SHARE:

Each year grullas arrive by the hundreds, settling over the valley’s farm-fields, seeking shelter on vegetated islands of the Rio Grande. But the year my boy was born, I missed their lone, throaty-calls, sitting instead within dark rooms, trying to bond with this new life brought into the world.

Santiago was born on a Friday; after 17 hours they had to cut him out of me, my petite frame too small for his entrance into this world.

Migration into motherhood was not an easy one.

The year my boy was born I was not witness to the grullas autumn arrival, instead, I was confined indoors, and my newborn and I fought with one another. He cried for milk. I lacked sleep. He struggled to gain weight. I struggled to hum a song soft enough to soothe him. Autumn waned, shadows of the grullas appeared through my window as they fed in the terrenos nearby.

The grullas did not notice my slip into depression. Migration into motherhood was not an easy one.

Cranes are of the family Gruidae, long-legged, long-necked birds, consistent and familiar visitors to this valle, wintering in my father’s fields since I was a child.

Sandhill crane; Antigone canadensis. But in my family’s native language, these birds are only known by only the word-name — grullas.

The season and year I migrated from “biologist” to “mother”, the grullas arrived as always, but my relationship to this place, this valley landscape, had changed. My boy and I struggled to know one another.

November, two months after the birth, I drove down Highway 47. Grey-coated grullas foraged in the fields alongside the highway, the patchwork fields in and along the communities of Tomé and Adelino providing grounds for these wintering birds. Pulling over on the highway’s shoulder, I sat watching thru the windows the gathering of birds, asking myself, will I ever reach a place of acceptance? I sat in the car, the baby asleep in the car seat behind me, and just watched the birds in the fields, a deep depression and resentment already settled into my bones, as ancient as these birds themselves.

“The Sandhill crane is believed to be one of oldest living bird species in the world, having occupied our planet for roughly two million years. Throughout their existence, Sandhill cranes (Antigone canadensis) have been migrating thousands of miles between their summer and winter ranges.” New Mexico Wildlife Federation

I search for describing how and why these birds became, and remain, so important to me.

I’d been introduced to grullas as a young girl; they were the birds occupying Papa’s dormant alfalfa fields in fall and winter. These birds always marked season and time. “Ya se van las grullas,” Papa would say, knowing he could soon start planting. Or “ya llegaron las grullas,” meaning winter was almost truly here. And so began the essence of grullas grounding me in specific time, season, and place.

*

Las grullas journey across the skies of this valley every morning and every evening, like clockwork, like all that is brilliantly familiar during these cold winter months. Two of my friends are now “expecting” their “first” in the next two months, and I think of them, maybe eager and anxious, but both of them unprepared for what is to come. The pain of childbirth, the soon-to-be lack of sleep, the high-pitched cry of a newborn and diapers to change. Is either of them really ready? And my own 5-year-old boy now fills the house with constant requests and laughter, both of which I can no longer do without, but only after a very long period of adjustment. And while the debates in our immediate world rage on, the fact remains: We are bound by the individual ordinaries of our everyday lives, the momentary intricacies, the minor nuances between days and weeks. Seasons change, months pass, the grullas will eventually migrate out of this valley again, as they’ve always done for generations each spring. But for now they are here, grounding us in season, in time, in place, making their entire appearance as a smoke-colored mass flying across the sky. Grey, nearly unseen against a winter sky, so often times heard before they are seen.

They are not metaphor, they are not symbol nor talisman. They are grullas, an ancient and living species, returning again and again each autumn, a constant, a reminder, an unabashed and perpetual returning. They are migratory birds.

What I’ve discovered, with brutal honesty is that in very subtle, almost unknowable ways, these birds claim me. Their presence, their arrival in autumn, their long deep-winter residency, and then their just-right-spring-departure, they claim me in every sense of the word.

The way my body stills when they fly over-head. The subtle calmness that comes over the afternoon when grullas fly from the fields back into the bosque.

These birds lead me out of lonely, if only just for a moment, as I watch a group of them fly across a darkening-winter-evening. Seeing them distills the worry of my day. They open in me an opportunity to question – what loveliness did I witness or add to this ordinary day? They urge me to meditation, however short or long-lived, and it is their soft grey existence in the sky that makes me stop for a moment, drift into a thought towards the Divine, the power that carries me into a horizon of a softer honesty.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

SPACESHIPS, RAY GUNS, AND LIFE LESSONS

By Melinda Snodgrass

“science fiction allows you to discuss difficult and fraught topics in what is a safe space and at arm’s length.”

LITERATURE AS GUIDEPOSTS ON MY IMMIGRANT JOURNEY

By Kei Tsuzuki

“What I have learned from books is that there is no one story that explains the world to us or captures our identity entirely. There is power in the specificity of each of our stories…”

A DIFFERENCE-MAKING BOOK

By Richard Etulain

“Many authors hope their histories, novels or other writings will make a difference — that their works will catch readers’ attention and influence their thinking and actions.”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

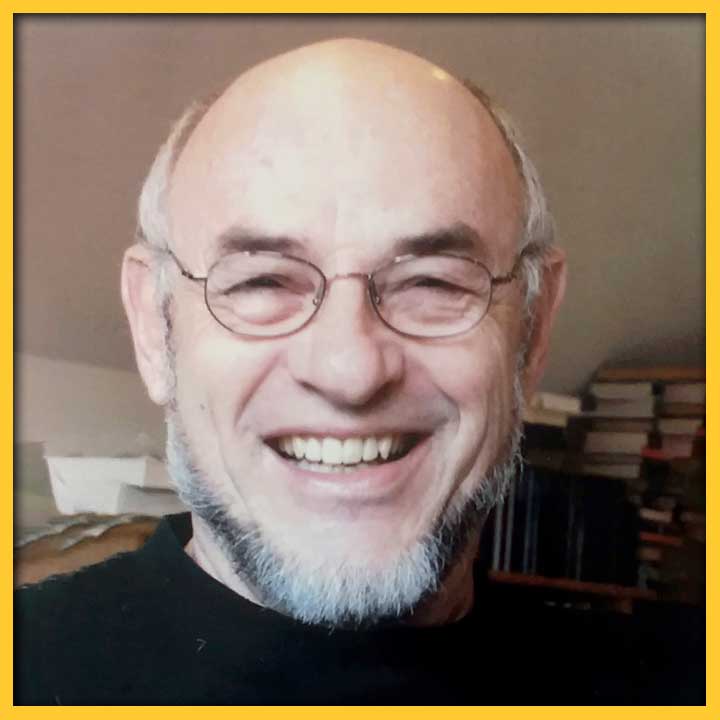

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

LEEANNA TERESA MARTINEZ Y TORRES

L.T. Torres is a native daughter of the American Southwest, with deep Indo-Hispanic roots in New Mexico. She has worked as an environmental professional throughout the West since 2001. Her creative non-fiction work has been published in Blue Mesa Review, Tupelo Quarterly, and is forthcoming in an anthology by Torrey House Press (2021).