SHARE:

Once, as an undergrad at the University of New Mexico, I was crossing the street at Yale and Central. A professorial-looking white man approached the crosswalk shortly after me, both of us now waiting for the light to turn green. He asked, “Did you just get here?” “Yeah, just now,” I replied, thinking here meant the crosswalk. “Well, welcome! Welcome to Albuquerque, welcome to New Mexico, and welcome to the U S of A!” he said with genuine excitement. Too embarrassed to correct him, I muttered a “thank you.” The light changed to green but I didn’t cross.

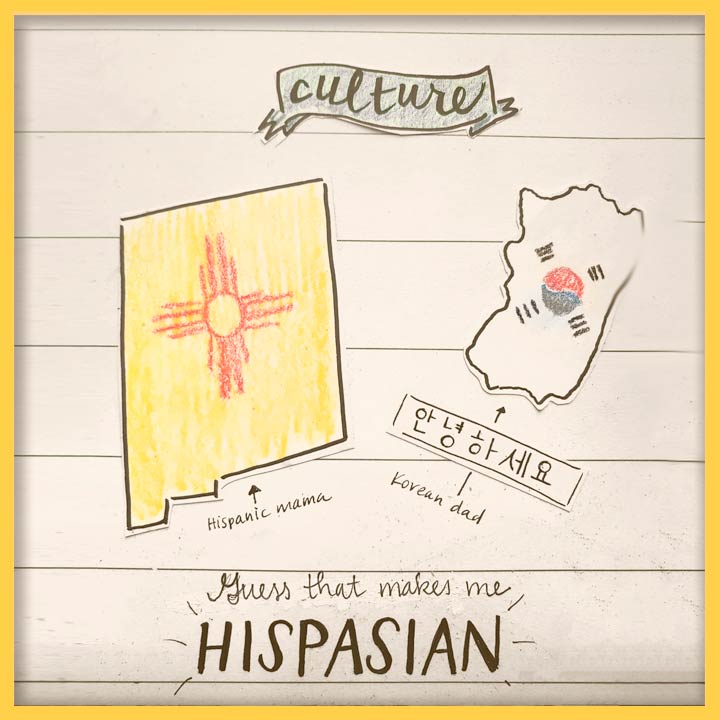

The questions are always the same: “Where are you from?” or worse, “Where are you really from?” or worse yet, “What are you?” To the last, when I was little, I would say, “I’m half Korean, half my mommy.” That’s when my mom coined a term I could answer with: I’m Hispasian. To us, Hispasian describes our family’s mix of race (the way we look), ethnicity (the culture we practice in our daily lives), nationality (the country we hold citizenship), and heritage (the identities of our ancestors).

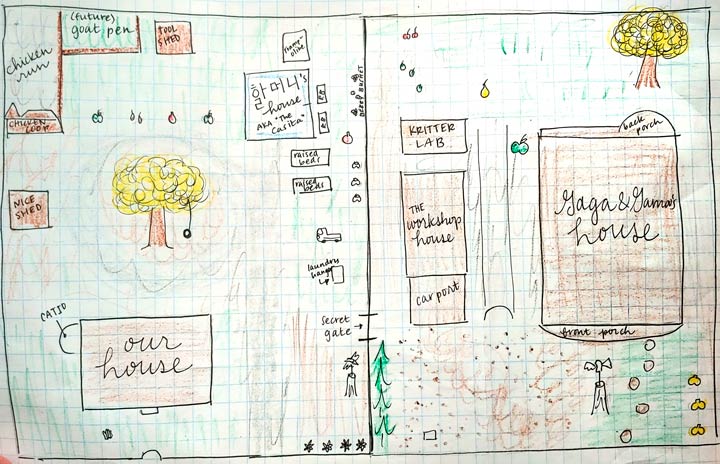

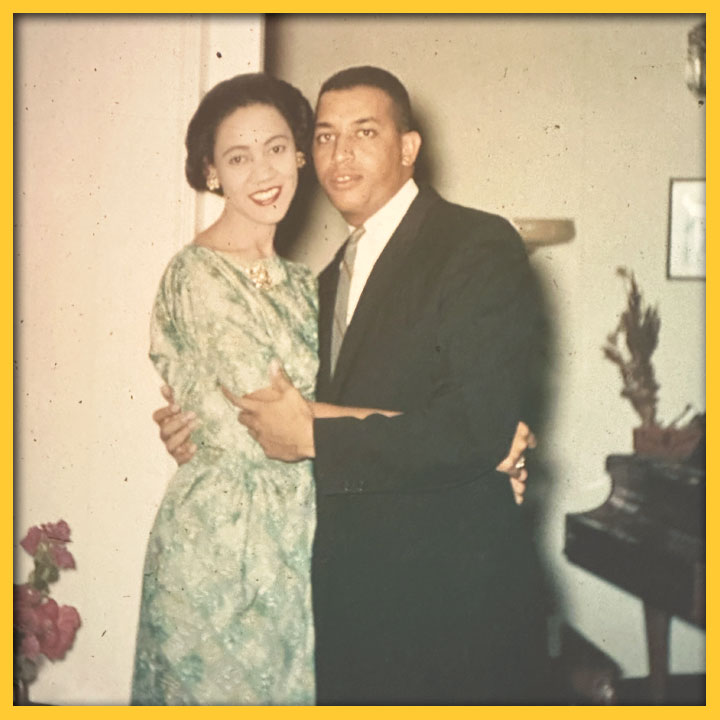

Where am I really from? At that crosswalk, I could have told the man that I am from the (mostly white) Taylor Ranch suburbs of Albuquerque. That’s where I grew up. Or I could say my dad was born in South Korea and raised in Cherokee, Iowa (even more white than the Taylor Ranch suburbs). Or I could say that, on my mom’s side, my grandpa calls my grandma a “city girl,” because she grew up on Seventh Street and Mountain Road while he was raised on Lovato off Isleta, or that they raised my mom in Wells Park. Or I could say I’m from Atrisco and 47th, one block west from El Super supermercado, where I live now in the house next door to my maternal grandparents.

But when people ask me, “Where are you from?” they are not asking for that specific geography. No one is satisfied when I say “here.” Where are you from? is a euphemism in this so-called “post-racial” world for what race are you? So inextricably tied are place and identity, so conflated are race, ethnicity, and nationality, that an Asian-looking woman often cannot fit into peoples’ predefined image of a Nuevomexicana.

I attended UNM on a National Hispanic Merit Scholarship. I’ve had to justify, to myself and others, receiving money meant for a group that I do not physically represent. It was not intentional, my receipt of the scholarship. When you take the PSAT, you to fill in the bubbles: this one for Asian, this one for “non-white Hispanic.” At 17, I didn’t think twice about who I was. I knew I saw my dad’s eyes and nose when I looked in the mirror. That’s my Asian race. And I knew that for dinner my mom, maiden name Ronquillo, was making enchiladas again, and that we’d sing cordero de Dios in mass on Sunday, and my dad, enamored with my mom and her culture, was stringing red chile ristras in the garage. That’s my Hispanic ethnicity. And by marking “non-white Hispanic,” and getting a good score, I received the money. Sometimes I still feel sorry—did I take it from someone “more Hispanic” than me?—but I used my time at UNM to learn about identity construction.

It was in a freshman Intro to Sociology class that I learned the difference between the terms race, ethnicity, nationality, and heritage. As someone who gets questioned so frequently on those topics, the difference is important to me. But it’s a miracle I learned anything in that class because I was constantly distracted by the white man who would become my husband. Marrying a white man, growing up in a suburb, my dad’s all-American-but-the-only-Korean-in-town upbringing in Iowa—this part of my history requires me to examine the role whiteness plays in my life, which I view as my connection to my American nationality. Americanization and whiteness have shaped my family’s history and language for generations past, present, and future.

When it was time to bear the next generation, my husband and I gave our son the most Hispasian American name we could think of: Joaquin Auh Krukar. With a name like that, my son represents his own tricultural blend, one that defies the tricultural myth of New Mexico. His surname, and his inexplicably blond hair and blue-green eyes, represent his dad’s race and heritage (American Anglo with ancestral ties to Croatia). From me he gets his kiss-at-the-corner eye shape, and his middle name, which is my maiden name (pronounced “oh”, translated from Korean to English by way of French, by my dad’s dad when he brought my dad to the United States from South Korea by way of Kamala, Uganda). And Joaquin, for San Joaquin, the patron saint of grandfathers, whose feast day my Joaquin was born near, and inspired by Yo Soy Joaquin, a poem I first read when, in my last semester of undergrad, I finally mustered the courage to take a Chicano/a/x studies course.

How I admired the profesora, and how I envied so many of the other students, who looked like her, like my many maternal cousins, like how I look in my mind’s eye. And how uncertain I was—despite knowing my great-grandma’s recipe for torta de huevo by heart after making it with my grandma every Good Friday, despite my grandpa’s voice in my ear, hola mija—in my own latinidad that I kept secret until the end of the semester. Without a race or face that fits into the tricultural myth of New Mexico, I am in a constant state of contradiction; I am always at the crosswalk. What can I do besides borrow words from the poet of Yo Soy Joaquin, Corky Gonzales:

La raza! / Nuevomexicana! / Korean! / ?? ??! / Hispasian! / Or whatever I call myself, / I look the same / I feel the same / I cry / And / Sing the same.

This column was funded in part by a generous grant from the McCune Foundation.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

REFLECTIONS ON THE LOSS OF A NEW MEXICO CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER

By Carlyn N. Pinkins, M. A.

“The Dr. Harold Baileys of the world should inspire us all to do what we can to leave our communities, our towns and cities – our great state – better places than we found them. While we do our part to create the Dr. Harold Baileys of the future, we should also strive to make sure that the Dr. Harold Baileys of our past and present are never forgotten.”

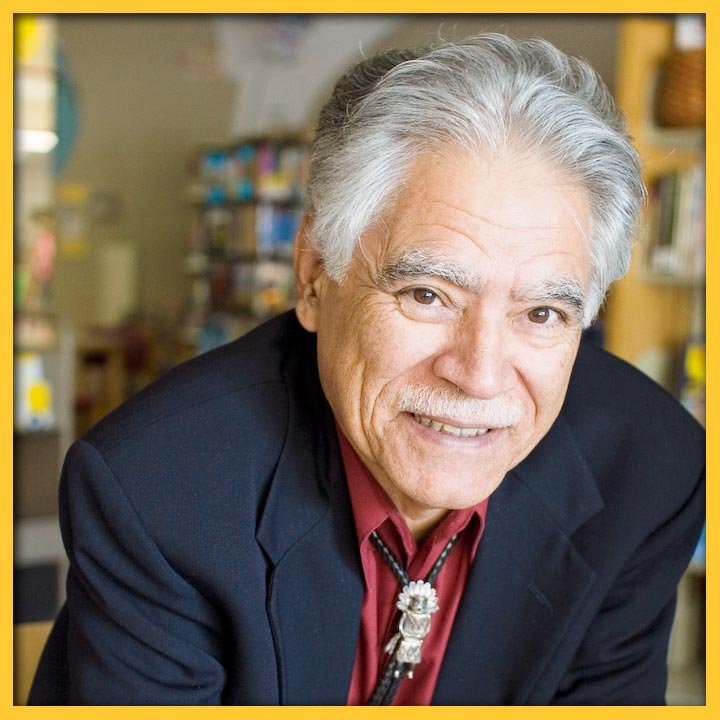

RUDOLFO ANAYA: CATCHING CULTURES IN BLESS ME, ULTIMA

By Richard Wayne Etulain

Anaya greatly expands the cultural contributions of his novel by combining the usual (Bildungsroman—growing up theme) with the unusual (complex, diverse New Mexico Hispanic culture)…

UP BY OUR BOOTSTRAPS; TWO LIVES IN RETROSPECT

By Finnie Coleman

I found myself fascinated with Dr. McIver’s transition from the stultifying hopelessness of the Segregation Era to the wistful hopefulness of the Civil Rights Era…

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

MELISSA AUH KRUKAR

Melissa Auh Krukar's last name is pronounced "oh crew-car." She is a Hispasian homemaker in Albuquerque, NM, where she lives with her husband, son, cats, chickens, and sheep.