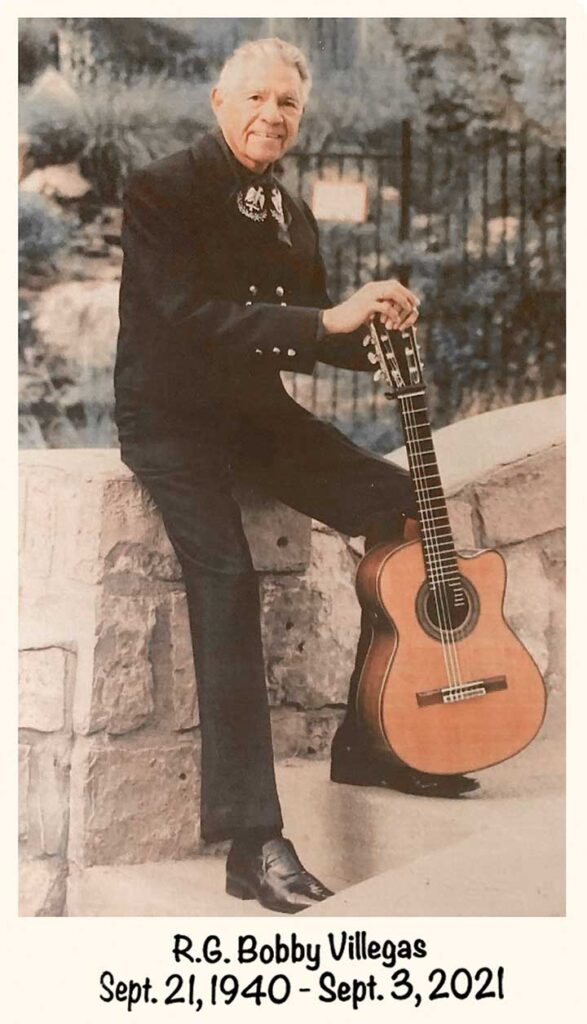

EL GRITO ETERNO: IMAGINING VICENTE FERNANDEZ AND REMEMBERING MY FATHER

The mariachi legend, Vicente Fernandez, passed away late last year at 81. Affectionately known by his legions of fans as ‘Chente,’ he left a legacy that will likely go unmatched.

PHOTO CAPTION: Vicente Fernandez in 1965. Photo from Wikimedia Commons.

SHARE:

The mariachi legend, Vicente Fernandez, passed away late last year at 81. Affectionately known by his legions of fans as “Chente,” he left a legacy that will likely go unmatched.

Chente was Mexico’s patron saint of gritos — mariachi howls that rattle to the core. His music provided the background for millions of lives, animating generations of quinceañeras, weddings, birthdays, and tequila-filled parties running late into the night. Mariachi standards like El Rey and Cucurrucucu, Paloma became his songs, even though he was not known to write any of his own music, according to the bio from his official website.

His trademark look was a charro (Mexican cowboy) outfit, complete with a giant sombrero hovering over a rugged, bigotes-covered visage. If you have ever seen the movie Coco, you have seen the spirit and image of Fernandez in the story’s antagonist, Ernesto de la Cruz. This epically narcissistic and charming character was based on Jorge Negrete, Fernandez’s mariachi predecessor and one of Mexico’s biggest stars during its golden age of cinema.

Vicente played himself in several movies and was already on the map as a veritable “Frank Sinatra of Mexico ” when he released his biggest hit, Volver, Volver, in the 1970s. Initially written by Fernando Maldonado just a few years earlier, Volver, Volver became a ranchera anthem, a yearnful classic of lost love, and a rallying cry for giving it another try.

If there is one quality that characterizes Chente and mariachi ethos, it is pride. Unfortunately, up until recently, that pride has been predominantly male. Fernandez’s overflowing bravado celebrates a distinctly Mexican pride while also providing a haven for the best and worst of machismo culture.

But that was the past. Even though there is no way around the patriarchal underpinning of many of our traditions, we can reinterpret and reinvent them. Along with Fernandez, powerful divas like Lola Beltran and Ana Gabriel gave voice to these traditions. Recently, all-female groups like Mariachi Divas and Flor de Toloache are putting on the traje.

So, remember the pride of Vicente “Chente” Fernandez and throw back a cold one as you let out a few soul-squeezing gritos. Because if there is anything Chente has taught us and generations to come, it’s how to howl.

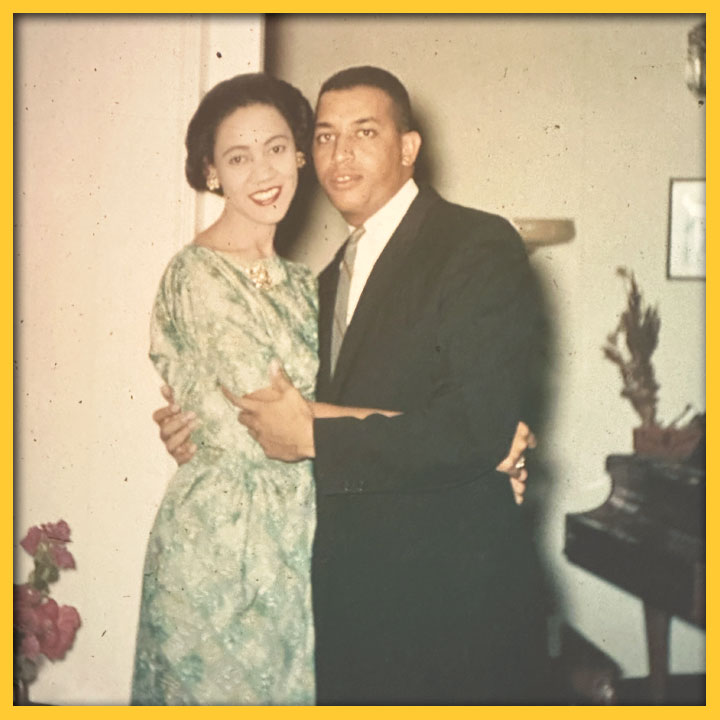

Remembering My Father

Nothing certifies me to write about mariachi with any authority. I am no musician. I’m not even from Mexico. I’m from a small town in southern New Mexico known for its crashing aliens. (Apparently, our future selves still drive terribly!)

However, I know a little about mariachi music because those tunes were some of the first sounds that my siblings and I heard growing up. Our father was a mariachi (charro outfit y todo!), a real crooner and requintista, or player of the requinto, a small guitar built for shredding.

My grandmother and grandfather were both musicians. My dad turned out to be a natural, first learning violin while growing up in Las Cruces, then playing lead guitar for a Chicano rock band, the Knightsmen. They played covers of all of the bangers of their day, from artists like Little Richard, Elvis, and Santo & Johnny. They would perform at dives in Las Cruces and small towns like Vado and La Mesa. As kids, he used to tell us stories about playing at strip clubs (nice strip clubs, expensive ones) in Texas in the 60s, where his band even backed Bo Diddly once.

As he reached middle age, he started to capitalize on mariachi chops, his inheritance. Unlike the operatic boom of Chente, my dad played trio music, a-la Los Tres Reyes and Los Tres Ases. He always played with a partner, usually a chord-strumming baritone who could carry the tune while my dad’s long, skinny, Hendrix-like fingers utterly slayed leads.

They played Chente-style rancheras, but they specialized in boleros, or ballads, like Reloj, Cuando Calienta El Sol, and Sabor a Mi. He often played at gatherings for family and friends, so I saw him perform a lot, especially as a little kid. I remember his larger-than-life personality, his jovialness, and his patience as he let me run up to him in between songs and reach for a strum or examine the metal horseshoe embellishments that lined his traje.

My father passed away in September, just days before his 81st birthday and months before Chente‘s passing. Like Chente, my dad was a child of 1940 (“too young for World War II, too old for Vietnam,” he used to say, regarding the draft). Also, like Chente and so many others, my dad’s music often drew from the experience of grinding struggle that comes from rural poverty, and at a time when the country seemed to be thriving with abundance.

Though my dad was a guitarist, he sang a lot, and you could hear the ambition in his voice. Mariachi music helped him and so many others to soar powerfully, however briefly.

RIP to the generation that taught us to howl. May your gritos live on!

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

REFLECTIONS ON THE LOSS OF A NEW MEXICO CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER

By Carlyn N. Pinkins, M. A.

“The Dr. Harold Baileys of the world should inspire us all to do what we can to leave our communities, our towns and cities – our great state – better places than we found them. While we do our part to create the Dr. Harold Baileys of the future, we should also strive to make sure that the Dr. Harold Baileys of our past and present are never forgotten.”

RUDOLFO ANAYA: CATCHING CULTURES IN BLESS ME, ULTIMA

By Richard Wayne Etulain

Anaya greatly expands the cultural contributions of his novel by combining the usual (Bildungsroman—growing up theme) with the unusual (complex, diverse New Mexico Hispanic culture)…

UP BY OUR BOOTSTRAPS; TWO LIVES IN RETROSPECT

By Finnie Coleman

I found myself fascinated with Dr. McIver’s transition from the stultifying hopelessness of the Segregation Era to the wistful hopefulness of the Civil Rights Era…

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

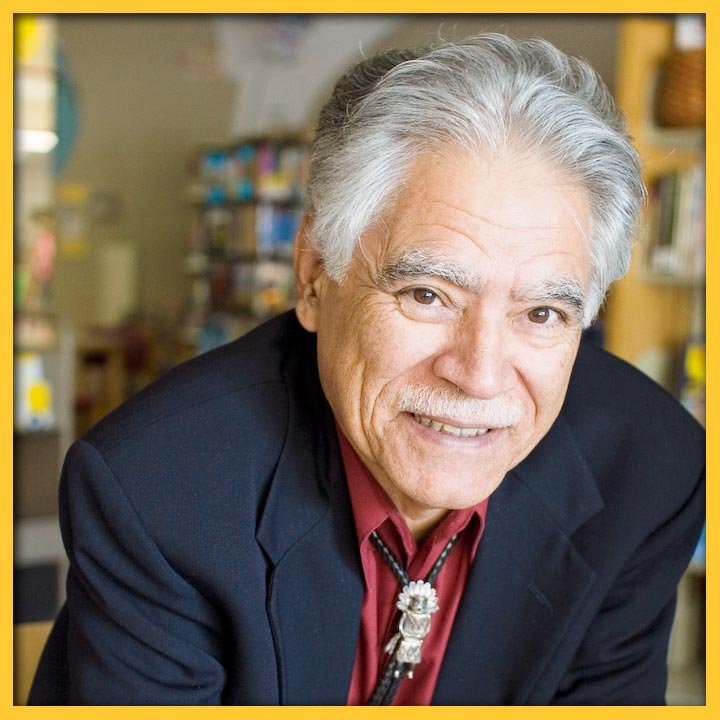

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

MATT VILLEGAS

Matt Villegas is a massage therapist, educator and writer living in Albuquerque. He was born and raised in Roswell.