SHARE:

Food is one of the most tangible elements of culture. Traditional dishes, with their particular ways of preparing them, are passed down from generation to generation and can act as symbols of national, ethnic, regional and family identity. According to Claude Fischler, “Food is central to our sense of identity. The way any given human group eats helps it assert its diversity, hierarchy and organization, but also, at the same time, both its oneness and the otherness of whoever eats differently” (Fischler 1988).

Popular speech reflects the importance of food as well. El amor entra por la cocina (love comes in through the kitchen) is a common Spanish saying. I guess the English equivalent would be “the way to a man’s (or woman’s) heart is through his/ her stomach.”

But, of course, it’s not just love that comes in through the kitchen, but also culture and individual uniqueness.

When I moved to Albuquerque in 2002 to attend the University of New Mexico, there was no established Cuban community in the city. There were isolated groups of Cubans, like the Pedro Panes, who had arrived as children in the `60s, and the rafters who came in ‘94. There was even a salsa band, Son Como Son, but no common spaces where Cubans gathered, no Cuban stores or botánicas, nor, sadly, Cuban restaurants. Cuban food as such was virtually unknown.

One day, when I was a graduate student in the Spanish and Portuguese Department, my classmates organized an international luncheon. I offered to bring

ropa vieja and moros y cristianos.

“Girl, what’s that about using old clothes in food?” a friend asked me, laughing.

I explained to her that Cuban ropa vieja is made with shredded meat fried in tomato sauce with garlic, onion, olives, pepper and salt. It’s often served with moros y cristianos (white rice and black beans cooked together so that the rice takes on a dark color). My dish was a complete success and gave me the opportunity to talk about the cultural diversity of our cuisine. I later described the same dish in

my novel Death Comes in through the Kitchen which, by the way, includes authentic Cuban recipes:

“The white rice represents the Spaniards while the black beans symbolize the dark-skinned Moors that settled on the shores of the Guadalquivir River,” read a description of the dish, typed on the menu in English, Spanish and French. “They merged their bloodlines and gave birth to a new race that changed the history of the Iberian Peninsula. Our moros y cristianos retain the best of the two ingredients, condensing them in a multicultural dish.”

CHILE, MOTHER OF FLAVORS

Cultural exchange through food has spread due to globalization. Sidney Mintz, the father of food anthropology, points out how the world’s cuisines have evolved because of the widespread interactions between cultures (Mintz, 1985).

On a personal level, I can attest that this interaction happens in the most common daily life situations. In 2008, my husband and I moved to Taos. I had a radio program on KNCE called “Música y Libros” where I talked about music, literature, community events and un poco de todo, a little bit of everything. Once, I happened to mention the recipe for Cuban-style chicken and rice, cooked together in the same pot. Several listeners called in to suggest that I add chile because “chile is the mother of all flavors.”

The next time I cooked rice and chicken, I added a couple of heaping spoonfuls of green chile to it. The result? There wasn’t even a bit left for the dogs. My husband — and everyone else who later tried it — said that Cuban-style chicken and rice with a New Mexican twist was the best ever. Since then, I haven’t stopped adding chile every time I make arroz con pollo, and nobody has yet complained.

CUBAN TEX-MEX

Here in Hobbs, where I currently live, the Cuban community, very small when we moved here seven years ago, is growing fast. Many come from central Cuba, especially from Cienfuegos and Villa Clara, and have brought, of course, their favorite dishes. There is even a Cuban shop called Dreke’s Market.

The newly arrived Cubans have blended easily with the Mexican, Texan and borderland communities. Culinarily speaking, they all have created a fusion cuisine that I like to call “Cuban Tex-Mex.”

Tamales are a good example. In Mexican cuisine, the use of corn dates to pre-Columbian civilizations (Pilcher, 1998) and tamales are very popular. They are popular in Cuba as well. But, while Mexican tamales are made with masa-harina or nixtamalized corn, Cuban tamales are made with fresh grated corn. They are, so to speak, cousins. As the two cultures come together, it is now common to find here tamales made with fresh corn filled with green or red chile — or both. They are spicy and delicious.

Food is much more than a means of sustenance; it reflects our cultural identity and is also a key component in social construction. Coming in through the kitchen, it’s possible to learn more about a culture than if we just sit politely in the living room.

REFERENCES

Dovalpage, T. (2018). Death Comes in Through the Kitchen. Soho Press.

Fischler, C. (1988). Food, self and identity. Social Science Information, 27(2), 275-292.

Mintz, S. (1985). Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History. Penguin Books.

Pilcher, J. M. (1998). Que vivan los tamales: Food and the Making of Mexican Identity. University of New Mexico Press.

LA CULTURA TAMBIÉN ENTRA POR LA COCINA

La comida es uno de los elementos más tangibles de la cultura. Los platos tradicionales, con sus modos particulares de prepararse, se transmiten de una generación a otra y pueden actuar como símbolos de pertenencia nacional, étnica, regional y familiar. Según Claude Fischler “La comida es esencial para nuestro sentido de identidad. La manera en que cada grupo humano come lo ayuda a reafirmar su diversidad, jerarquía y organización, pero también, al mismo tiempo, tanto su calidad de único como la otredad de aquellos que comen de forma diferente.” (Fischler 1988).

Por su parte, el habla popular refleja la importancia de la comida en refranes como “El amor entra por la cocina.” Pero, desde luego por la cocina no entra solo el amor, sino también la cultura, la gracia y la sandunga de cada cual.

Cuando me mudé a Albuquerque en 2002 para asistir a la Universidad de Nuevo México, no había una comunidad cubana establecida en la ciudad. Sí existían varios grupos de cubanos, como los Pedro Panes, que habían llegado en los años sesenta, los balseros que arribaron en el 94 y hasta una banda de salsa, Son Como Son. Pero no había espacios comunes donde se reunieran los cubanos, ni tiendas cubanas ni botánicas, ni (¡ay!) restaurantes cubanos. La comida cubana como tal prácticamente no se conocía.

Un día, siendo estudiante de postgrado en el Departamento de Español y Portugués, se organizó un almuerzo internacional entre mis compañeros. Yo prometí llevar ropa vieja y moros y cristianos

—Muchacha, ¿qué es eso de poner ropa usada en la comida? —me preguntó una amiga, muerta de la risa.

Le expliqué que la “ropa vieja” cubana consistía en carne deshebrada y luego frita en salsa de tomate con ajo, cebolla, aceitunas, pimienta y sal. Se sirve generalmente con moros y cristianos (arroz blanco y frijoles negros, cocinados juntos de manera que el arroz tome un color oscuro). Mi platillo fue todo un éxito y me dio la oportunidad para hablar sobre la diversidad cultural de nuestra cocina. Así la describí más tarde en mi novela La muerte entra por la cocina que, por cierto, incluye recetas cubanas auténticas:

El arroz blanco representa a los españoles y los frijoles negros a los moros que se asentaron en las orillas del Guadalquivir. Al unir su herencia de siglos, dieron origen a una nueva raza que cambió la historia de la Península Ibérica. Nuestros moros y cristianos contienen lo mejor de ambos ingredientes, condensándolos en un plato tan orgullosamente cubano como multicultural.

EL CHILE, MADRE DE SABORES

El intercambio cultural por medio de la comida se ha intensificado debido a la globalización. Sidney Mintz, padre de la antropología culinaria, señala que las cocinas del mundo han evolucionado como respuesta a las interacciones entre culturas (Mintz, 1985).

A nivel personal, puedo atestiguar que estas interacciones ocurren en las situaciones más simples del diario vivir. En 2008 mi marido y yo nos mudamos a Taos. Yo tenía un programa de radio en KNCE llamado Música y Libros donde hablaba un poco de todo. En una ocasión mencioné la receta del arroz con pollo estilo cubano, que consiste en cocinar todo junto en el mismo caldero. Pues me llamaron varios oyentes a sugerir que le echara chile porque “el chile es la madre de todos los sabores.”

La próxima vez que hice arroz con pollo añadí un par de cucharadas bien llenas de chile verde. ¿El resultado? No quedó ni un poquito para los perros. Mi marido —y todo el que probó aquel plato después— salió diciendo que el arroz con pollo al estilo nuevo mexicano era lo máximo. Desde entonces no he dejado de añadirle chile cada vez que lo cocino y nadie se ha quejado.

TEX-MEX A LA CUBANA

Aquí en Hobbs, donde vivo actualmente, la comunidad cubana, muy pequeña cuando llegamos hace siete años, crece a pasos agigantados. Muchos de mis compatriotas provienen de la zona central de Cuba, especialmente de Cienfuegos y Villa Clara, y han traído, desde luego, sus platos preferidos. Tan es así que hasta tenemos una tienda de productos cubanos llamada Dreke’s Market.

Los cubanos recién llegados se han integrado perfectamente con las comunidades mexicana, de la frontera y tejana. Culinariamente hablando, han creado una verdadera fusión que bien podríamos llamar “Tex Mex a la cubana.”

Los tamales son un buen ejemplo. En la comida mexicana, el uso del maíz se remonta a las civilizaciones precolombinas (Pilcher, 1998) y los tamales son muy populares. También lo son en Cuba. Pero, mientras que los tamales mexicanos se hacen a base de masa-harina o nixtamalizado, los cubanos usan maíz tierno rallado. Son, como si dijéramos, primos. Al encontrarse las dos culturas, es común encontrar ahora tamales de maíz tierno rellenos con chile verde y rojo—o los dos. Son picantes y sabrosísimos.

La comida es mucho más que un medio de subsistencia; refleja nuestra identidad cultural y es un componente vital en la construcción social. Al entrar por la cocina, es posible conocer más sobre una cultura que si nos sentamos muy cortésmente en la sala.

REFERENCIAS

Dovalpage, T. (2018). Death Comes in Through the Kitchen. Soho Press.

Fischler, C. (1988). Food, self and identity. Social Science Information, 27(2), 275-292.

Mintz, S. (1985). Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History. Penguin Books.

Pilcher, J. M. (1998). Que vivan los tamales: Food and the Making of Mexican Identity. University of New Mexico Press.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

NEW MEXICO’S AMAZING BLACK HISTORY

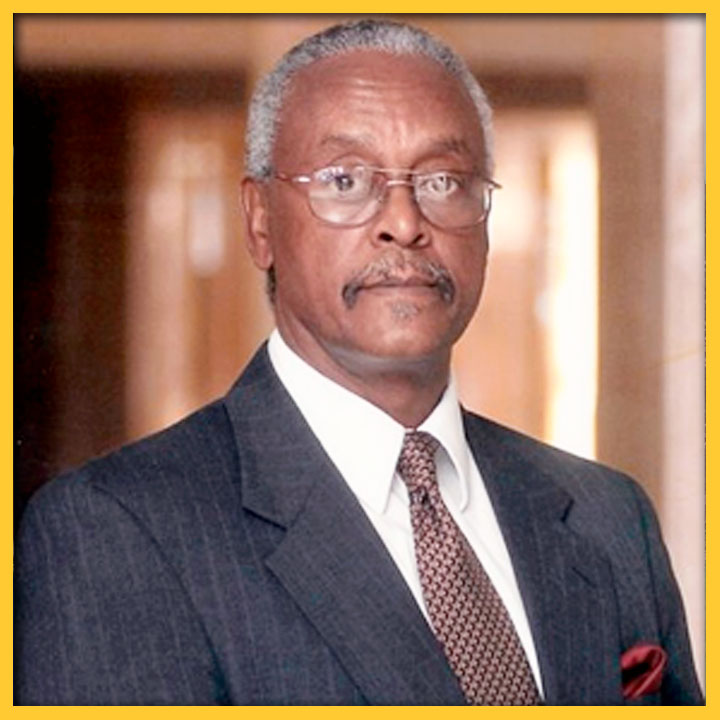

By Rob Martinez, State Historian of New Mexico.

“African history runs deep in New Mexico. Black history is often framed within the institution of slavery, but in New Mexico, New Mexicans of African descent were ambassadors, explorers, colonists, soldiers, cowboys, discoverers, settlers, businessmen, educators, and much more.”

SCANNING FOR STORIES

It was a Friday afternoon in November and I was driving on a state road through the hills of the Mimbres Valley. The entire landscape was bathed in a golden hue because the tree leaves had made their full conversion to a bright yellow color just before falling off the branches.

REFLECTIONS ON THE LOSS OF A NEW MEXICO CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER

By Carlyn N. Pinkins, M. A.

“The Dr. Harold Baileys of the world should inspire us all to do what we can to leave our communities, our towns and cities – our great state – better places than we found them. While we do our part to create the Dr. Harold Baileys of the future, we should also strive to make sure that the Dr. Harold Baileys of our past and present are never forgotten.”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

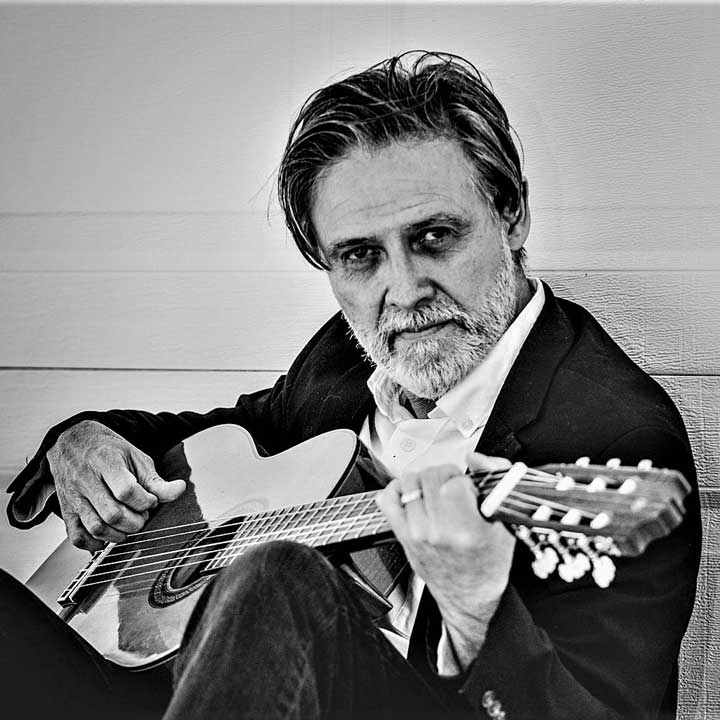

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

TERESA DOVALPAGE

Writer, translator and college professor, Teresa Dovalpage is a Cuban transplant firmly rooted in New Mexico. She is the author of thirteen novels, among them the Havana Mystery series, four short story collections and four theater plays. She lives with her husband, one dog and too many barn cats. Her blog is https://teredovalpage.com.