SHARE:

80 years ago, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 that began an irreversible tidal wave of racial prejudice towards Asians, particularly those who were Japanese. Issei and Nissei were first- and second-generation Japanese and Japanese Americans living in the U.S. Their leaders, scholars, priests andfishermen were rounded up immediately after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941. They were forced into relocation centers because they were deemed a threat to national security. Soon after, their families were transported to other camps, never knowing the whereabouts of the men who were arrested. My relatives ended up in Santa Fe, Lordsburg (NM), Poston (AZ), Tule Lake (CA), Topaz (UT) and Crystal City (TX), to name a few.

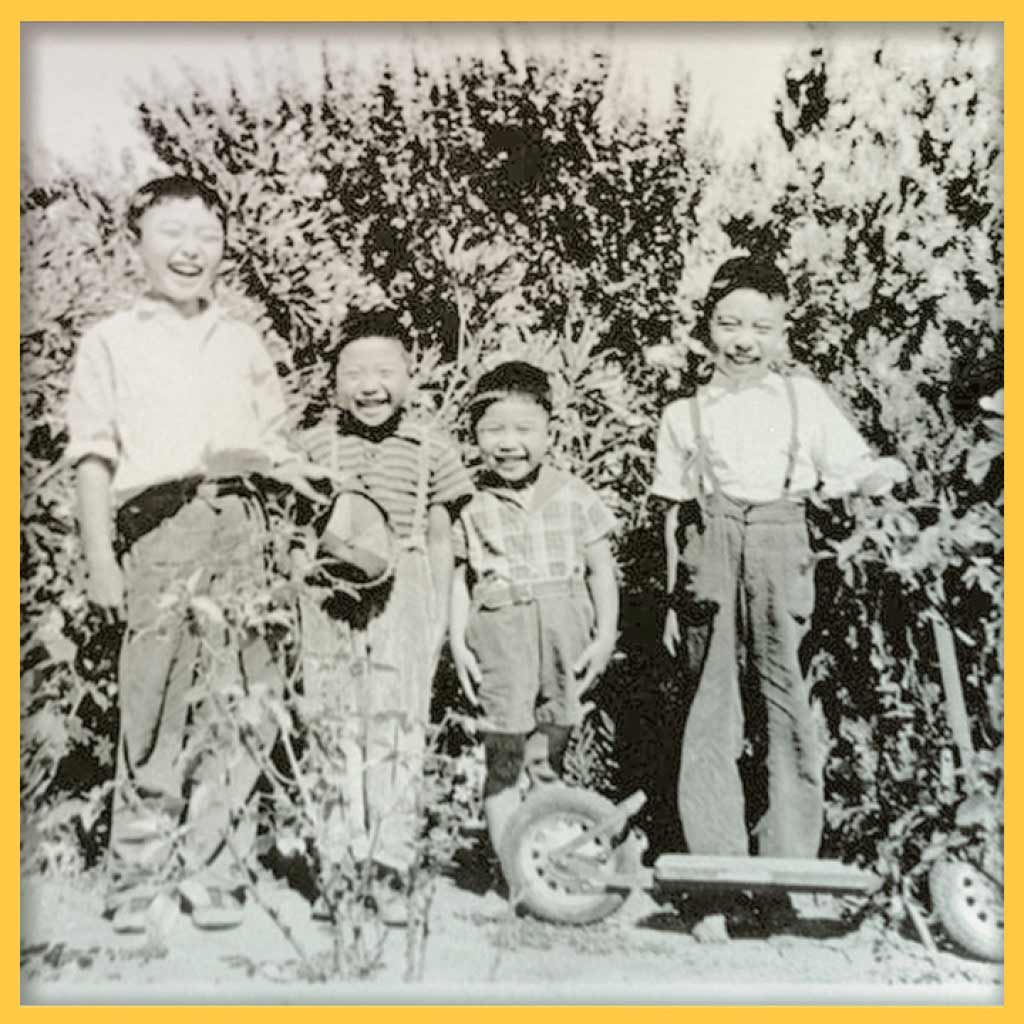

The four boys shown in the photograph watched as their father was taken away to a Department of Justice (DOJ) camp in Santa Fe. Their three older siblings (not shown) were sent to three different camps, mostly due to the fact that they were born in Japan. The youngest boy shown, Mamoru, is my father-in-law. The mother of this family and these boys were sent to Topaz, Utah, and then to Crystal City, Texas, the family camp.

Kiwa, the mother, took care of the boys as best she could, but finally succumbed to diabetes due to poor health facilities and inadequate medicine. The government, in its ultimate wisdom, decided to release the boys’ father, Jingo, from the Santa Fe camp so he could be sent to Crystal City to care for the boys, who were now motherless.

About a year after the war ended, those who were forcibly removed from their homes and imprisoned in the internment camps were finally released without ever being charged with any crimes. My family reunited in California, but their lives were changed forever.

In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed into law the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which officially apologized for the internment on behalf of the U.S. government and authorized reparation to each former internee who was still alive. Jingo and Kiwa had passed away long before this act went into effect, as did many of those who suffered during their imprisonment.

May is now designated as Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) Heritage Month. What began in 1978 as a seven-day tribute, was expanded into a month-long observance in 1990 and into Public Law 102-450 in 1992. This month was chosen to commemorate the immigration of the first Japanese to the United States on May 7, 1843, and to mark the anniversary of the completion of the transcontinental railroad on May 10, 1869. Many immigrants sweated to make this coast-to-coast railway a reality.

The United States of America, like many other countries, has made grievous errors throughout its history, but generally admits its mistakes and strives for justice and freedom for its people. It is often recognized as a welcoming country where people come to make a new start in life; a place for fulfilling new hopes and new dreams. The class system lines of other countries become blurred as new workers come to fill a need for workers and strive for success.

Lady Liberty still stands tall in New York harbor welcoming people immigrating to America as they enter through Ellis Island. On the West Coast, Angel Island in San Francisco Harbor was the entry port where most of the early Asian/Pacific Islander people arrived and were registered after sailing across the Pacific Ocean.

Jingo brought his wife and three oldest children out of Japan to settle in Oakland, California, as he looked for a better, safer life for his family. After World War I, the people of Japan were suffering due to the Depression, food shortages and little chance for employment. America looked like a shining light, rich with new opportunities. Jingo taught school and the family grew in this new land.

After the war, He left behind the memories of the Santa Fe Internment Camp, the Lordsburg Camp, and his unjust arrest. He lost everything during World War II, except his desire to provide a better life for his children. His ancestors learned to carry on despite prejudices and still strive to make the world better by telling their stories, one tale at a time.

The New Mexico History Museum in Santa Fe recently hosted a symposium discussing the Santa Fe Internment Camp (SFIC) where Jingo was detained, the controversy that arose when Japanese Americans sought to place an historical marker overlooking its location, to hopefully help heal the wrongs of the past and bring peace to the present through Tsuru for Solidarity and other reconciling projects. A pilgrimage to the SFIC marker followed the event. For more information please visit Stories, Memories and Legacies.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

REFLECTIONS ON THE LOSS OF A NEW MEXICO CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER

By Carlyn N. Pinkins, M. A.

“The Dr. Harold Baileys of the world should inspire us all to do what we can to leave our communities, our towns and cities – our great state – better places than we found them. While we do our part to create the Dr. Harold Baileys of the future, we should also strive to make sure that the Dr. Harold Baileys of our past and present are never forgotten.”

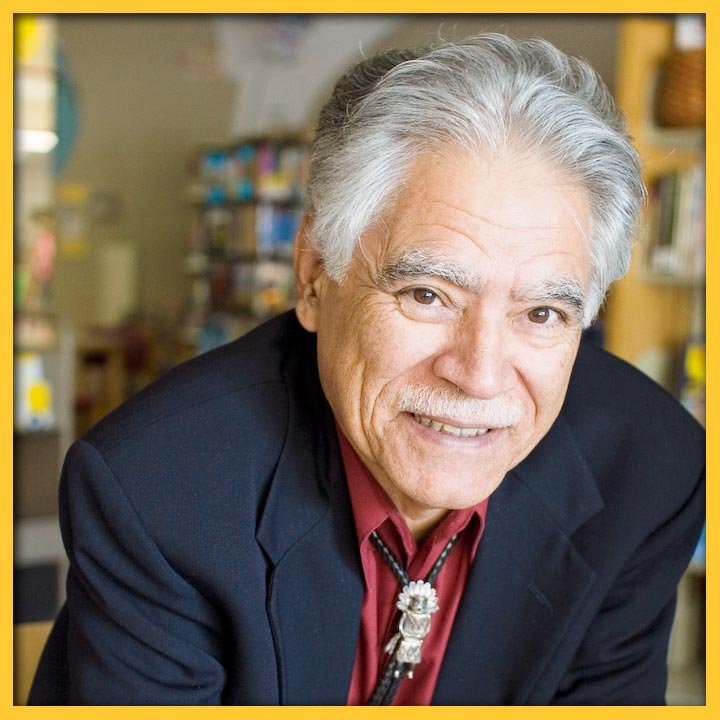

RUDOLFO ANAYA: CATCHING CULTURES IN BLESS ME, ULTIMA

By Richard Wayne Etulain

Anaya greatly expands the cultural contributions of his novel by combining the usual (Bildungsroman—growing up theme) with the unusual (complex, diverse New Mexico Hispanic culture)…

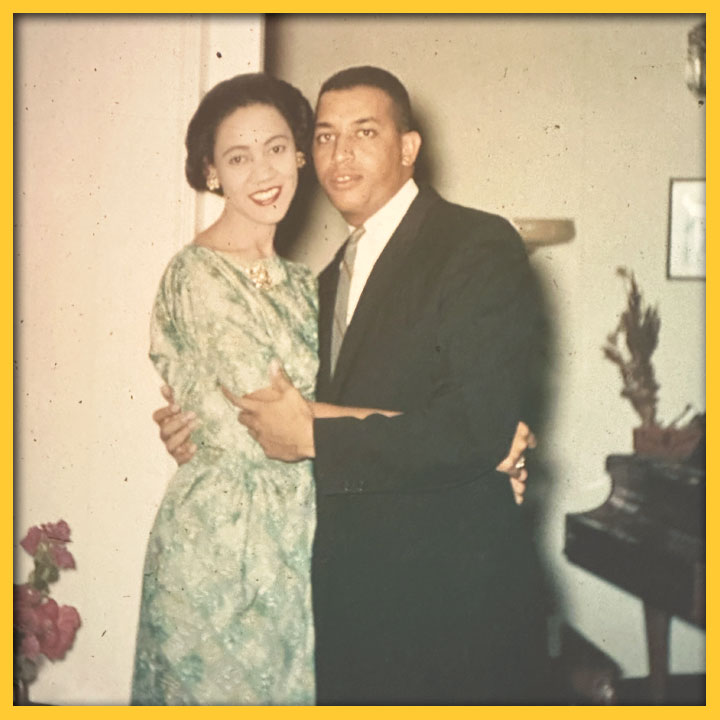

UP BY OUR BOOTSTRAPS; TWO LIVES IN RETROSPECT

By Finnie Coleman

I found myself fascinated with Dr. McIver’s transition from the stultifying hopelessness of the Segregation Era to the wistful hopefulness of the Civil Rights Era…

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

SHELLEY TAKEUCHI

Shelley Takeuchi is a retired teacher, librarian and technology trainer from California. She volunteers with the New Mexico Japanese American Citizens League and is an avid reader, quilter and crafter.