MARTIN L. KING, JR.'S DAMNING LETTER FROM JAIL

In the letter, King used a multi-disciplinary rhetorical approach that applied philosophical, theological, psychological, sociological, political, ethical and economic principles against systemic racism in Alabama…

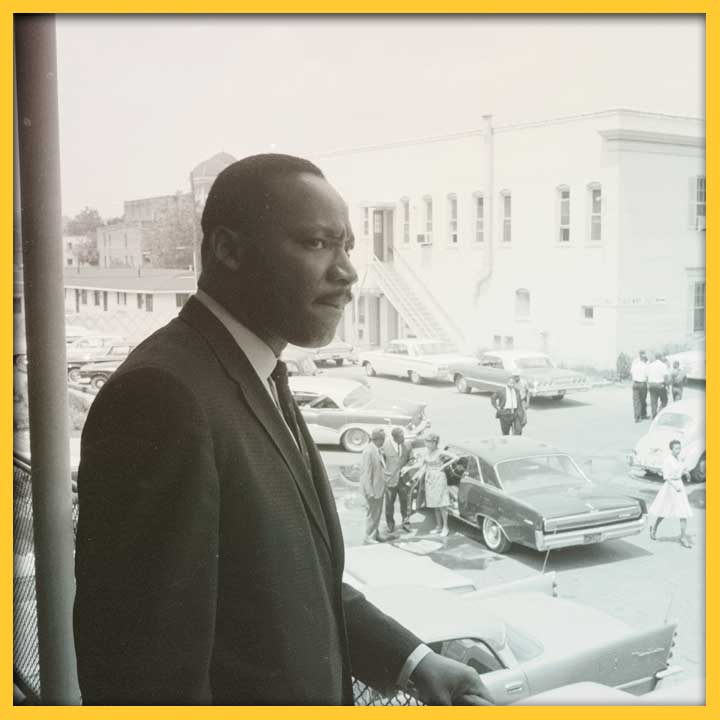

PHOTO CAPTION: Civil rights leader Martin Luther King standing on a balcony at the A. G. Gaston Motel overlooking a parking lot, during the Birmingham Campaign, Birmingham, Alabama. May 16, 1963. Trikosko, Marion S. Library of Congress.

SHARE:

On July 9th, 1868, the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ratified by the U.S. Congress, afforded legal citizenship rights to former black slaves and anyone born within the United States; during this time, northern Union troops were still stationed throughout the South ensuring that violent backlashes against implementing such legislation did not occur. Later, in response to rampant civil rights violations against black citizens, the Civil Rights Act of 1875 was signed by President Ulysses S. Grant; this law prohibited racial discrimination in public accommodations, public transportation, and jury service. However, as a result of the 1896 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in a case titled Plessy v. Ferguson, segregation proponents achieved a victory of sorts over desegregation laws when it became legal to establish separate but equal public accommodations for both blacks and whites throughout the American South. This case would implement one of the most vile economic and psychological warfare campaigns against African Americans during the time frame we would call the Jim Crow Era (1877 – 1964); both black and white American civil rights activists tolerated racial segregation laws, but continually fought for their removal. One key social activist would be a Black Baptist minister named Martin Luther King, Jr.; one of his most potent weapons in the war against racial injustice was his ability to write compelling messages.

In his Letter from the Birmingham Jail (April 16, 1963), King made a reasoned and passionate appeal about the injustice of racial segregation in the American South. Writing the letter on toilet paper to Birmingham-area clergymen, King responded to their criticism about his social activism in Alabama, where he was called an unwise outside agitator. He wrote, “Anyone who lives in the United States can never be considered an outsider anywhere in this country.” King rightly believed it was important to clarify to Birmingham-area clergymen that he was, in fact, invited by others in the Christian civil rights community in Alabama to help place nonviolent pressure to end Birmingham’s racial segregation practices. This pressure was intended to convince the mayor of Birmingham to comply with new federal laws which prohibited racial discrimination practices, such as segregation, in the American South. Moreover, King strongly criticized white moderates’ cries for more time for segregation to end. According to King, moderate whites were not sympathizing enough with blacks living under the humiliation of racial segregation, much less empathizing with them as Christian brothers and sisters; King argued simply that justice delayed is ultimately justice denied.

In the letter, King also asserted that Birmingham-area clergymen actually were themselves unwise in praising the local police department for exercising restraint when dealing with citizens during a recent public demonstration; he argued that to use a moral action like restraint to, ultimately, preserve the immoral institution of racial segregation is the highest form of treason. Unfortunately, restraint on the part of the police would not be applied later in March of 1965 at the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, where hundreds of civil rights marchers would be violently attacked.

To King, it was not inevitable that through the passage of time racial segregation would end, but that its demise must be actively pursued using wise and ethical approaches. Unjust segregation laws are not legitimate for blacks or whites to comply with. Nevertheless, King assumed that without aggressive pressure applied through nonviolent means upon society’s unjust laws and institutions, the experience of equal citizenship between black and all other citizens in the United States would never come about. While King assumed that it is not inevitable that racial segregation will end on its own, he did argue that it is in how we use the time that we have that will end racial segregation practices.

One of the letter’s main motivations seems to be that King wanted to expose the long-term hypocrisy and lack of political support from both the Birmingham-area clergy and moderate civil rights leaders; indeed, these leaders failed to practice empathy for their Judeo-Christian black brethren’s plight by only calling for patience and hope that, over time, Southern racial segregation laws would be overturned. In the letter, King used a multi-disciplinary rhetorical approach that applied philosophical, theological, psychological, sociological, political, ethical and economic principles against systemic racism in Alabama; indeed, King would convey an airtight case against racial segregation and the moral leaders who, to this day, fail to fight against social injustice in their midst and the wider community.

The language and information King used in the Letter from Birmingham Jail to ground his arguments were of an intellectually high caliber. He provided information that was relevant to the racial and political situation in Birmingham, Alabama; generally, about the unjust state of citizenship rights and privileges experienced between blacks and whites there. For example, he cites the Supreme Court decision of 1954 desegregating public schools as one of the key federal laws that the authorities in Alabama were intentionally violating. In the letter, King used relevant quotations from philosophical, theological, political and other social figures to make a more comprehensive case against racial segregation practices in the United States.

King also effectively applies the ideas, concepts and theories established by Saint Augustine, Immanuel Kant, Socrates, Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln to make his case against undemocratic segregation laws. In the letter, King claimed that unjust laws have no legitimacy in a truly democratic society. Indeed, he argued, “Who can say that the legislature of Alabama which set up the segregation laws was democratically elected?” King asserted in the letter that there are good laws and bad laws; the latter type of law is biased, does not allow full participation of all citizens, and does not apply to all citizens equally. He wrote, “I would agree with Saint Augustine that ‘An unjust law is no law at all.’” Therefore, unjust laws must be overturned and better ones enacted in society that are applicable to both majority and minority populations.

A reassessment of civil rights laws pertaining to racial discrimination policies and practices in the United States is one of the key consequences of this letter. In 1964, the Civil Rights Act would be signed into law. This law would end official segregation in public places and banned employment discrimination; King would be one of the witnesses as President Lyndon B. Johnson signed this act into law. The following year, the Voting Rights Act (1965) would extend the voting franchise to African Americans. In April 1968, Martin Luther King, Jr., as he prepared to speak to public sector workers, would lose his life in Memphis, Tennessee to an assassin’s bullet. His dream of the Beloved Community has yet to be realized in the world. A copy of this letter can be accessed here.

The author of this article encourages discussion groups to form during 2025 to discuss this important literary masterpiece, The Letter from Birmingham Jail.

Source: King, Martin Luther, Jr. Letter from Birmingham Jail (Penguin Classics, 2018).

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

NEW MEXICO’S AMAZING BLACK HISTORY

By Rob Martinez, State Historian of New Mexico.

“African history runs deep in New Mexico. Black history is often framed within the institution of slavery, but in New Mexico, New Mexicans of African descent were ambassadors, explorers, colonists, soldiers, cowboys, discoverers, settlers, businessmen, educators, and much more.”

SCANNING FOR STORIES

It was a Friday afternoon in November and I was driving on a state road through the hills of the Mimbres Valley. The entire landscape was bathed in a golden hue because the tree leaves had made their full conversion to a bright yellow color just before falling off the branches.

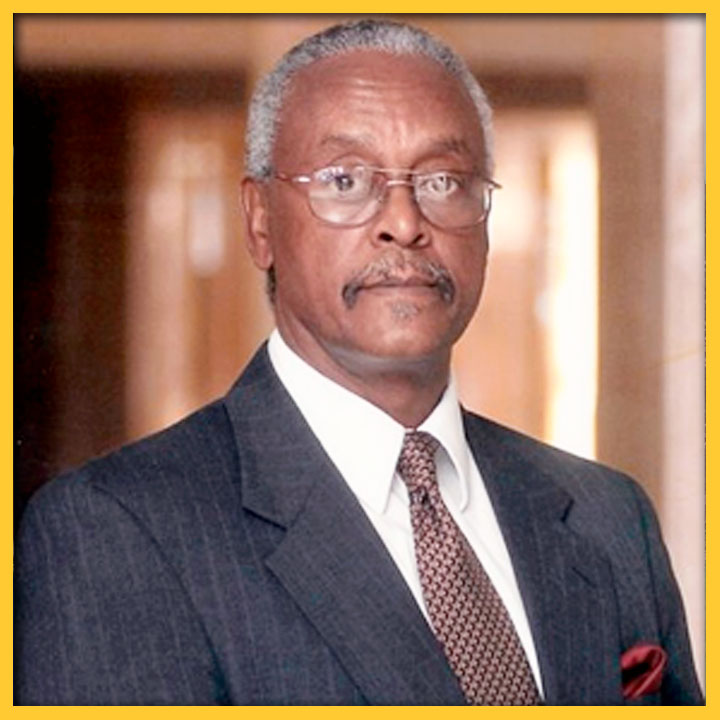

REFLECTIONS ON THE LOSS OF A NEW MEXICO CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER

By Carlyn N. Pinkins, M. A.

“The Dr. Harold Baileys of the world should inspire us all to do what we can to leave our communities, our towns and cities – our great state – better places than we found them. While we do our part to create the Dr. Harold Baileys of the future, we should also strive to make sure that the Dr. Harold Baileys of our past and present are never forgotten.”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

CHRISTOPHER A. ULLOA CHAVES, ED.D.

Chris Chaves works for the University of New Mexico, College of Arts & Sciences; he has years of experience creating and facilitating public humanities seminars involving the intersection of literature, ethics, and social justice. He completed a doctoral degree at the University of Southern California where he investigated the links between English and math courses, student involvement, and academic retention in community colleges. Aside from his administrative experiences, he has taught for the University of New Mexico, the College of William & Mary, Southern Illinois University, and lectured at Santa Fe Institute. He is a member of the Ralph Waldo Emerson Society.