SHARE:

With thanks to Aquinas, Descartes, Kant, Camus, Plato, Rousseau, Kafka and Saint-Exupery

© Elaine Carson Montague 2023

How do we celebrate what it means to be human?

Are we human when the Office of the Medical Examiner says the body bag cannot be unzipped for a final goodbye? We stand in midnight’s blackness of sudden death at an assisted living facility, and I hear the explanation, “Sorry, we can’t do that: COVID rules!”

What does humanity mean in American society? How important to maintaining good quality of life are communication and the way we treat one another?

Philosophers suggest that we are human because we think or reason. Thus, I question.

Let us reflect upon our elderly, infirm and disabled. Must we act humanely to be called human? We say our republic is a democratic society. Democratic is a synonym for humane. Our actions affect what others think and do. Hindu actress Priya Mishra in The Times of India Readers’ Blog reminds us to understand and respect the positive value of every being, to learn from mistakes and improve, and to contribute to making the world better. What will we learn from the COVID-19 pandemic? To show compassion, be benevolent, act mercifully with kindness?

Is it ethical to do another’s thinking and issue mandates contrary to most people’s sense of right and wrong? Even when fear of the unknown forms the basis for such rules or when great debate ensues and haste encourages flight from the threat of collective danger, is it moral? Such regulations constrain the few and offer a dilemma over which they have no control. If the dilemma is likely to end in physical death or a surcease of communication and loss of all they love only to take more breaths, is it OK?

Who should have control and make decisions? What role does freedom of personal choice play? What is the role of the state vs. personal responsibility?

As we seek to interpret a new world amidst the onslaught of death and confusion such as during the COVID-19 pandemic from 2020 to 2023, how do we make sense of an upturned society, impacting people nationally and worldwide? During the pandemic, voices rose around us in protest, both personal and societal, and expressed differing opinions, from obtuse and illiterate to knowledgeable but with differing assessments. The grieving and frightened populace could not discern truth in a time of unsureness.

A pandemic affects a substantial number of people. In the case of COVID-19, it resulted in great losses of life, global socioeconomic upheaval and widespread grief.

In my life, it tore apart a union of more than six decades and caused loss of personal and medical care for the human being I loved most during all that time. His heart pumped. His lungs brought life-giving breath. I felt his touch sweep love to every tiny nerve in my body. His laughter and infectious grin warmed me. His spirit sustained me. He was real.

The calls came. “You cannot come back. We are on lockdown. No visitors are allowed.”

“He must remain in his room and no longer see other residents.”

“His private nurse cannot come, nor his therapists. You are all locked out.”

My husband had little sight and lived in an assisted living facility that did not want him to leave for any reason for fear that he might bring back a dread disease. Medical treatment for a serious underlying condition and therapy to restore walking stopped. I was not there to read aloud and offer comfort. Employees were free to come and go, required only to say that they had not encountered anyone with COVID or experienced symptoms, but he was isolated from his caregiving family and fellow residents. Oxford Learner’s Dictionary says, “Contact with other people is a basic human need.”

For eight months, we celebrated holidays, birthdays, and a precious anniversary by phone and tablet and were far more than socially distanced. He had trouble managing a device with no tangible buttons or bright markings. Was it right side up or askew, as our world had become?

State ombudsmen were not allowed to enter facilities to ensure residents’ care, leaving families unable to monitor the care of loved ones. The state sent my husband to a COVID rehab center, where I felt that caregivers did not understand what low vision means, adding to his fear and frustration. He also encountered broken or disconnected plumbing, confusion about where his clothes were, lack of warm blankets, and poor communication. He was asymptomatic. He asked me to get him out of there alive. I did, but he lived only days longer.

There were moments when I felt powerless to affect our destinies. Mostly, I felt very alone in the struggle, begging God for help.

As I seek to forgive those responsible for what happened and walk in the unfamiliar territory of aloneness, how do I sort through conflicting personal feelings and chaos? How do I grieve physical and emotional loss and understand my obligation to our social contract? Do I rely only on my strong religious faith, or might I find societal threads to restore strength and resilience?

The state is a form of human association to establish order and security, as well as mental state. Plato taught that man reflects the character of the state he lives in. He said that safety and belongingness are among basic human needs that motivate us and we are here to help one another.

Nelson Mandela said, “It is during our darkest moments that we must focus to see the light.” Will we learn and improve from the darkness of COVID-19?

How important is informed citizenry when facing sudden onslaught by a threat of unknown origin with unpredictable outcomes? How do we retain habits, customs, and beliefs that protect our life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness? What do we believe about being human?

Indeed, I have more questions than answers. Hence, the need for brave leaders and journalists who value the importance of our being informed.

We have user-friendly tools for fast communication and the financial access to those tools. How do we use them to celebrate what it means to be human? Do we stimulate discontent to awaken understanding and relieve human suffering or stimulate discontent because we can? Are we free to ask questions without fear of excoriation by those with strong differences of opinion?

With all the noise around us, will we be an informed citizenry?

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

NEW MEXICO’S AMAZING BLACK HISTORY

By Rob Martinez, State Historian of New Mexico.

“African history runs deep in New Mexico. Black history is often framed within the institution of slavery, but in New Mexico, New Mexicans of African descent were ambassadors, explorers, colonists, soldiers, cowboys, discoverers, settlers, businessmen, educators, and much more.”

SCANNING FOR STORIES

It was a Friday afternoon in November and I was driving on a state road through the hills of the Mimbres Valley. The entire landscape was bathed in a golden hue because the tree leaves had made their full conversion to a bright yellow color just before falling off the branches.

REFLECTIONS ON THE LOSS OF A NEW MEXICO CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER

By Carlyn N. Pinkins, M. A.

“The Dr. Harold Baileys of the world should inspire us all to do what we can to leave our communities, our towns and cities – our great state – better places than we found them. While we do our part to create the Dr. Harold Baileys of the future, we should also strive to make sure that the Dr. Harold Baileys of our past and present are never forgotten.”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

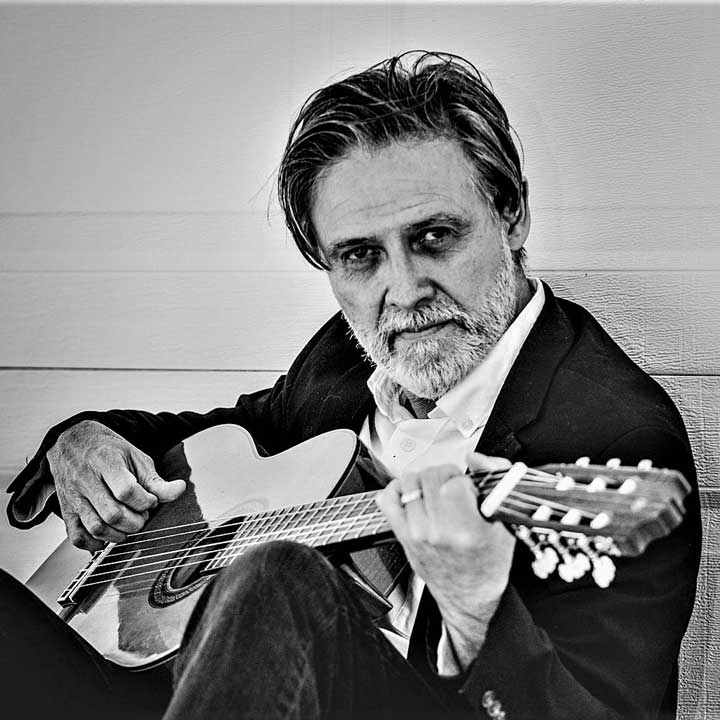

ELAINE MONTAGUE

Elaine Carson Montague is a career educator, an award-winning author and poet who wrote “Victory from the Shadows, Growing Up in a New Mexico School for the Blind and Beyond” with her late husband, Gary Ted Montague. They set a goal that the book be read in teacher-training programs in the English-speaking world. Victory has won eight literary awards, including two international ones. Elaine (www.elainemontague.com) is a member of SouthWest Writers, New Mexico Press Women, and New Mexico State Poetry Society. She cherishes sunsets, open space, Bible study, and time with friends.