MAPPING QUEER HISTORY IN NEW MEXICO

Did New Mexico – or at least Albuquerque and Santa Fe– support a culture where queer people could be authentic and accepted, and nurture queer culture?

PHOTO CAPTION: The La Fonda Hotel in Santa Fe, New Mexico, ca. 1930-1940. Credit: UNM Library, William A. Keleher Collection.

SHARE:

For this month’s Augmented Humanity podcast, we’re talking with Dr. Amanda Regan, and Dr. Eric Gonzaba, co-creators of Mapping the Gay Guides, which is built around interactive geographic visualizations of the Bob Damron’s Address Books, a detailed travel guide for American gays, published 1964-2000. Preparing for the podcast, I naturally enough looked at New Mexico on the maps.

Starting with the first issue, six locations across the state are identified as being gay destinations, including the “very popular” News Room and Office bars in Albuquerque, and the Pink Adobe in Santa Fe, which is identified as being inclusive for lesbians (“girls”). Jacque’s in Roswell, like many of the places identified in the guide, are listed as “Mixed,” meaning “some straights” also frequent the locale.

As you click through the years, the number of gay-friendly locations increases but the picture remains remarkably stable, a scattering of hotels, restaurants, and bars where gay people felt welcome and safe. Some sound like dives, like Albuquerque’s News Room, which is annotated, “side entrance downstairs” but others were and are some of the nicest places around, like the La Fonda Hotel Bar in Santa Fe. On the flip side, the News Room had dancing.

Contrast the picture with other places in America, where gay gathering places were annotated with “Inquire Locally,” “At Your Own Risk,” “Dangerous- Usually Fuzz,” or “Raunchy/Hustlers”. The author of the Damron’s guides was well aware that the reaction to gay people ranged from tolerance to criminalization to lynching, depending on where in America you traveled. Although the 70s see a rise in “cruisy” areas (including the UNM Administration building!), New Mexico never sees the emergence of the private, dangerous or predatory places seen elsewhere.

Did New Mexico – or at least Albuquerque and Santa Fe– support a culture where queer people could be authentic and accepted, and nurture queer culture? Compared to neighboring states, New Mexico had far fewer gay destinations than Arizona or even Utah. However, as scholars have pointed out, queer histories and landscapes in New Mexico look very different from the male, Anglo-centric view presented by Bob Damron. Referring to women like Mary Wheelwright, who was able to live her queer identity, writer Alicia Ines Guzmán noted, “When white women from the East Coast came here, what they could do was different from what anyone else could do because of their privilege….For Hispanic people, the ability to live a specific way outside of the social norm could be more limited than the ability of anyone else who comes here.”

Spaces New Mexicans know and occupy are also vastly different than the urban-oriented Damron could have tracked. Photographer and Diné Pride activist Raphael Begay commented, “For so many who live in the rural Southwest, there is but a gas station and the landscape, with limited to no resources for queer individuals and communities. And so, how does one feel, embody, or express their queerness?” Perhaps this contributed to the phenomenon evident in the map, as queer spaces increase in Albuquerque and Santa Fe over time, while disappearing in other parts of the state.

Whether the Damron’s guides truly capture the full picture of historical queer spaces in New Mexico, it certainly adds another dimension to the evolving discussion. Tune in to Augmented Humanity, with new episodes every week, for a fuller discussion of the Mapping the Gay Guides project.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

REFLECTIONS ON THE LOSS OF A NEW MEXICO CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER

By Carlyn N. Pinkins, M. A.

“The Dr. Harold Baileys of the world should inspire us all to do what we can to leave our communities, our towns and cities – our great state – better places than we found them. While we do our part to create the Dr. Harold Baileys of the future, we should also strive to make sure that the Dr. Harold Baileys of our past and present are never forgotten.”

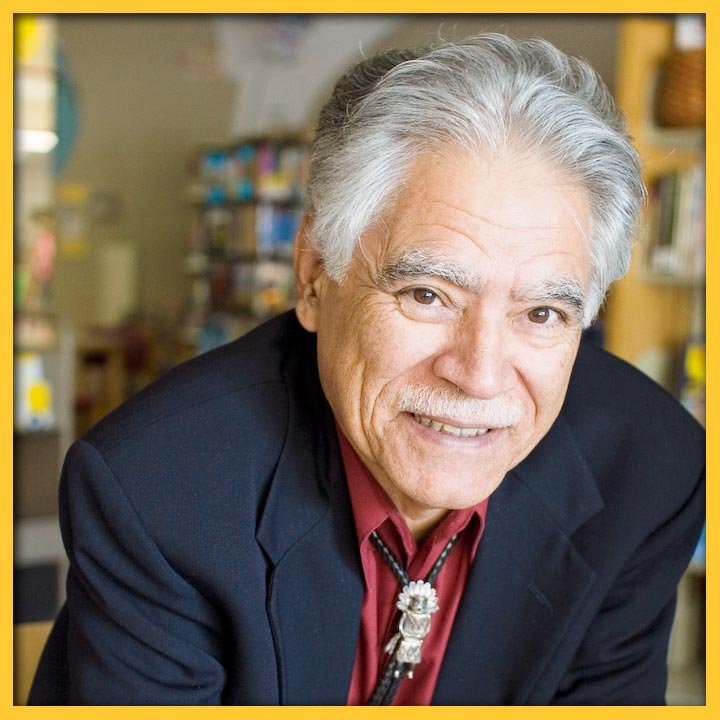

RUDOLFO ANAYA: CATCHING CULTURES IN BLESS ME, ULTIMA

By Richard Wayne Etulain

Anaya greatly expands the cultural contributions of his novel by combining the usual (Bildungsroman—growing up theme) with the unusual (complex, diverse New Mexico Hispanic culture)…

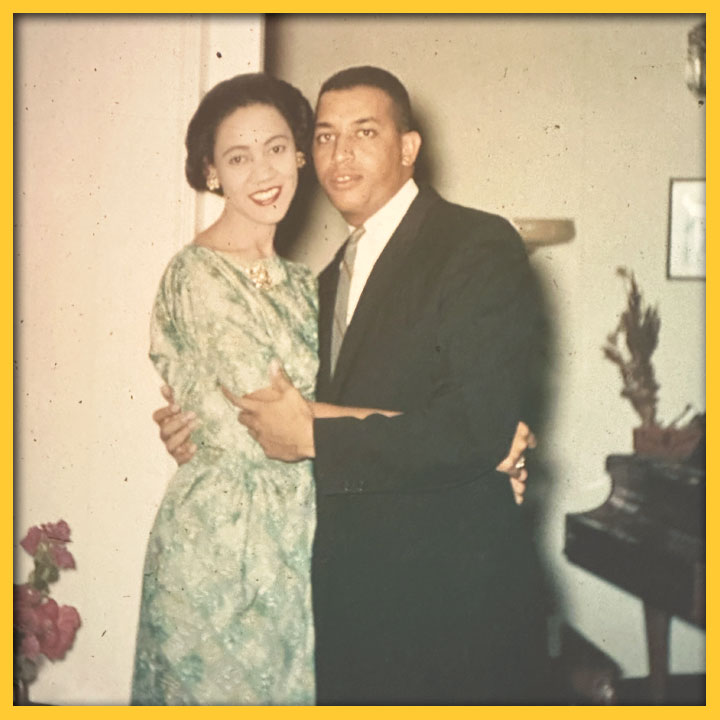

UP BY OUR BOOTSTRAPS; TWO LIVES IN RETROSPECT

By Finnie Coleman

I found myself fascinated with Dr. McIver’s transition from the stultifying hopelessness of the Segregation Era to the wistful hopefulness of the Civil Rights Era…

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

ELLEN DORNAN

Ellen Dornan serves as the CIO and the Digital Humanities Program Officer. Ms. Dornan has worked with the Council since 2001, serving as webmaster, NHD judge and junior division coach, and a scholar on grant projects and the Centennial Online Atlas of Historic New Mexico Maps. She joined as full-time staff in January 2016.