SCANNING FOR STORIES

It was a Friday afternoon in November and I was driving on a state road through the hills of the Mimbres Valley. The entire landscape was bathed in a golden hue because the tree leaves had made their full conversion to a bright yellow color just before falling off the branches.

Moonrise over Mimbres Valley.

Photo courtesy of Bethany Tabor

SHARE:

It was a Friday afternoon in November and I was driving on a state road through the hills of the Mimbres Valley. The entire landscape was bathed in a golden hue because the tree leaves had made their full conversion to a bright yellow color just before falling off the branches.

I was leaving the Mimbres Cultural Heritage Site (MCHS) after completing an underground scan of the archaeological remains as part of the Cultural Scans for Interactive 3D Experiences (SITEs) digital preservation project. After spending four days in the field exploring the site and learning about its history from the staff and volunteers who steward it, my drive was consumed by thoughts and reflections on things like place and history, the value of preservation, the concept of deep time. The MCHS sits atop a vast Classic Mimbres that was occupied between 1000–1150 A.D.

Driving away from the site and moving through the landscape, I thought about the Mimbres people and all the other people who have occupied this land hundreds and thousands of years before me. I imagined the experiences of the people who trod this land centuries ago and what daily life must have felt like; what daily living meant when there were no industrial tools like we have now, without electricity and how humanity lived within the cycles of the natural light of the Sun and Moon and the other celestial orbs of light. My vision of that ancient time was vivid and I could even hear the bustling scenes from Mimbreño life in my mind. It was the most alive that history had ever felt to me. Next, my thoughts wandered to what it would be like if anyone from that time period could see what life on Earth has developed into. Likely, they’d be struck by awe and perhaps even horror at the civilization we’ve built. I wondered whether they would have ever in their wildest imaginations anticipated their homes and buildings and ceremonial kivas would be dug up and examined by people living in the same place a millennium after them. I wonder what our own monuments and buildings will look like to humanity a thousand years from now. It was at this moment in my thought spiral that I realized that in the day-to-day living of the Mimbres people, they were not thinking of the burial of their built environment; nor were they thinking that their way of life would be temporarily obscured and rediscovered hundreds of years later. Again, I applied this to my own life and questioned what about my quotidian joys and worries that seem so important to me now will be completely forgotten with the passage of time. Everything that seems of enormous consequence to us now will eventually pass away, which can be a soothing thought for some. On my drive through the valley, however, I realized that there were ancient people like me, like us, cultivating and taking care of this same land who experienced stress and excitement and sorrow and ecstasy every day of their lives. Their individual experiences have been “forgotten” in some sense, but they weren’t inconsequential—in fact, these small experiences make up the tether that holds humanity together in historical procession and progression. At that moment—I was driving around a bend in the road and the hills around me opened up to a vast expanse of prairie—the monumentality of the human experience loomed before me and overwhelmed my emotions. I felt a profound urgency for documenting and recording everything for posterity, so that no one would ever feel as if their individual lives were so unimportant that they would inevitably be forgotten.

This exaggerated sentimentalism passed over me quickly, but the general feeling and insight has stayed with me as I continued to devote my time and work toward the Cultural SITEs digital preservation project in New Mexico. The intensity of the moment reminds me why history and preservation are valuable: if we are not conscious of the continuous story of our humanity, we’d likely never consider the weight and importance of our lives and decisions and the impact they have on the future.

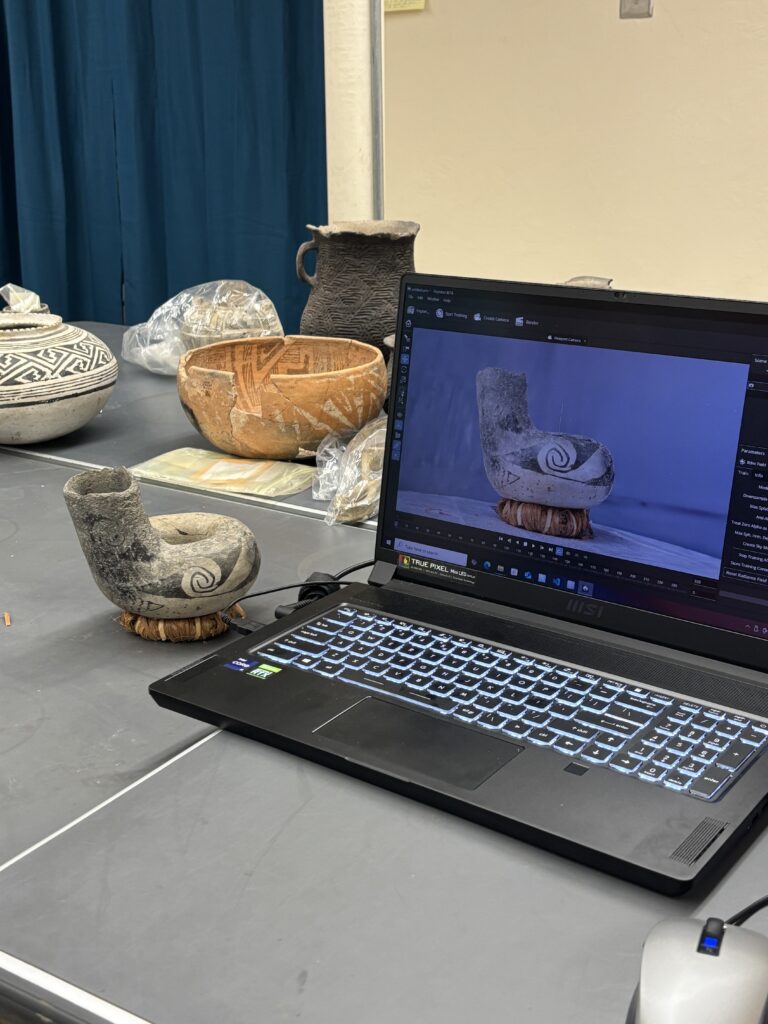

Cultural SITEs began in 2023 as a vision to document historic sites around New Mexico using various 3D scanning techniques and preserve these sites digitally, which would allow people to interact with them in the digital and virtual realms. The understanding is that the digital space is practically infinite, with a myriad of ways to create a greater depth of study and interaction with historic sites. Digital preservation is not an attempt to usurp material preservation and conservation, nor to replace the physical sites, but meant to abet historic education, access and research. What I set out to do was access cutting–edge imaging technology and get it into the hands of the various historians and archaeologists who manage and supervise the state’s treasures to highlight our state’s rich heritage. As I was seeking funding for this project I was connected to a team of scientists and engineers at Northrop Grumman’s Technology for Conservation (NG T4C), which is a program at Northrop Grumman that seeks to leverage their tools and technology for environmental and cultural conservation. This team, led by my esteemed colleagues Dr. Jennifer VanBerschot and Zac Van Note, had the same goals in mind for their next conservation project: to use 3D scanning technology to document the built environment in New Mexico. The scope and extent of the work that we’ve done in two years would not have been possible without the dedicated NG T4C team. Their effort and expertise have led to innovations in the space of digital heritage that has changed New Mexico’s historic sites for the better.

In two years, the Cultural SITEs team covered five sites from different historical periods and in varying degrees of preservation. Some sites had standing, or fully excavated, structures; others, like the MCHS, had structures entirely underground; one had only a few remains still standing and eroded. The scope of each one of these sites is enough to fill several volumes of history books, and each story that they tell contributes to the intricate tapestry of human civilization in this part of the world. We used different technologies at each site as we tried to figure out what the most pressing preservation needs were for each individually.

For our first scan, the SITEs team visited Fort Selden in Radium Springs, N.M., and stewarded by the State’s New Mexico Historic Sites (NMHS) agency. A 19th Century fort constructed mostly out of adobe, the remains at Fort Selden are eroded with the only standing structures being walls that stand about eight feet tall. We documented these structures using photogrammetry, which is a method that captures several images of an object from all angles which are then digitally stitched together to create a 3D, digital render of the object. This digital render is interactive through a desktop computer and AR and VR applications. Furthermore, using the photogrammetric data plus a host of archival photographs and blueprints from Fort Selden, the NG T4C team created a digital reconstruction of the fort as it looked when it was in use.

Photogrammetry and 360° imaging techniques were also used at Lincoln Historic Site in Lincoln, N.M., (also managed by NMHS), MCHS in Mimbres, NM, and Salmon Ruins in Bloomfield, N.M. At each of these sites we captured photogrammetric data on the exterior and interior of the standing structures and created a digital museum experience complete with interpretive language provided by the staff and managers of each site. The digital interactivity made possible by these 3D scans provides a whole new level of access for visitors who face any number of challenges to visit the physical locations. The virtual museum experiences available at Lincoln have already allowed the site to develop distance learning programs for schools in New Mexico that are hundreds of miles away and cannot afford to travel to Lincoln.

In addition to interactive digital models used for education, we also used photogrammetric data to create a 3D printed model of the Spanish Colonial Torreòn in Lincoln, one of the last remaining Spanish torreòns in New Mexico. The 3D printed model, measuring at about 9in. by 9in., is a handheld replica of the structure that is on display on the New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs’ Wonders on Wheels traveling exhibit. Wonders on Wheels travels to different rural communities throughout the state to provide students with hands-on learning experiences in history and social studies. The students can open up the 3D printed Torreòn to see a cross-section of the building, making for an even more interactive learning experience.

We continued artifact scanning work using photogrammetry at Salmon Ruins, which is a Chaco Outlier archaeological site managed by San Juan County. For the artifact scans here, the NG T4C team used a cutting-edge rendering technique, called Gaussian splatting, to create high resolution 3D digital replicas of a selection of objects in the Salmon Ruins Museum’s collection. These digital renders will also be used for educational purposes and to create an enhanced and interactive experience with the objects that everyday visitors wouldn’t otherwise have access to.

For the sites with structural remains underneath the ground, we used spectral imaging techniques to explore below the surface to provide further research to archaeologists studying these sites.

Sevilleta Pueblo, in La Joya, N.M., is a pueblo built by the Piro people and later settled by the Spanish. Piro Pueblos were located along the Rio Grande Valley in and around the city now called Socorro, N.M. The Piro population would eventually split and assimilate with different tribes in southern New Mexico in the late 18th Century; their archaeological remains are some of the only remaining material culture of the Piro. Dr. Michael Bletzer is the archaeologist who has dedicated his time and effort to studying Sevilleta Pueblo located about 15 miles north of Socorro. For Cultural SITEs we used light detection and ranging (LiDAR) to scan the site to create digital terrain maps that could answer some longstanding questions about how Sevilleta was used, especially in relation to the Camino Real Spanish trading route, and also to track environmental changes over time to the site.

Other spectral imaging techniques used by Cultural SITEs was ground-penetrating radar (GPR) and magnetometry to study the Mimbres archaeological remains at MCHS. The Mimbres site has been excavated twice in the 20th Century—in the 1930’s and 1970’s—but has been backfilled and with a large portion of the site entirely un-excavated. What we had hoped to find with the GPR and magnetometry scans would be evidence of structures below the ground extending further north of the land that was excavated. Due to extensive vegetation in the area disrupting the sensors on our radar, we were unable to locate structures. However, we were able to scan the previously excavated land and provided heat maps of the structures to further enhance visitors’ understanding of the site. This is in addition to the virtual museum experience we provided of the museum at MCHS.

The value of these digital scans and renders is nearly immeasurable as the portal of access to New Mexico’s history has been widened for new discoveries and new educational opportunities are created. The project was a great success in this regard and I am astonished at the dedication of work and effort put forth by the people managing and studying these sites, as well as the engineers at Northrop Grumman who poured their knowledge into making this digital preservation project a reality. What remains most meaningful to me in all of this is the time I got to spend at each of these locations and the amount of history I absorbed about each. Humanity is ultimately the sum of our stories, which we pass on through our monuments, our traditions, our art and our craft. Preservation and documentation build an archive which functions as a parallel monument that stores this collective experience. The archive-monument is the wellspring from which we draw information and inspiration to carry on our story, and it has been the honor of my career at the Humanities Council to contribute to it

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

NEW MEXICO’S AMAZING BLACK HISTORY

By Rob Martinez, State Historian of New Mexico.

“African history runs deep in New Mexico. Black history is often framed within the institution of slavery, but in New Mexico, New Mexicans of African descent were ambassadors, explorers, colonists, soldiers, cowboys, discoverers, settlers, businessmen, educators, and much more.”

SCANNING FOR STORIES

It was a Friday afternoon in November and I was driving on a state road through the hills of the Mimbres Valley. The entire landscape was bathed in a golden hue because the tree leaves had made their full conversion to a bright yellow color just before falling off the branches.

REFLECTIONS ON THE LOSS OF A NEW MEXICO CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER

By Carlyn N. Pinkins, M. A.

“The Dr. Harold Baileys of the world should inspire us all to do what we can to leave our communities, our towns and cities – our great state – better places than we found them. While we do our part to create the Dr. Harold Baileys of the future, we should also strive to make sure that the Dr. Harold Baileys of our past and present are never forgotten.”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: