SHARE:

I have been an immigrant twice in my life—first when my family moved from Japan to Quebec when I was 2, and again when I followed love to New Mexico at 26. From a quiet Asian girl without a fluid grasp of language—Japanese, English or French—to an immigrant advocate today hoping to help refugees find their own voices in America, my journey has been full. And through it all, understanding my immigrant story has been made immeasurably more clear through literature.

Books have been profound guideposts on my life’s journey. Not only have they provided direction and insight, they have signaled vantage points to the larger landscape of humanity— “Stop here for a great view.” Indeed, they have helped me understand, discover and rediscover the beauty and complexity of the human landscape.

The first of such books to guide me, as I stood on the cusp of adulthood, was Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye. I often say that reading The Bluest Eye in college changed the trajectory of my life. Her writing, revelatory in its beauty and lyricism, cracked open a deeper understanding of race and gender that I had not encountered before. Never letting us forget the context of White racism, the story nonetheless is not White-centered; she gives voice to the full complex humanity of her Black characters, exploring topics such as colorism, classism, sexism and internalized racism. While doing so, she does not flinch in asking us to consider our own culpability in the acts of violence we permit in community.

I was hooked. As my nascent Asian American identity was coming into focus, I knew literature would help me better understand the world around me and my place in it; it would inform how I could talk about racism in America as well as the internal conflicts within our Asian communities; it would teach me about specificity in oppressions while also showing common bonds between the oppressed; and, at its best, it would bring me closer to understanding the transcendent beauty of life as all great works of art do.

So, rather than major in the sciences despite studying pre-med, I joined the English department and wrote my senior thesis on Maxine Hong Kingston’s novels Woman Warrior and China Men. These books served as guiding tomes to a generation of Asian American readers at a time when few books by Asian American writers were being published. Kingston still needed to educate a larger audience about this country’s exclusionary history against the Chinese, but it is her exploration of modern Chinese immigrant life that resonated the most. Her portrayal of family life steeped with modern silence and generational longing felt keenly intimate and familiar. What grievances are brought with us across oceans, what stories do we forget or rather choose not to tell? She asserts that we cannot be afraid to ask.

Li-Young Li’s slim book of poetry, Rose, published just before I graduated, promised a new perspective. His poem “The Gift” still stands as one of the most tender portrayals of manhood I know. Filled with gratitude for his Chinese father despite his father’s disciplinarian ways, Li beautifully balances the hardship of history with the possibilities opened by love. To see this in Asian American writing was new for me. Years later, Chang-Rae Li would echo a similar sentiment in A Gesture Life and more recently in My Year Abroad. Though the books are widely different in narrative, both explore the possibility of change for Asian men living in America, ushered by a deeper understanding of love.

I realize that over the years, this understanding of love has been a theme that I have been drawn to in books over and over again. That love I followed to New Mexico all those years ago? — you can blame it on literature. I was astounded to find anyone who had read Jeanette Winterson at the time, a new lesbian British writer, let alone to find them in the desert of New Mexico. Late into the night, we pondered questions of love, understanding, acceptance and happiness explored in Winterson’s Sexing the Cherry and The Passion, and still reminisce about their meaning after 29 years of marriage!

As a mother, I am excited to have a daughter who is studying English in college now. On a recent vacation, as we were parting ways for new adventures, I handed her my copy of Nicole Krauss’s The History of Love. I had just reread it for the third time—not only to remind myself of the beauty of Krauss’s writing, but also to learn deeper about the effects of the Jewish diaspora and the role love plays in generational connections. The ending haunts me still. As she was finishing the book, my daughter texted in tears.

In my work at Kei & Molly Textiles, where our goal is to create meaningful jobs for recent immigrants and refugees, I see love at the center of all we do. As I carve out reading time in my current crazy work life, I find myself drawn to books that illuminate love as part of our human journey across cultures. Fatima Farheen Mirza’s A Place for Us beautifully captures contemporary American Muslim life and conflict between generations, often fueled by love but steeped in fear for parents and obligations for kids. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah centers a childhood love in its narrative, while teasing out differences between African and Black American culture that confuse love, sex, and identity; Ruth Ozeki’s A Tale For the Time Being tackles bi-cultural and bi-continental storylines that expose a modern Japan that struggles to embrace a love for living.

The list goes on.

What I have learned from books is that there is no one story that explains the world to us or captures our identity entirely. There is power in the specificity of each of our stories, to be sure, but we are always changing. And, in the end, in feeling where one journey overlaps another, we move closer to understanding how we are all connected in our humanity. Let’s stand at these vantage points together, and marvel at the landscape.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

NEW MEXICO’S AMAZING BLACK HISTORY

By Rob Martinez, State Historian of New Mexico.

“African history runs deep in New Mexico. Black history is often framed within the institution of slavery, but in New Mexico, New Mexicans of African descent were ambassadors, explorers, colonists, soldiers, cowboys, discoverers, settlers, businessmen, educators, and much more.”

SCANNING FOR STORIES

It was a Friday afternoon in November and I was driving on a state road through the hills of the Mimbres Valley. The entire landscape was bathed in a golden hue because the tree leaves had made their full conversion to a bright yellow color just before falling off the branches.

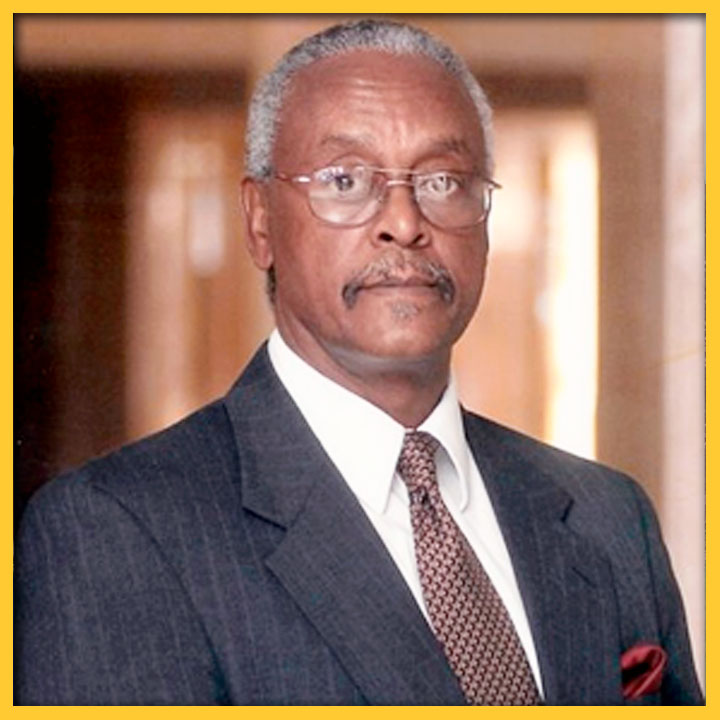

REFLECTIONS ON THE LOSS OF A NEW MEXICO CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER

By Carlyn N. Pinkins, M. A.

“The Dr. Harold Baileys of the world should inspire us all to do what we can to leave our communities, our towns and cities – our great state – better places than we found them. While we do our part to create the Dr. Harold Baileys of the future, we should also strive to make sure that the Dr. Harold Baileys of our past and present are never forgotten.”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

KEI TSUZUKI

Kei Tsuzuki is a social entrepreneur using creativity and commerce to change lives in Albuquerque. As co-founder of Kei & Molly Textiles, she demonstrates how an art studio can create good jobs supporting humane policies that help stabilize the lives of recent immigrants and refugees. Passionate about women's economic development, she helped launch Canada's first micro-loan funds and worked with New Mexico's ground-breaking social enterprise, Southwest Creations Collaborative, before starting Kei & Molly Textiles. When she's not tinkering with capitalism, she loves learning Italian, cooking with her kids, and, of course, reading great literature.