WASHINGTON'S FAREWELL ADDRESS: TIMELESS WISDOM

Washington understood the dangers of locating too much political power in too few hands for too long, and in the end refused the temptations of an endless presidency. He opted to make way for someone new.

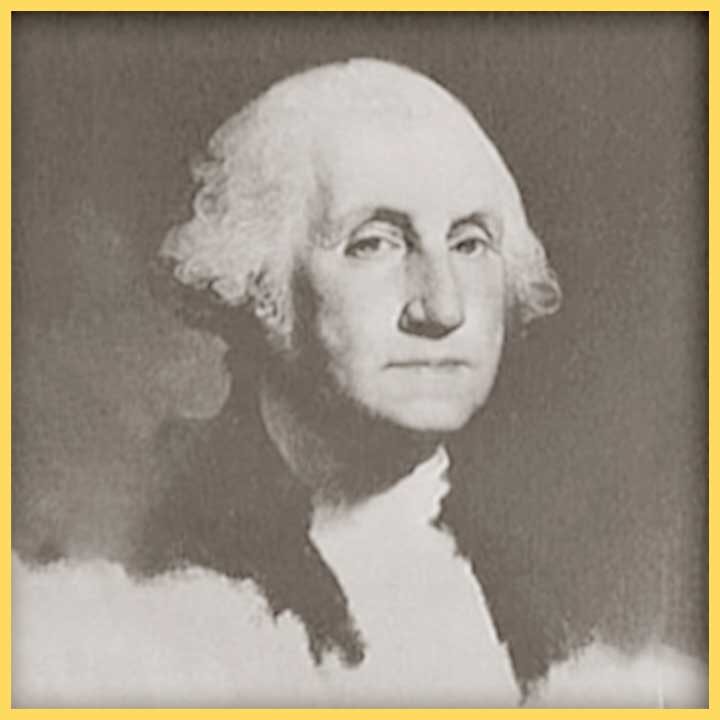

PHOTO CAPTION: George Washington painted by Gilbert Stuart. Credit: Retrieved from the Library of Congress.

SHARE:

In 1796, George Washington found himself contemplating stepping down from the lofty post of President of the United States and retiring from the capital of Philadelphia to Mount Vernon, his bucolic plantation perched above the Potomac River. Legally, the nation’s first chief executive could have campaigned for a third term; it wasn’t until 1951, with the ratification of the 22nd Amendment to the Constitution, after all, that presidents were finally limited to two terms. Thus, many of the President’s political allies hoped he would stay in power indefinitely; John Jay, among others, implored him to run for a third term. “Remain with us at least while the storm lasts,” begged Jay, “and until you can retire like the sun in a calm, unclouded evening.” But Washington understood the dangers of locating too much political power in too few hands for too long, and in the end refused the temptations of an endless presidency. He opted to make way for someone new.

A lesson from Washington’s earlier life illustrates his deep understanding of how unchecked power and privilege can do violence to the fragile nature of liberty and self-government. As commander-in-chief of the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War, he had come face-to-face with forces bent on undermining civilian control of the infant nation he had fought so assiduously to free from British control. In the winter and early spring of 1783, nearly a year and a half after its astounding victory at Yorktown, the Continental Army found itself at odds with the Continental Congress, headquartered in Philadelphia, over a pay shortage. Because Congress did not have the power to tax—under the Articles of Confederation only the individual states held that authority—the national government’s inability to meet its financial obligations to the army was a chronic problem. Soon army officers were circulating inflammatory documents hinting at a military coup, and calling for a mass meeting in the town of Newburgh, New York. Washington immediately outlawed the officers’ meeting, but then called one of his own to be held in the same town four days later. There, he short-circuited the incipient insurrection and called on his fellow officers to oppose any man “who wickedly attempts to open the floodgates of civil discord and deluge our rising empire with blood.” Duly chastened, the officer corps backed down.

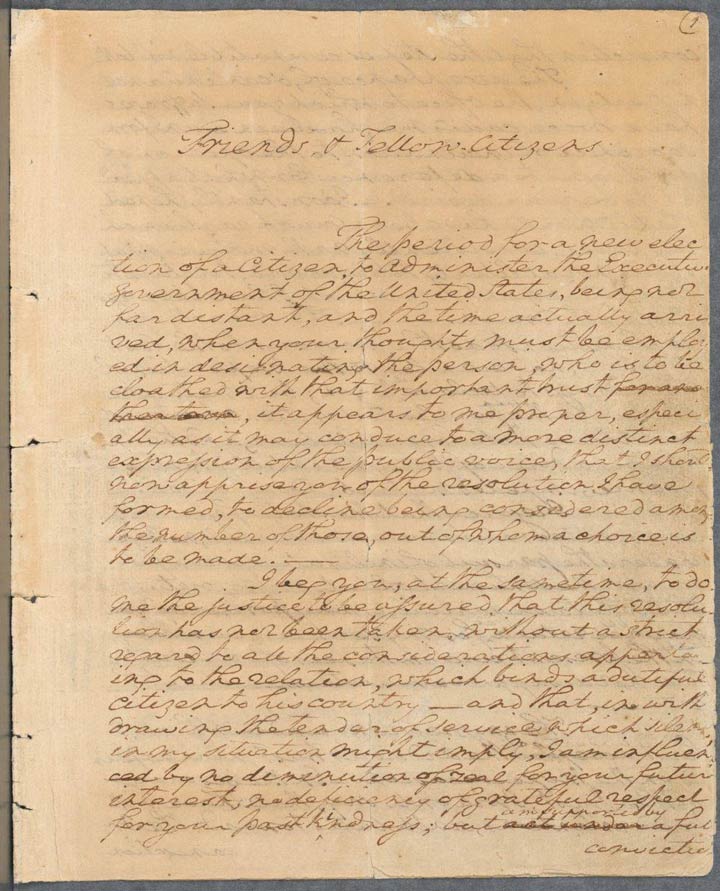

Now 13 years later, with the end of his time as president quickly nearing, Washington wished to bid goodbye to his fellow citizens and pass on to them some of what he had learned about power and politics over his lifetime of service. Calling on Alexander Hamilton to draft, on his behalf and with his input, a farewell address to the country, Washington was planning what was essentially the first notice in American history of a peaceful transition of executive power. “Friends and Fellow Citizens,” the address begins, “the period for a new election of a citizen to administer the executive government of the United States being not far distant, and the time actually arrived when your thoughts must be employed in designating the person who is to be clothed with that important trust, it appears to me proper, especially as it may conduce to a more distinct expression of the public voice, that I should now apprise you of the resolution I have formed, to decline being considered among the number of those out of whom a choice is to be made.” Washington was indeed retiring, and his fellow Americans should be prepared to elect the person best fit “to be clothed with [the] important trust” of the Presidency.

The outgoing President had three main points he wanted to get across in the Farewell Address. His first was that Americans needed to trade their parochial and sectional interests for national harmony and solidarity. “The unity of government which constitutes you one people is also now dear to you,” he reminded his fellow citizens. “It is justly so; for it is a main pillar in the edifice of your real independence, the support of your tranquility at home, your peace abroad, of your safety, of your prosperity, of that very liberty which you so highly prize.” Everything promised to the new nation in the Constitution’s preamble—justice, tranquility, peace, social welfare, and liberty—was ultimately predicated on Americans’ collective willingness to support unity and the goal of consensus. But the former general surely knew there would be those who would try to undermine the principle of union, and he argued that “much pains will be taken, many artifices employed, to weaken in your minds the conviction of this truth.” Citizens would need to “properly estimate the immense value of [their] national Union to [their] collective and individual happiness” and educate themselves so as to avoid being deceived by those who would pull the Union apart. The people of the United States had “in a common cause fought and triumphed together,” Washington argued. But it was only through unified cooperative efforts, namely the “work of joint councils and joint efforts—of common dangers, sufferings, and successes,” that they were ultimately successful in creating a new nation.

Washington’s second argument in his Farewell Address was this: that loyalty to party over nation was dangerous and ultimately destructive. “All obstructions to the execution of the laws, all combinations and associations under whatever plausible character, with the real design to direct, control, counteract, or awe the regular deliberation and action of the constituted authorities, are destructive of this fundamental principle and of fatal tendency,” he declared. These “factions,” as he called them, sought to “put in the place of the delegated will of the nation the will of a party.” Yes, such groups or parties “may now and then answer popular ends,” Washington acquiesced, but “they are likely, in the course of time and things, to become potent engines by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people and to usurp for themselves the reins of government, destroying afterwards the very engines which have lifted them to unjust dominion.” Having cast off the authority of a hereditary monarch in King George III, Americans should be careful not to enable an elected despot, at the head of a popular political party, to take George’s place. The desire to affiliate with one political party or another might be a part of human nature, the retiring president conceded, “having its root in the strongest passions of the human mind,” but the “alternate domination of one faction over another, sharpened by the spirit of revenge natural to party dissension, which in different ages and countries has perpetrated the most horrid enormities, is itself a frightful despotism.” Further, factionalism (or what Washington calls “the spirit of party”) “agitates the community with ill founded jealousies and false alarms, kindles the animosity of one part against another, foments occasionally riot and insurrection.”

Any tendency to put party over country, the president seemed to be saying, would lead to a terrible future for the United States. (This concern over factionalism was something Washington shared with other Founders, particularly James Madison, who blasted the development of factions in representative forms of government in The Federalist Number 10. “The friend of popular governments never finds himself so much alarmed for their character and fate,” wrote Madison, “as when he contemplates their propensity to this dangerous vice” of factionalism.)

Washington’s final broad cautionary point in the address had to do with foreign affairs: avoid entangling foreign alliances. He warned that “against the insidious wiles of foreign influence (I conjure you to believe me, fellow citizens) the jealousy of a free people ought to be constantly awake, since history and experience prove that foreign influence is one of the most baneful foes of republican government.” For Americans, choosing favorites in the game of international relations was ill advised, because ”excessive partiality for one foreign nation” over another would almost certainly mask the true depth of the ally’s influence on the United States and create “the illusion of an imaginary common interest in cases where no real common interest exists.” It would be best, Washington concluded, to “steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world.”

The Farewell Address—with these three themes packed solidly into its more than 7,000-word length—was published September 19, 1796, and began to be picked up by newspapers around the country, just as Washington’s coach departed Philadelphia for Mount Vernon. It would be a mistake not to read the document critically or to think of George Washington (or Alexander Hamilton) as correct on every point made in the address. Similarly, it wouldn’t be fair to assume that Washington’s perspectives on politics and power weren’t somehow colored by his acceptance of chattel slavery. Still, Washington’s Farewell Address proved prescient when it came to imagining the frightening stakes of national disunity. Abraham Lincoln, for one, recognized the wisdom of Washington’s cautious words about sectionalism and factionalism; unfortunately, they proved prophetic when radical sectionalists voted across the American South to secede from the Union, thus sparking the Civil War. There was a reason members of the United States Senate in 1862, as the Civil War was raging, began an annual tradition of reading the text of the address on the floor of their chamber.

The Farewell Address remains relevant today, and is well worth a read. As recent troubling events have shown, factionalist impulses still stalk the land, and insurrection apparently remains for some a viable political tool, despite Washington’s stern warnings. Let this serve as motivation for each of us to get back to the basics of republican citizenship, starting with a review of the address and the other documents that form the basis of the American republic. Then come here to our new blog, Pasa Por Aquí, to ponder and discuss with other readers the meanings of some of the keywords that have come to define our republic, such as “democracy,” “equality,” “freedom,” and “citizenship.” Better yet, consider writing your own post for the blog. Learn more about writing for the blog here.

(The quotes above are drawn directly from the version of the Farewell Address posted at Senate.gov. Other sources consulted include Washington: A Life by Ron Chernow and Washington’s Farewell: The Founding Father’s Warning to Future Generations by John Avlon.)

This post is part of the New Mexico Humanities Council’s Democracy and the Informed Citizen initiative, supported by the Federation of State Humanities Councils and underwritten in part by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

This column was generously funded by a grant from the Mellon Foundation to explore the question of Democracy and the Informed Citizen.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

REFLECTIONS ON THE LOSS OF A NEW MEXICO CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER

By Carlyn N. Pinkins, M. A.

“The Dr. Harold Baileys of the world should inspire us all to do what we can to leave our communities, our towns and cities – our great state – better places than we found them. While we do our part to create the Dr. Harold Baileys of the future, we should also strive to make sure that the Dr. Harold Baileys of our past and present are never forgotten.”

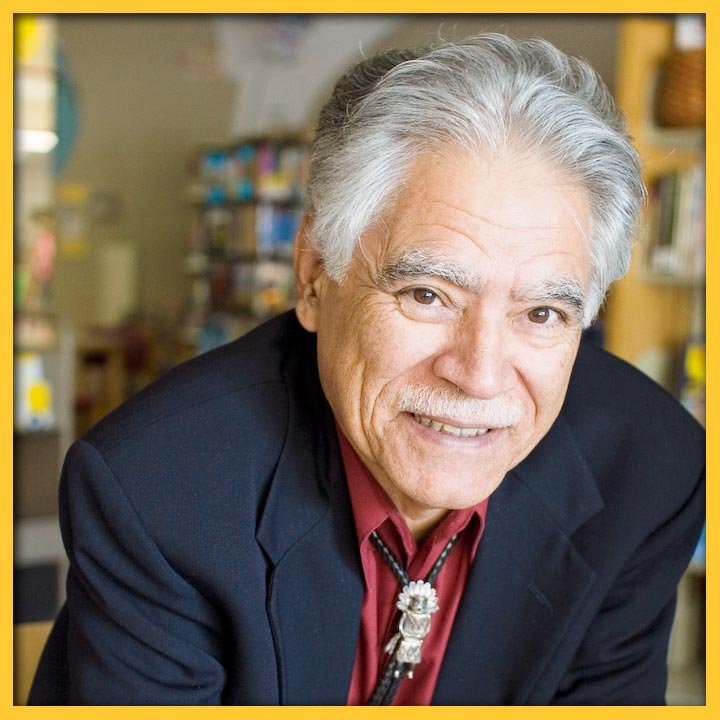

RUDOLFO ANAYA: CATCHING CULTURES IN BLESS ME, ULTIMA

By Richard Wayne Etulain

Anaya greatly expands the cultural contributions of his novel by combining the usual (Bildungsroman—growing up theme) with the unusual (complex, diverse New Mexico Hispanic culture)…

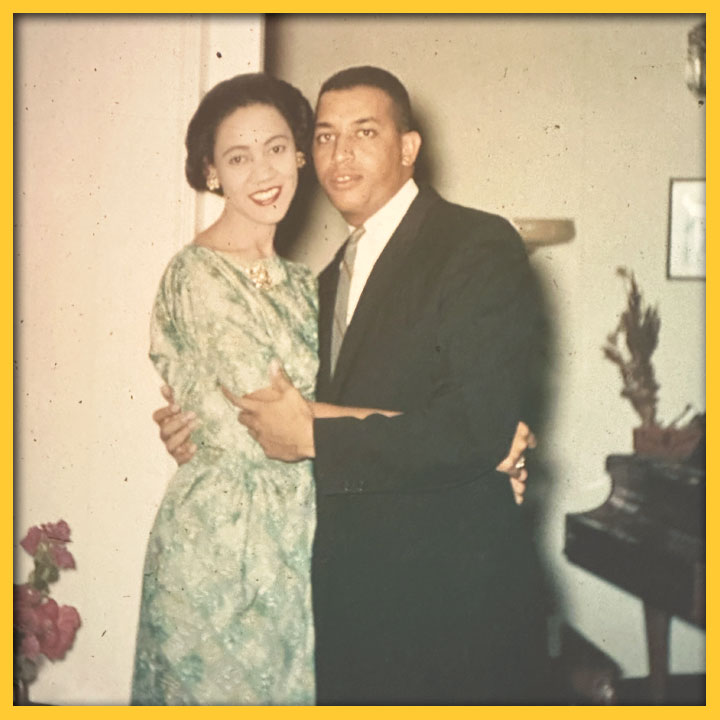

UP BY OUR BOOTSTRAPS; TWO LIVES IN RETROSPECT

By Finnie Coleman

I found myself fascinated with Dr. McIver’s transition from the stultifying hopelessness of the Segregation Era to the wistful hopefulness of the Civil Rights Era…

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

BRANDON JOHNSON

Brandon Johnson, a native of Utah, comes to NMHC from the National Endowment for the Humanities where he served as Senior Program Officer in the Office of Challenge Grants.