UP BY OUR BOOTSTRAPS; TWO LIVES IN RETROSPECT

I found myself fascinated with Dr. McIver’s transition from the stultifying hopelessness of the Segregation Era to the wistful hopefulness of the Civil Rights Era…

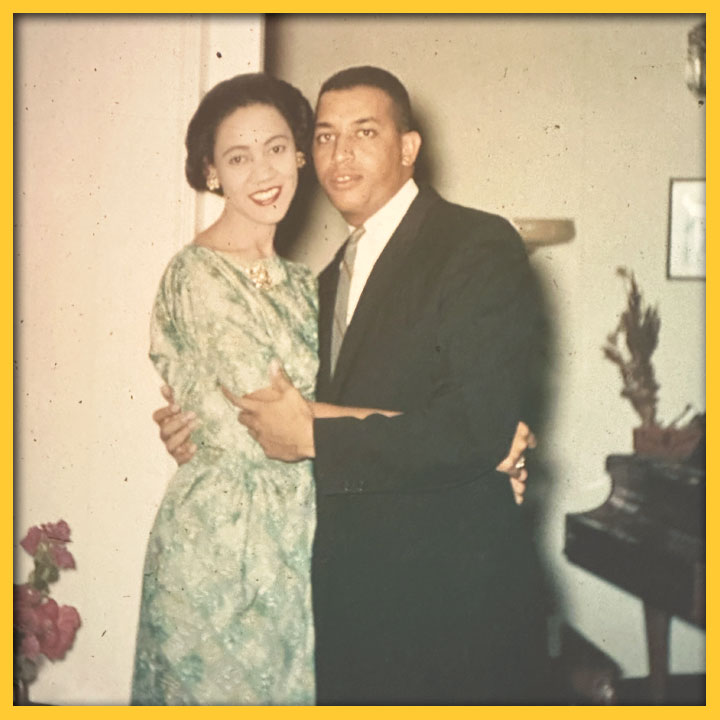

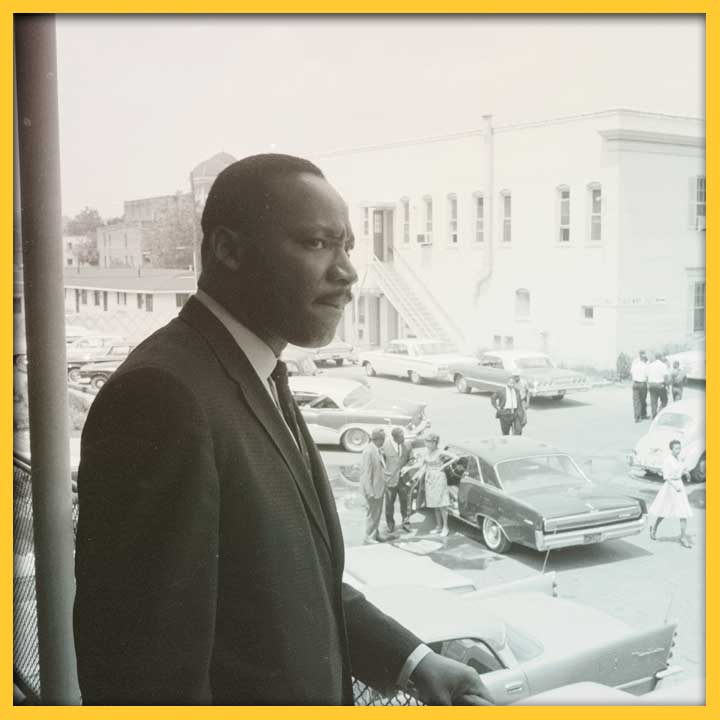

PHOTO CAPTION: Edna and William McIver. Courtesy of William and Edna McIver, private collection.

SHARE:

This article is the first in a series of articles highlighting Albuquerque’s pioneering individuals and families in the African American community. It features conversations with local artist and activist Edna McIver and her life-partner Dr. William McIver. They have led a truly fabulous life together, much of it here in Albuquerque.

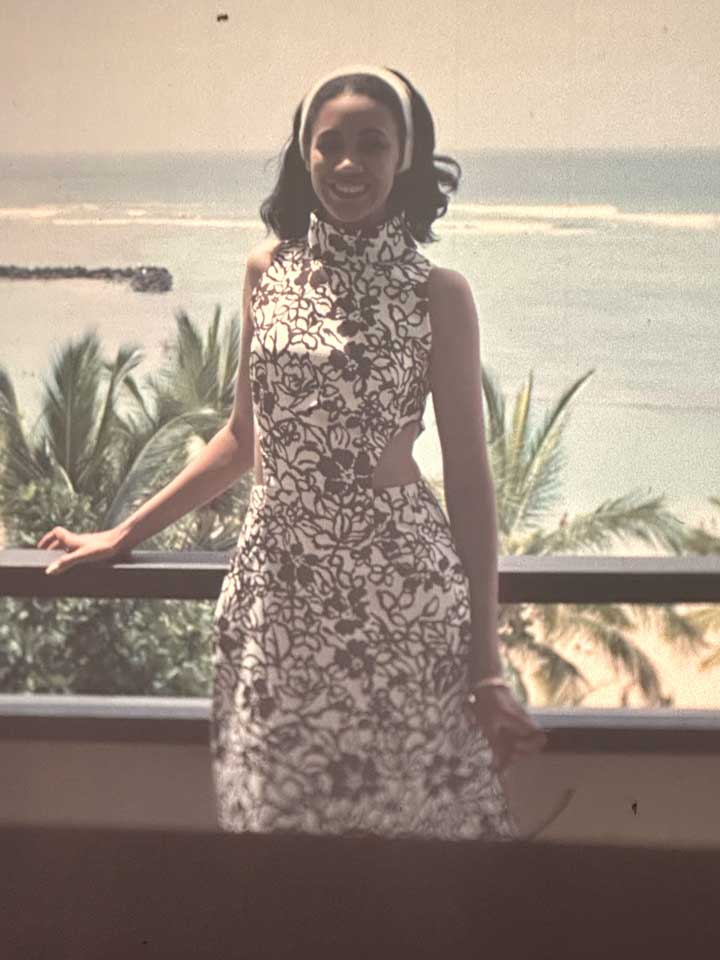

With my knees on a cold tile floor in Veracruz, for a moment, I expected or perhaps wanted to die. Sleep, fever, chills, the room dark, movement to my right … “Here, take these.” I still don’t know what I had contracted or how many patients Dr. William (Bill) McIver had brought back from the brink. Perhaps the first life saved came during his training at Meharry or perhaps at William Beaumont Army Medical Center at Fort Bliss where he met and married a brilliant and stunning schoolteacher, artist, activist. How many more did he save in Vietnam and Germany in the 1960s before settling in as the Chief of Surgery at the top-secret Sandia Army Base in the early 1970s? Fortunately for me, Edna and Bill McIver traveled with the first UNM group to participate in a faculty-led study abroad program highlighting the African Presence in Mexico, summer 2006.

I have been blessed to know the McIver family for nearly 20 years and remain fascinated with the story of William McIver, M.D., F.A.C.S. and Edna “Angi” Nixon McIver. Their 63-year story is of a remarkable journey of an equally yoked African American couple as they navigated Jim Crow, survived the Red Scare, participated in the Civil Rights Movement, lived abroad, landing in Albuquerque where they raised a family of six successful children — Bill Jr., Beth, Stephanie, Angela, Ben and Mike.

When asked about her childhood, Dr. Stephanie McIver, Executive Director for Student Health and Counseling, offered: “Being raised by my parents meant a lifelong exposure to diverse belief systems, global culture and cuisine, respect for all humanity, and a mission to serve people in the broadest way possible. We had a nontraditional upbringing as Black children, starting in the borderlands of Texas with our history of engagement across the border in Mexico, in Germany with the politics and impact of the Vietnam war, then in this uncharacteristic space of New Mexico — raised with my father’s Buddhist philosophy — deep lifelong activism skirting McCarthy blacklisting resulting from my grandparent’s charting of the Southern Conference for Human Welfare (SCHW) brought interesting and diverse people into our childhoods. It was unique, this wide array of people who came in and out of our lives — activists and immigrants who merged action with philosophy. All of us McIvers take that to heart. We were raised in a globally oriented, humanistic family, filled with art and music — with appreciation for scholarship and inquiry.”

I found myself fascinated with Dr. McIver’s transition from the stultifying hopelessness of the Segregation Era to the wistful hopefulness of the Civil Rights Era. From her childhood in segregated El Paso, Edna recalls the colorful hands made of colorful construction paper taped in various windows. Black children were taught not to run to the police, but to run to these homes in case of an emergency. This network of Black families would protect them even if they did not know them. Bill recalled startling differences in social customs that seem senseless today — for example, why Coca-Cola was reserved for White people in Southern restaurants. Committed to maintaining Jim Crow, Robert Woodruff, who led Coca-Cola, resisted integrating marketing efforts or catering to Black consumers. In the 1940s, Pepsi’s Walter S. Mack Jr., recognized the potential of the Black market hiring Hennan Smith, one of the first Black advertising executives, to lead campaigns targeting African Americans.

The McIvers took these things in stride in their youth and never let them dim their overwhelmingly positive outlook on the world. The couple focused on social activism and building a family that reflected positively upon its ability to survive the past and to insulate itself from ongoing cultural, political, or social strife. Ever thoughtful, the couple wrote a book detailing the events of their lives and the historical events and people that shaped them.

Up By Our Invisible Bootstraps: Two Lives in Retrospect, authored by Bill and Edna, captures the history of a family that is quite literally part of American history. The 273-page book traces the family’s and the nation’s melded history from the 1850s to 2023. Chapter One provides a history that includes “The Plight of Indigenous Peoples,” the Buffalo Soldiers, “The Birth of a Nation,” coursing through The Great Depression, and ending with a powerful statement titled “What is Freedom?” The McIvers’ observations seem timeless.

Animosity remains in the milieu and fabric of this great country. It is difficult to understand how we so easily developed amnesia about certain issues and occurrences … the results are ongoing acts of stupidity and hatred, which could be described in no other way but bigotry and racism. Both can easily be camouflaged in institutional racism in education, finance, healthcare, the environment, the penal system, and social interaction, or the lack thereof.

Bill reflects on the family’s Irish and English surnames McIver and Nixon: “The meaning of the name Nixon is ‘undaunted.’” … a fitting name for Dr. Lawrence A. Nixon who took cases to the U.S. Supreme Court for a period of 20-odd years before winning the court cases that allowed Blacks to vote in the White primaries of Texas.

“My Slave Name is Willie” poignantly explores Dr. McIver’s struggles with the racial implications of diminutive naming practices imposed on Black people, a legacy rooted in slavery. This brief but brilliant chapter sets the stage for the astounding genealogy laid out in Chapter Three and myriad stories and anecdotes in the 13 chapters that follow. Stories that range from risky travel at night through the Deep South to conduct medical missions during the time of Schwerner, Cheney and Goodman to reflections on the Orangeburg Massacre, the Black Panther Party, and the devastating story of a horrific crash that killed 10 members of Edna’s family including her sister.

The book contains a section of vignettes from Dr. McIver’s years in medicine — patients with swastikas tattooed on their backs, a woman enduring a breast exam just to see if she could stand being touched by a Black man, and the chilling story of a man choking to death who, with what could easily have been his dying breaths, said to the scalpel-wielding doctor, “Nigger, stay away from me; don’t touch me.”

As in so many other cases, Dr. McIver went on to save the man’s life. More than that, this man became a regular patient. In a way, this story reflects the best characteristics of both Bill and Edna — helping other people despite conditions that suggest doing something else. For all the difficult times they have faced over the decades, the McIvers share story after story of love at first sight, unbound courage, hilarious encounters, and the joys of raising a prosperous family in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Like so many people in Albuquerque, I am happy to be a member of the super-extended McIver family. From Bill I learned how to be the best father that I could be to my own children, and from Edna the ability to see and joyfully appreciate the world through an artist’s eyes. In important ways, they have saved my life more than just that one time that I thought I might die in faraway Mexico.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

RUDOLFO ANAYA: CATCHING CULTURES IN BLESS ME, ULTIMA

By Richard Wayne Etulain

Anaya greatly expands the cultural contributions of his novel by combining the usual (Bildungsroman—growing up theme) with the unusual (complex, diverse New Mexico Hispanic culture)…

UP BY OUR BOOTSTRAPS; TWO LIVES IN RETROSPECT

By Finnie Coleman

I found myself fascinated with Dr. McIver’s transition from the stultifying hopelessness of the Segregation Era to the wistful hopefulness of the Civil Rights Era…

MARTIN L. KING, JR.’S DAMNING LETTER FROM JAIL

By Christopher A. Ulloa Chaves, ED.D.

“In the letter, King used a multi-disciplinary rhetorical approach that applied philosophical, theological, psychological, sociological, political, ethical and economic principles against systemic racism in Alabama…”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

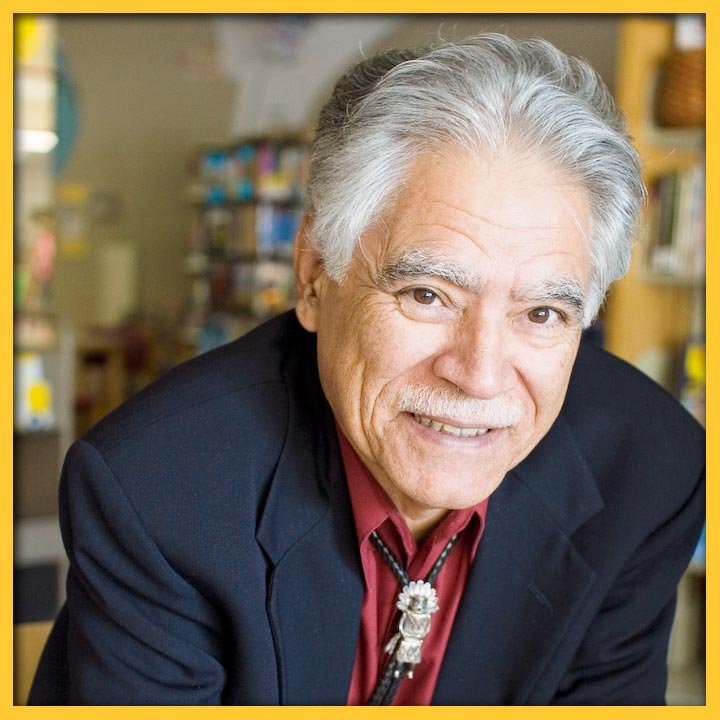

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

DR. FINNIE COLEMAN

Dr. Finnie Coleman is President of the Faculty Senate at the University of New Mexico where he teaches courses in African American literature and culture. An American Council on Education Fellow (ACE), Dr. Coleman has served UNM as Interim Dean of University College, Director of American Literary Studies, and Director of Africana Studies. In the community, Dr. Coleman is a Founding Member and Board Chairman of the ACES Tech Charter School, served for many years on the Governing Board of Amy Biehl High School in Albuquerque, and is Special Advisor to the New Mexico Black History Month Organizing Committee.