SHARE:

Wintertime in New Mexico is unique. The relatively mild weather, the smell of pine-scented woodsmoke in the air, the farolitos and luminarias

Red chile gravy is part of the Thanksgiving meal for every New Mexican I have ever known, including my own family. Green chile is roasted, peeled, bagged and frozen in the late summer or early autumn for use throughout the winter and spring, usually hoarded in that second freezer that many of us have just for the purpose of having a perpetual stash on hand. In my house in the winter, this frozen treasure makes a regular appearance in one of my favorite family recipes, green chile stew.

The methods of making green chile stew are as varied as the culture and people of New Mexico itself. Some folks stick to the most well-known tradition and use pork. Some families prefer beef or even lamb. Others omit the meat entirely for a vegetarian version. Flour is sometimes used to thicken the liquid into a gravy sauce. The addition of chicken broth, beer or wine is always a welcome augmentation to the hot water generally used as the stew base.

Most New Mexico restaurants have some version of green chile stew on their menus, and here in Albuquerque, many a late night has ended with a Styrofoam bowlful of steaming-hot green chile stew from institutions like The Frontier or Golden Pride. There is nothing like a bowl of Frontier green chile stew, lavishly studded with chunks of meat and potato and the pungent scent of green chile wafting up your nose to blast away the cobwebs of one too many last-call cocktails. It’s an example of being able to take a dish that is a staple of New Mexico family food and turn it into a dish that anyone and everyone can enjoy on a regular basis.

In my own family, my Nana Jean passed her recipes down in a cookbook she made for all of her grandchildren, detailing the variety of home-cooked meals that she cooked on a regular basis and that we all adored. More generic recipes such as rum cake, chocolate-chip cookies, and rice pudding were combined with traditional New Mexican dishes like enchiladas, caldito, nati

Stews are found in every single culture throughout time. After all, there is no easier way to stretch a pricier ingredient such as meat than to combine it with less expensive vegetables such as potatoes, onions, garlic and tomatoes, add some liquid such as water, broth or even beer, and cook it over low heat for several hours. In rural and agrarian communities, the making of stews was an essential way to feed large families while also utilizing the food harvested on the farm. As well, the method of low, slow cooking dates back thousands of years and actually contributed to the invention of the Crock-Pot itself, which is frequently used to make green chile stew.

According to the Smithsonian Magazine, the Crock-Pot first made its appearance in the 1950s, an invention created by a Jewish immigrant named Irving Nachumsohm, originally from the Lithuanian village of Vilnius. Vilnius was once regarded as the “Jerusalem of the North,” where the many Jewish families who lived there readied for the Sabbath by preparing stews made up of meat, beans, and vegetables in earthenware crocks. These crocks would be taken to the town bakeries where the stews would cook slowly overnight in the hot ovens. Nachumsohm, who later changed his name to Naxon when he immigrated to the United States, had learned of this cooking method from a relative, and put his engineering and scientific mind to work inventing a modern slow cooker. The end result was the Crock-Pot that we know and use today.

My own method of making green chile stew has evolved from the recipe given to me by my Nana. Rather than use a Crock-Pot to achieve that slow burn that long, low cooking comports(?) to a stew, I instead cook mine in a huge stock pot over a very low flame for up to seven hours. At its heart, this dish retains the base of meat, potatoes, onion, and green chile cooked in liquid. However, as all recipes should, mine has its own additions that make it both an homage to the original and a unique dish that reflects the taste of the cook. I am not a huge fan of pork, so I use chicken instead. I use homemade chicken stock as the liquid base and I always add a cup of white wine. Being a garlic lover, I add 10 chopped cloves, and a packet of Lipton onion soup mix augments the taste. But to me, it’s that lengthy simmer time that gives green chile stew its richly unique flavor. This is how I make mine.

Dice a large onion and six cloves of garlic and brown them in olive oil. Cube six boneless, skinless chicken thighs and brown them with the garlic and onion. Add two cans of chopped tomatoes and three heaping cups of chopped green chile. Pour over five cups of chicken broth and a cup of white wine, add in a packet of Lipton’s onion soup mix, and add salt and pepper to taste. Simmer on low for seven hours, stirring occasionally. During the last two hours of cooking, add in three (or more) cubed potatoes. The potato starch will slightly thicken the stew as it continues to bubble away. When you’re ready to eat, serve the stew with a warm, buttered tortilla and enjoy your bowl of New Mexico comida de alma.

NOTE: This is a recipe that can be adjusted for more or fewer people, so add more chicken, more potatoes, more broth or more green chile as needed.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

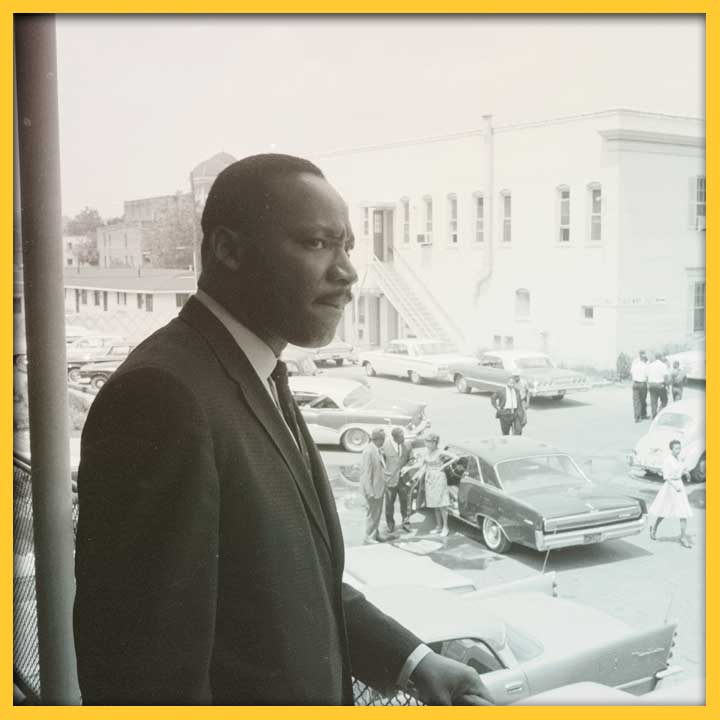

MARTIN L. KING, JR.’S DAMNING LETTER FROM JAIL

By Christopher A. Ulloa Chaves, ED.D.

“In the letter, King used a multi-disciplinary rhetorical approach that applied philosophical, theological, psychological, sociological, political, ethical and economic principles against systemic racism in Alabama…”

SPACESHIPS, RAY GUNS, AND LIFE LESSONS

By Melinda Snodgrass

“science fiction allows you to discuss difficult and fraught topics in what is a safe space and at arm’s length.”

LITERATURE AS GUIDEPOSTS ON MY IMMIGRANT JOURNEY

By Kei Tsuzuki

“What I have learned from books is that there is no one story that explains the world to us or captures our identity entirely. There is power in the specificity of each of our stories…”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

VANESSA BACA

Vanessa Baca is a cook, writer, public relations professional, blogger and podcaster. Her food blog: www.foodinbooks.com, reviews various works of literature and recreates the food references in these books. Her podcast: www.anchor.fm./cookingthebooks, showcases literary cuisine with a variety of guests. She is a native New Mexican, lived briefly in Spain, travels extensively, and has taken cooking lessons in several countries.