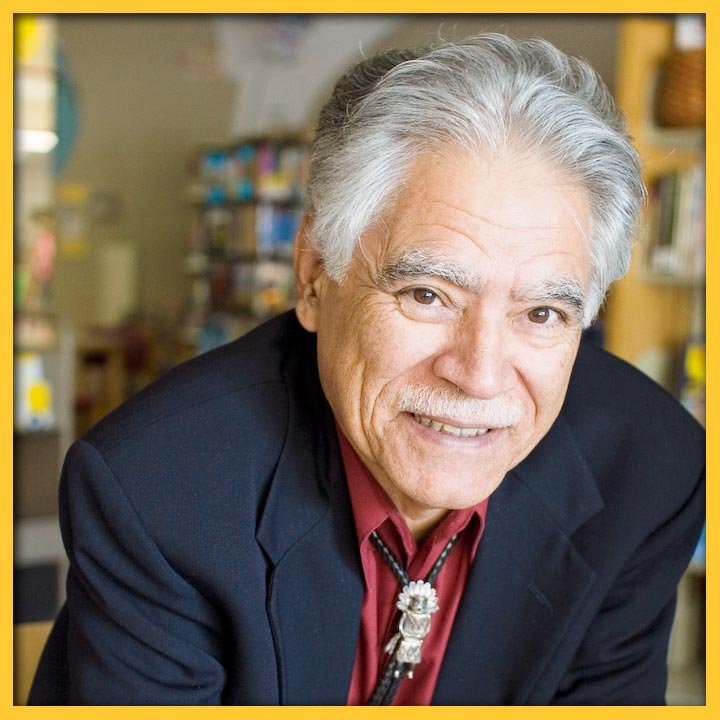

RUDOLFO ANAYA: CATCHING CULTURES IN BLESS ME, ULTIMA

By Richard Wayne Etulain

Anaya greatly expands the cultural contributions of his novel by combining the usual (Bildungsroman—growing up theme) with the unusual (complex, diverse New Mexico Hispanic culture)…

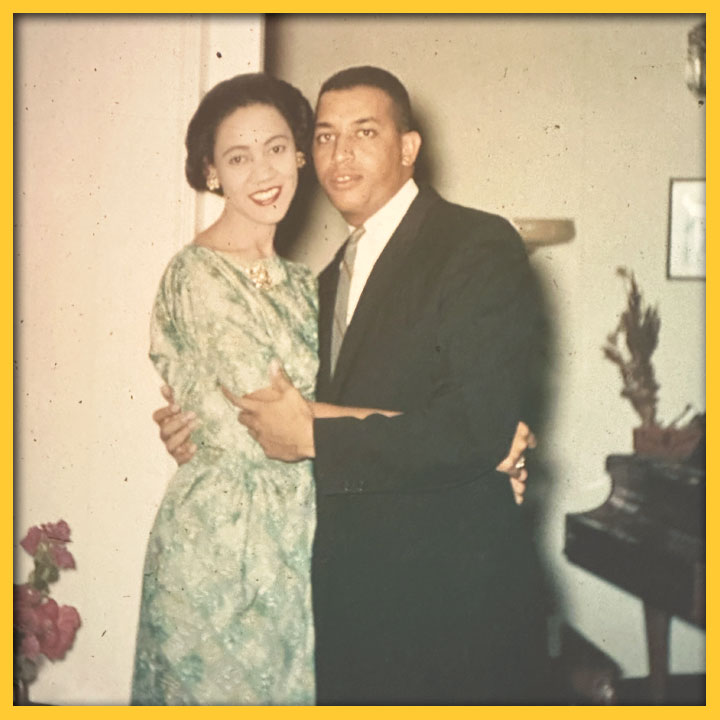

UP BY OUR BOOTSTRAPS; TWO LIVES IN RETROSPECT

By Finnie Coleman

I found myself fascinated with Dr. McIver’s transition from the stultifying hopelessness of the Segregation Era to the wistful hopefulness of the Civil Rights Era…

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

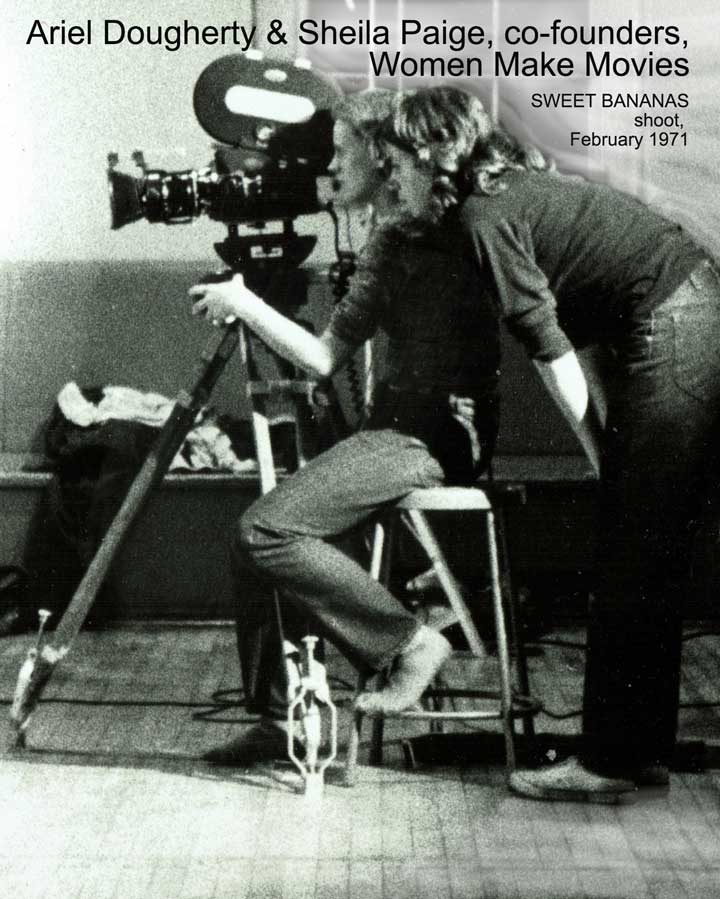

ARIEL DOUGHERTY

Independent filmmaker and feminist cultural advocate, for over five decades Ariel Dougherty has been a leader in the building of women identified cultural organizations and one of their primary tasks, teaching strong woman centered arts to women and girls. In 2022 she is celebrating her work as a co-founder of Women Make Movies, Inc., today the globe's largest distributor of women's films.