FISH NOT FLESH: SYMBOLISM OF THE NEW MEXICO LENTEN FEAST

Ultimately, it is the return to life after the darkness of death that is at the heart of Lent and Easter Sunday, and it is this contrast that is represented in the food eaten by New Mexico Catholics.

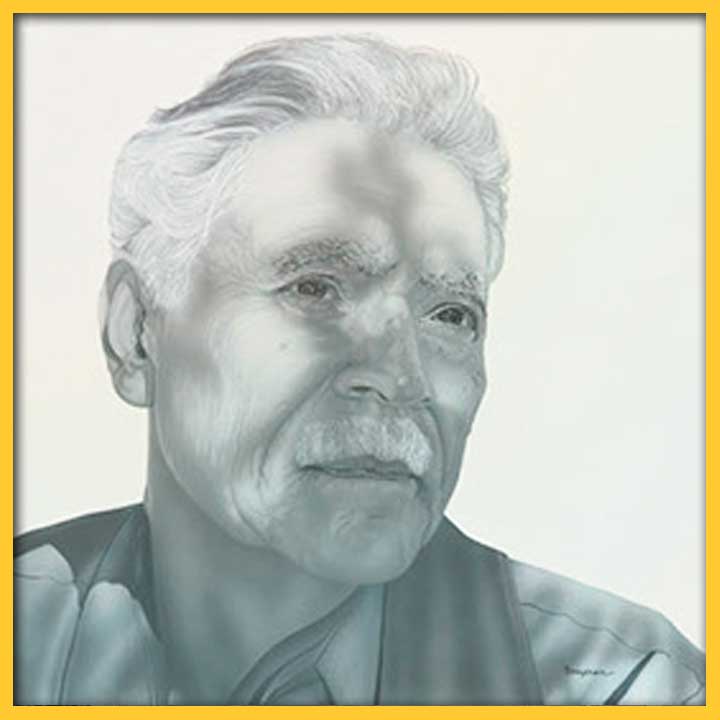

PHOTO CAPTION: Vanessa Baca.

SHARE:

When I was growing up, my New Mexico Catholic family each year would enjoy what we call the Lenten meal. Though Catholics are asked to eschew eating meat on Fridays during Lent, it was the Good Friday meal that held a special place in my family’s heart. On Good Friday in the Land of Enchantment, Catholic families gather together to observe the mystery of the death of Jesus Christ by eating a uniquely New Mexican meal made up of foods with significant meaning. Our culture is not unique in how we honor this religious day – by the sharing of specific foods with family and friends to mark the importance of the holiday. However, here in New Mexico, the Lenten meal has a meaning and identity all its own.

When I was a little girl, my grandmother, whom we lovingly called Nana Jean, spent the whole week preparing the Lenten meal She would put a Crock-Pot of beans to cook “low and slow,” as she would say. She separated the canned salmon from its skin in readiness to form the salmon patties that were the main course. She separated the egg yolks from the whites as part of her method of making torta de huevo, a wonderful dish of shallow-fried egg white patties. She rinsed and cleaned a large bowlful of spinach for quelites, a wilted green cooked with garlic and sprinkled with red chile seeds and served with beans. Speaking of red chile, part of the process involved her soaking, cooking and mixing up the red chile pods to make the red chile sauce that would blanket the tortas. She would start her dough for her homemade tortillas, with which we would sop up all that delectable red chile. My favorite part of her preparations was when she began separating egg whites and yolks to start making her delicious natillas, a vanilla custard sprinkled with cinnamon and are traditionally eaten during Lent and Easter. The memory of this meal remains in my heart as one of my favorite family gatherings.

Last year, I was invited to a Jewish friend’s home for the Passover Seder meal and was struck by similarities between some of the Seder foods set out for family and guests, and the delicious comida that my own family eats every Good Friday. Rachel, who was from a family of Sephardic Jews, explained the meaning behind the Passover Seder and its connection to her family’s Jewish faith. Passover is the celebration of the exodus of the Jewish people from their slavery in Egypt, and is observed in a specific way with foods that have significant symbolism.

The Passover Seder includes a dish of hard-boiled or roasted eggs, usually charred. The charring is symbolic of the sacrificial animals offered on Passover. Eggs themselves are symbolic of life, death and rebirth, which is a powerful facet of both Passover and Easter since both holidays represent the reversal of death and the reclaiming of life. The Seder dinner also includes what she called karpas, bitter greens dipped in vinegar or salt water to symbolize the bitterness of slavery and the tears shed by the many Jewish slaves. Similar to the quelites we eat on Good Friday, the greens also signify the flourishing of vegetation in the springtime and a connection to the earth.

Matzo, an unleavened flatbread, is usually part of a Seder table as well. Being unleavened means it does not have yeast as most bread does, and as such, does not rise. The traditional story about matzo is when the Jewish people were granted their freedom from the Pharaoh, they had to leave Egypt quickly in fear that Pharaoh would change his mind, so quickly that their bread had no time to rise. Similarly, the tortilla that is always eaten with the New Mexico Lenten meal has no yeast and is unleavened bread.

A significant difference between the two meals is in the consumption of meat and fish. Lamb, specifically lamb shank or a lamb shank bone, is traditionally part of a Passover Seder. For Catholics, lamb might be eaten on Easter Sunday but not as part of a Good Friday meal. Catholics have historically avoided eating of meat on certain days during Lent, including Good Friday. The Catholic Church’s Lenten traditions, including culinary, were established in 325 at the Council of Nicea, when fasting and abstaining from eating meat were emphasized. The Bible itself neither mandates fasting nor requires avoiding meat on Fridays. As well, in medieval times, the Catholic Church encouraged consumption of fish in order to boost that particular industry. Fish was more widely available to poorer families than meat, and as well, the inherent connection of fish to early Christianity was emphasized as another reason to consume fish over meat on holy days. Eating salmon patties as part of the Lenten meal is our way of honoring that connection.

The inclusion of sweet dishes is part of both the Passover Seder and the Good Friday Lenten meal. The Seder always includes a dish called haroset, which is a mixture of chopped apples or other fruit, nuts and honey, which symbolizes the mortar used by the Jewish slaves to build the Pharaoh’s monuments. Catholics include natillas, also egg-based, tying in the connection of eggs and their symbolism to the circle of life. Having something sweet to finish the Lenten meal reminds us of the sweetness of life, even in the midst of darkness.

Ultimately, it is the return to life after the darkness of death that is at the heart of Lent and Easter Sunday, and it is this contrast that is represented in the food eaten by New Mexico Catholics. There is the heat and spice of red chile, the soothing and life-affirming taste of eggs, the salty tang of the salmon, earthiness of the beans, vibrancy of the quelites, and sweetness of the natillas. This combination of foods is a central part of the culture of New Mexican Catholics, and in addition to having symbolic meaning and religious connection, it also represents the coming-together of family and the sharing of history, faith, love, and tradition.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

CULTURE ALSO COMES IN THROUGH THE KITCHEN

By Teresa Dovalpage

“Here in Hobbs, where I currently live, the Cuban community, very small when we moved here seven years ago, is growing fast.”

RUDOLFO ANAYA’S MAGIC WITH WORDS

By Chris Chaves

“It seems that, for Anaya at least, libraries and the magical words hidden in their books can serve to impart knowledge, facilitate love, and encourage empathy about others.”

ECOLINGUISTICS AND HOW LANGUAGE CAN SAVE THE WORLD

By Monika Dziamka

“It’s hard to talk about gender, equality, and equity without also talking about issues surrounding sustainability and the environment—which in turn relate to issues of power, colonialism, and capitalism.”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

VANESSA BACA

Vanessa Baca is a cook, writer, public relations professional, blogger and podcaster. Her food blog: www.foodinbooks.com, reviews various works of literature and recreates the food references in these books. Her podcast: www.anchor.fm./cookingthebooks, showcases literary cuisine with a variety of guests. She is a native New Mexican, lived briefly in Spain, travels extensively, and has taken cooking lessons in several countries.