SHARE:

For most Americans, Indians remain the backdrop to American history. Indian heroes are the warriors of the past. Miguel Trujillo was an Isleta Pueblo Indian living at Laguna who directly confronted the bias and prejudice that denied Indians the right to vote in New Mexico. His fight for Indian voting rights made him a hero and a warrior of the mid-20th century.

In 1924, an act of Congress made citizens of all Indians. Nonetheless, the state of New Mexico continued to deny the right to vote in state elections to all Indians, based on the section of the 1912 state constitution which forbade suffrage to “Indians not taxed”—that is, Indians who did not pay taxes on tribal lands which are held in trust status by the United States government. In 1948, Miguel Trujillo decided to fight for his right to vote.

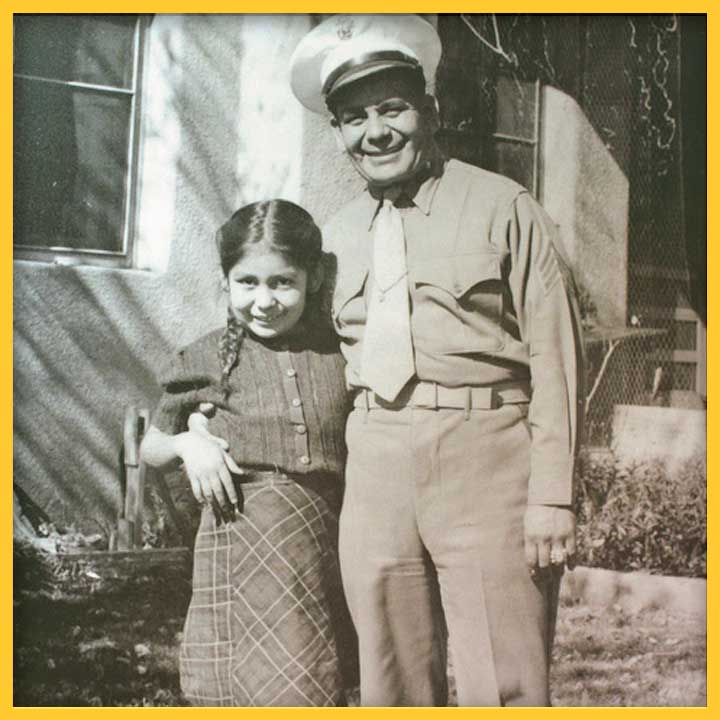

In 1948, Trujillo was an ex-Marine sergeant and teacher at the Bureau of Indian Affairs day school at Laguna Pueblo. On June 14, 1948, he attempted to register to vote in Los Lunas and was refused under the “Indians not taxed” provision. Trujillo and his attorney Felix Cohen, author of the Federal Handbook of American Indian Law, who was then the attorney for Laguna Pueblo, asked the U.S. District Court in New Mexico for an injunction barring the refusal.

Previous attempts to register Indians to vote were unsuccessful. What made Trujillo decide to press the issue further? According to his daughter, Josephine Waconda, Trujillo initiated the legal action to bring equality to the Indian people.

Trujillo’s life showed considerable drive and determination. His father died when he was quite young, so his mother was left to raise the children alone. Trujillo began attending school at the Albuquerque Indian School, which at that time had only 10 grades. As he grew up, family and friends pressured him to quit school to support his family. But he felt an education was essential and continued to attend school.

Trujillo went on to Haskell Institute in Lawrence, Kan. Soon thereafter, he married Ruchanda Paisano of Laguna Pueblo, a member of the Haskell class of 1928. In the meantime, he started teaching at the Bureau of Indian Affairs school at Laguna Pueblo.

Miguel began taking classes at the University of New Mexico. There were no scholarships available for Indian students at that time, and he was supporting his wife, their two children and his elderly mother as well. Nonetheless, after years of dogged persistence, Trujillo finally received his bachelor’s degree — just in time for the onset of World War II.

Like many other Indians, Trujillo enlisted in the Marines, ultimately becoming a staff sergeant. After receiving an honorable discharge at the end of the war, he returned to his family and his teaching post at Laguna, commuting regularly to Albuquerque to earn his master’s degree on the GI Bill.

What was it about the postwar situation in New Mexico that encouraged Indians – and Trujillo in particular — to push for the right to vote? The times were changing. In 1947, the Report of the President’s Committee on Civil Rights condemned disenfranchisement of Indians in New Mexico and Arizona, noting that Indians were citizens and subject to both federal and state taxes, except for lands in trust status. The committee recommended that New Mexico and Arizona grant suffrage to their Indian citizens.

Attempts by Indians to gain voting rights also attracted great public support because Miguel Trujillo was a veteran, representative of the thousands of American Indians who served in World War II. At the same time, the Cold War was beginning, and it was increasingly difficult for the United States to condemn Communist regimes for mistreatment of their citizens while American citizens were denied equality because of race and color.

A three-judge panel was appointed to rule on the injunction sought by Trujillo and his attorney, Felix Cohen. They argued that the constitutional provision excluding “Indians not taxed” violated the 15th Amendment to the United States Constitution, which states, “the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

As part of their case, they noted that the plaintiff Trujillo and other Indians paid a variety of taxes, such as income and sales taxes — all taxes except those on trust status lands. The attorneys argued that denial of the vote to Indians violated the equal protection clause because New Mexico permitted untaxed black and white citizens to vote. Further, they stated that Congress had ruled that the policy of declaring “Indians not taxed” was obsolete on precisely the grounds that Indians did pay taxes and that, because of this decision, New Mexico’s Indians were counted in the 1940 congressional apportionment, which resulted in an additional congressman for the state.

On Aug. 3, 1948, the presiding judge delivered the decision for the panel. ‘The court ruled that those portions of the New Mexico Constitution that denied the right to vote to Indians were unconstitutional and void. After 36 years of statehood, New Mexico was forced to grant its Indian citizens voting rights in state and local elections.

The decision received favorable attention across the country. Miguel also was given an award of appreciation by the people of Laguna.

Nonetheless, the name of Miguel Trujillo has faded away. Why? Perhaps as his daughter Josephine said, “His time came late.” The late 1940s and early 1950s saw a major push by the federal government to relocate Indians to urban areas and terminate reservations in an attempt to “bring them into the mainstream.” Trujillo’s defense of Indians and Indianness at meetings of the All-Indian Pueblo Council and elsewhere led to pressure from his superiors in the Bureau of Indian Affairs, including a threat to transfer him to South Dakota.

But by this time, Trujillo’s mother was in poor health, and fearing the consequences of a move, Trujillo softened his outspoken defense of Indians. He and his family were transferred to Intermountain School in Brigham City, Utah, where he remained until he retired in 1959.

After retiring from the BIA, he returned to Laguna. Although his time may have come late, Miguel Trujillo remains one of the great civil rights pioneers of New Mexico.

I want to acknowledge Miguel Trujillo’s family for sharing his story with me, especially his daughter, the late Josephine Waconda.

This column was generously funded by a grant from the Mellon Foundation to explore the question of Democracy and the Informed Citizen.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

REFLECTIONS ON THE LOSS OF A NEW MEXICO CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER

By Carlyn N. Pinkins, M. A.

“The Dr. Harold Baileys of the world should inspire us all to do what we can to leave our communities, our towns and cities – our great state – better places than we found them. While we do our part to create the Dr. Harold Baileys of the future, we should also strive to make sure that the Dr. Harold Baileys of our past and present are never forgotten.”

RUDOLFO ANAYA: CATCHING CULTURES IN BLESS ME, ULTIMA

By Richard Wayne Etulain

Anaya greatly expands the cultural contributions of his novel by combining the usual (Bildungsroman—growing up theme) with the unusual (complex, diverse New Mexico Hispanic culture)…

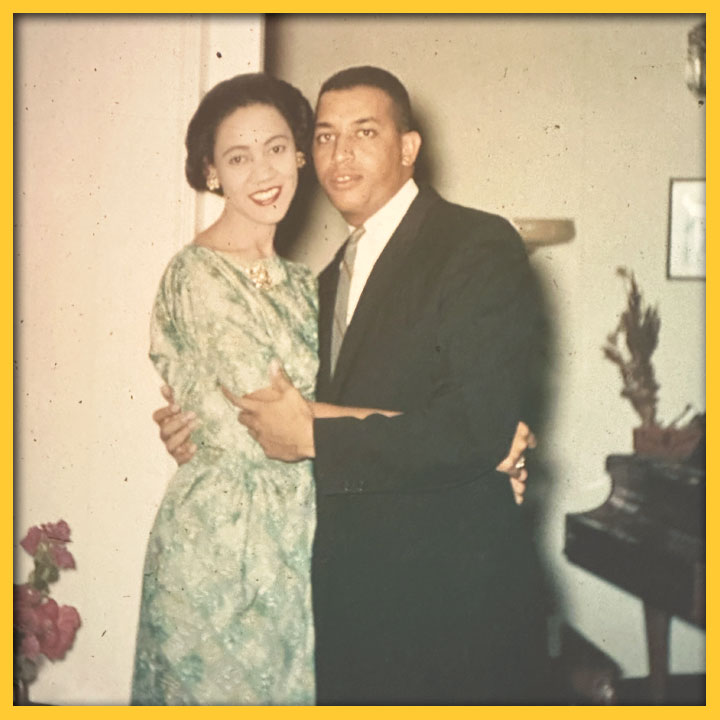

UP BY OUR BOOTSTRAPS; TWO LIVES IN RETROSPECT

By Finnie Coleman

I found myself fascinated with Dr. McIver’s transition from the stultifying hopelessness of the Segregation Era to the wistful hopefulness of the Civil Rights Era…

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

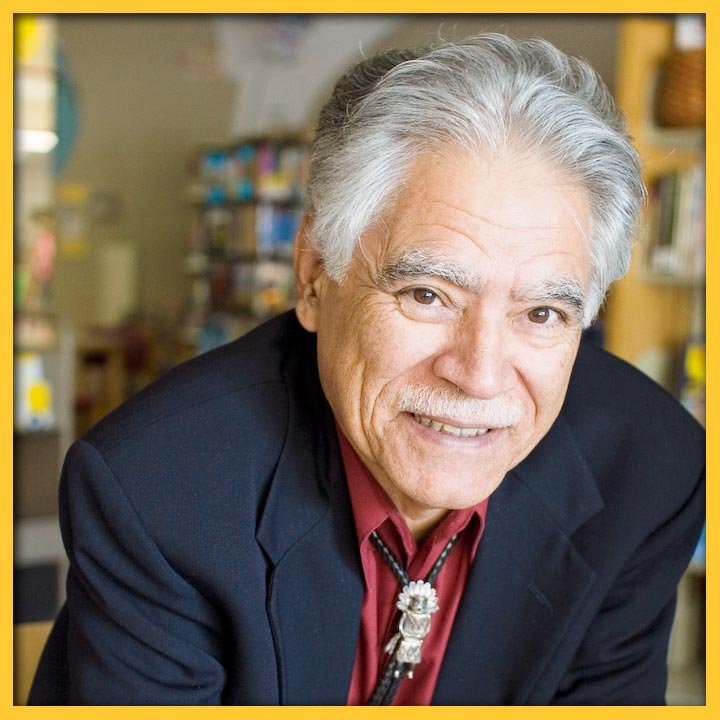

GORDON BRONITSKY

Gordon Bronitsky grew up in Albuquerque and is an anthropologist by training (BA UNM, 1971; PhD University of Arizona 1977). For the last 27 years, he has been founder/president of Bronitsky and Associates dba IndigeNOW!, its non-profit production arm. IndigeNOW's mission is simple – to work with Indigenous artists and performers, traditional and contemporary, to bring their voices and messages to the world. You can learn more about his work at indigenow.com.