SHARE:

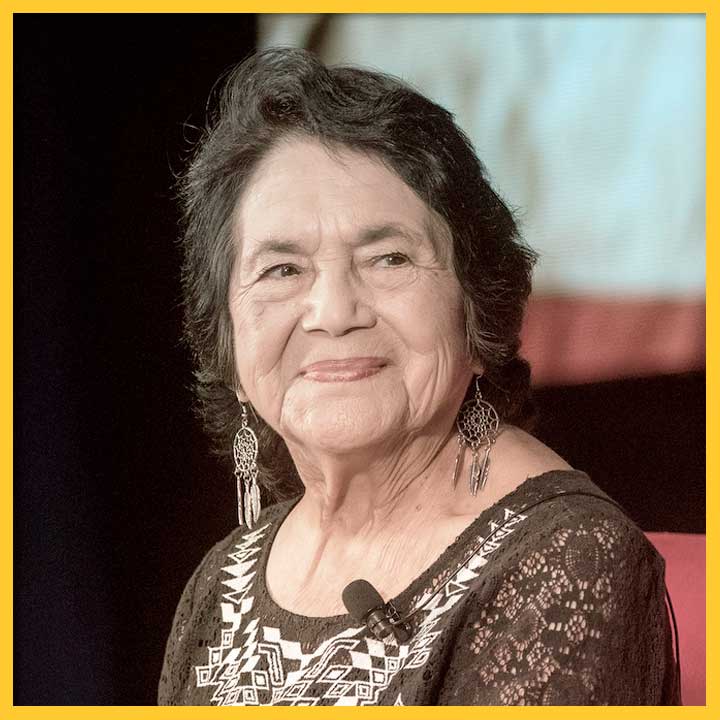

One of the most insulting insinuations made about women is that we are not meant to lead. As a little girl, I almost bought into this lie after hearing male names of leaders pertaining to my Mexican-American history time and time again — Pancho Villa, Emiliano Zapata, Cesar Chavez. It wasn’t until 2017 when I began my studies at the University of New Mexico that I began to learn of the incredible contributions that hundreds, if not thousands, of mujeres poderosas have made to Chicanx/Latinx/Mexican-American communities throughout history. The leadership, advocacy, and action displayed by none other than Dolores Huerta are clear evidence of a woman’s natural right to lead.

Unlike the existing assumptions that have circulated, Dolores Huerta is anything but the shadow of Cesar Chavez. On April 10, 1930, Dolores Clara Fernández Huerta was born in the small mining town of Dawson in northeastern New Mexico to hardworking parents, Alicia and Juan Fernández. Eventually, her parents divorced, and she moved west to California with her mother and two brothers where Alicia’s entrepreneurial spirit took flight. It was in Stockton’s culturally diverse and agricultural community where Alicia managed a hotel at affordable rates for low-wage workers, was involved in various community endeavors such as civic organizations and the church, and ultimately helped to shape Dolores’ feminism. Dolores grew up to be as active as her mother and eventually attended the University of Pacific’s Delta College in Stockton, earning her provisional teaching credential.

It was within the educational institution, however, where Dolores faced separate trials as both student and educator. During one instance in school, she faced racial discrimination when a schoolteacher, prejudiced against Hispanics, accused Huerta of cheating because her papers were too well-written. Later, as an educator, it is assumed that her economic justice activism was inspired by seeing her students come to school hungry and in bare feet. Only Huerta can tell us how much more discrimination she herself faced and witnessed, but what history has unequivocally demonstrated is that creating change is in her blood.

The slogan, “Sí se puede,” which has been widely used since the Chicano Civil Rights Movement, was originally coined by Dolores Huerta — one which has far too long been credited to the men of the movement. These words seem to have always been at the forefront of Huerta’s mind, especially given the number of organizations that she has founded and led in various leadership capacities. Some of these feats include co-founding and serving as leader of Stockton Community Service Organization; founding the Agricultural Workers Association; co-founding the National Farm Workers Association in 1962, which three years later formed into the United Farm Workers’ Union; and securing Aid for Dependent Families and disability insurance for farm workers in California in 1963. Huerta was also instrumental in the implementation of the Agricultural Labor Relations Act of 1975, she directed the first National Boycott of California Table Grapes, and is founder and director of the Dolores Huerta Foundation.

However, while Huerta has made tremendous social and political impacts on a transnational level, she has not been able to escape her own share of dolores, or pains, throughout her life for her intersectional identity as mujer, Chicana, mother, activist, etc. At 58, Dolores was assaulted while protesting the policies of then-presidential candidate George H. W. Bush in San Francisco. An officer with a baton broke four of her ribs and shattered her spleen. Once news got out, public outrage resulted in policy changes regarding crowd control and police discipline. Though it was a lengthy recovery for Huerta, she later took a leave of absence from the union to focus on women’s rights. As a Latina woman, she has faced sociocultural and gender expectations. In 1965, while Huerta was the leading organizer during the grape workers strike, she faced violence and sexism from growers she was staring down and their political allies, as well as some from within her own organization. In addition, Huerta married twice and had a relationship with Cesar Chavez’s brother Richard. She is the mother of 11 children and has many grand- and great-grandchildren who also have dedicated themselves to public service. As such, not filling the traditional role of stay-at-home mother has earned her criticism from traditional, conservative folks. Sin embargo, Huerta has clearly never herself become affected by the haters — her recognitions set the record straight.

Huerta’s passion for societal change has never limited itself to the support of just one community, earning her transnational forms of recognition. In the U.S., she has received the Eleanor Roosevelt Human Rights Award in 1998, the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2012, and is a two-time U.S. Presidential Award Recipient. She is a U.S. Department of Labor Hall of Honor inductee, and was the first Latina inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame. Additionally, the Mexican government awarded her Mexico’s Order of the Aztec Eagle Award, the highest decoration it awards to foreign nationals.

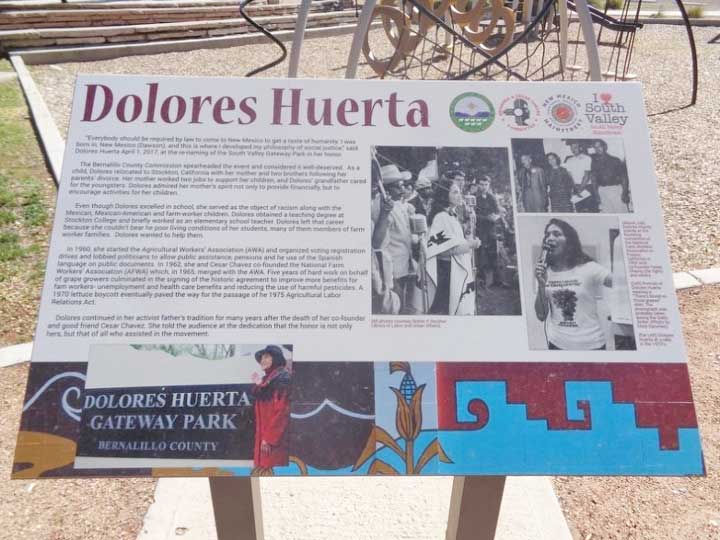

While Dolores Huerta has played a crucial part in many different communities across the U.S., from California to New York, I believe that New Mexico in particular has a special place in her heart. On April 1, 2017, the Gateway Park in Albuquerque’s South Valley was renamed in her honor. In an interview during its unveiling, Huerta confessed, “Everybody should be required by law to come to New Mexico to get a taste of humanity. I was born in New Mexico, and this is where I developed my philosophy of social justice.” As a California girl myself, her words ring true to my own experience as a UNM student. As an undergraduate, my courses in Spanish and Chicanx Studies revealed the incredible history and contributions of Latinx leaders in New Mexico and in the greater Southwest, a history that was never highlighted to me in high school. Now as a graduate student in the department of Spanish and Portuguese, I get to teach Spanish as a Heritage Language course to undergraduate students through a social justice lens that binds identity, community, family, and language all in one. As Huerta conveyed, New Mexico has a glow to it, and it builds with every person who is born or has migrated here.

Chicanx Studies professor at the University of New Mexico, Dra. Elizabeth Gonzalez Cardenas, is a native Californian herself who has also demonstrated the direct impacts that Huerta has had on her life. She recounted to me a tradition she helped start in 2005 when she was a student at Dominguez Hills Community College: “We decided to name the graduation The Dolores Huerta Graduation Celebration as a way to acknowledge the important contribution of Dolores Huerta, a Chicana/Mexican that was fierce and advocated for human rights. We rarely learned about women leaders who made history and were involved in making the world a better place, so as founders, we decided that the graduation had to be named after Dolores Huerta.” This year will mark the 18th Dolores Huerta Graduation Celebration.

Dolores Huerta will be 93 years old this year on April 10th, and while she continues her passion to fight for others, it will be the responsibility of those whose lives she has impacted to continue her work and to keep her fight alive long after she’s gone. Her leadership serves as an inspiration to all, but especially to Latina women out there who see her and believe that we can be leaders; that we can be heard; and that we can be damn unapologetic about it.

Sources

National Women’s History Museum: “Dolores Huerta Biography“

NPR: “Delores Huerta: The Civil Rights Icon Who Showed Farmworkers ‘Si Se Puede’“

Source NM: “Dolores Huerta comes home to New Mexico to Push for Build Back Better“

The Historical Marker Database: “Dolores Huerta“

Recuerda a César Chávez Committee: “Dolores Huerta“

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

NEW MEXICO’S AMAZING BLACK HISTORY

By Rob Martinez, State Historian of New Mexico.

“African history runs deep in New Mexico. Black history is often framed within the institution of slavery, but in New Mexico, New Mexicans of African descent were ambassadors, explorers, colonists, soldiers, cowboys, discoverers, settlers, businessmen, educators, and much more.”

SCANNING FOR STORIES

It was a Friday afternoon in November and I was driving on a state road through the hills of the Mimbres Valley. The entire landscape was bathed in a golden hue because the tree leaves had made their full conversion to a bright yellow color just before falling off the branches.

REFLECTIONS ON THE LOSS OF A NEW MEXICO CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER

By Carlyn N. Pinkins, M. A.

“The Dr. Harold Baileys of the world should inspire us all to do what we can to leave our communities, our towns and cities – our great state – better places than we found them. While we do our part to create the Dr. Harold Baileys of the future, we should also strive to make sure that the Dr. Harold Baileys of our past and present are never forgotten.”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

MARIA VIELMA

Maria Vielma is from San José, California and received her Bachelor’s in Criminology and Spanish from the University of New Mexico. She is now in the final stages of her Master’s degree in Hispanic Southwest Studies also from the University of New Mexico.