SHARE:

“My grandpa was a savage before savage was in style.”

-Snotty Nose Rez Kids, “Savages”

I have been hearing the word savage more than I would like to acknowledge. I have noticed that the nonchalant use of the word ‘savage’ is circulating more frequently into conversations. My understanding is that most people are unaware of the historical, social, political, mental and emotional baggage that the word carries, especially to Indigenous peoples. I ask: Why might Indigenous peoples cringe when they hear the word savage used in a casual conversation? Why might describing someone’s actions as ‘savage’ make an Indigenous person flinch? Why might the word make us uncomfortable, or worse, saddened? I write this essay from the scholarly perspective of an Indigenous woman. While my account is not all-inclusive, I hope that I can provide a nuanced understanding of the word’s use.

According to Hensleigh Wedgwood in 1872, savage draws from the French word, sauvage; Italian, selvatico, selvaggio, salvaggio; and Latin, sylvaticus — in which the words convey the idea of “savage, wild, untamed, forest-bred.” In the Oxford Dictionary savage is defined as “in a state of nature,” “of wild or unrestrained behaviour,” “uncivilized,” “furiously angry,” and “woodland-, wild, … wood, [and] forest.” In both Wedgwood and the Oxford Dictionary, the word savage draws from the Latin word, silva or sylva, meaning “of the woods” or “inhabitant of the woods.”

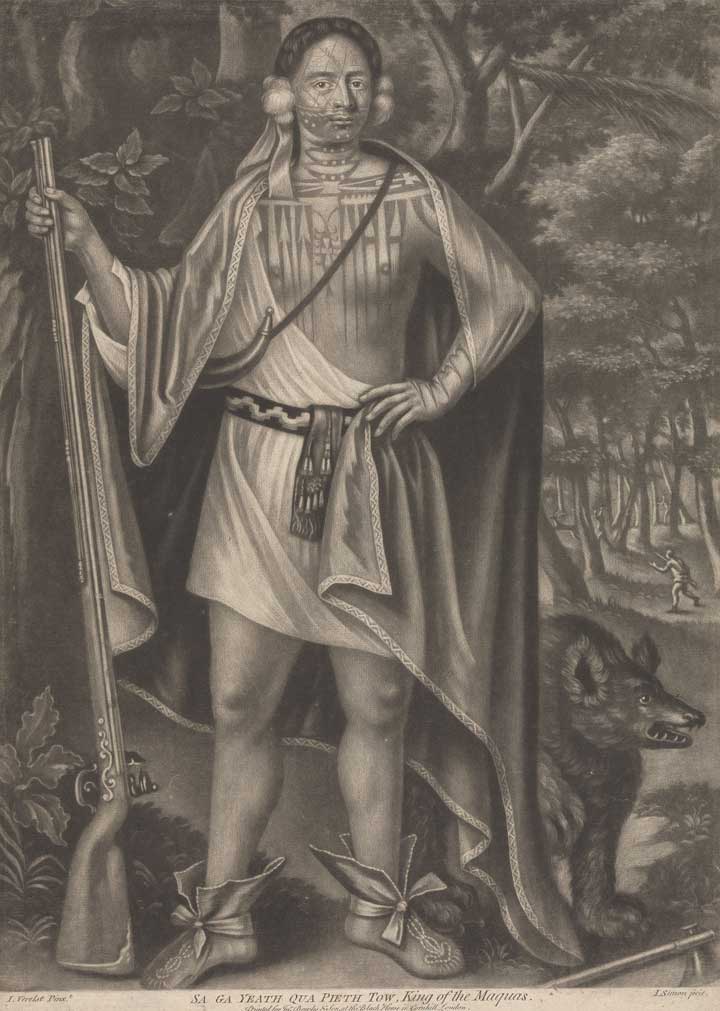

How might the correlation between nature and the woods be offensive to Indigenous peoples? How might we begin to understand the word savage as denigrating? Beyond the stereotypical image of the Noble Savage (Figure 1) — an Indigenous person living in pure harmony with nature uncorrupted by civilization — let us consider the context from which the association of nature emerges. I would like to start with the idea of the sublime. While contemporary use of the word sublime asserts nature as awe-inspiring and beautiful, in the traditional sense, the sublime is a response to nature — nature that is horrifying and involves all the senses in pure terror. As philosophized by Edmund Burke in 1757, the sublime in nature arouses the feeling of astonishment, in which the mind is suspended to a degree of horror. In so suspending the mind, Burke turns to the power of fear, stating that, “whatever therefore is terrible, with regard to sight, is sublime, too.”[1] In Burke’s philosophy of the sublime, he readily identifies that the ruling principle of the sublime is terror, whereby reverence, fear, wonder and respect take root. By positing the sublime as a response to nature, nature was thus terrifying.

With this in mind, might we begin to imagine how Indigenous peoples’ associations with nature would transform us into something frightful, a savage? In William Cronon’s seminal essay, “The Trouble with Wilderness or Getting Back to the Wrong Nature,” he asserts that the connotation of nature and wilderness is a mirror of human society’s longings and desires. He states, “As late as the eighteenth century… [to] be a wilderness then was to be ‘deserted,’ ‘savage,’ ‘barren’ — in short, a ‘waste,’ the word’s nearest synonym. Its connotations were anything but positive, and the emotion one was most likely to feel in its presence was ‘bewilderment’ or ‘terror.’[2] While we — contemporary peoples — might consider the association of nature as benevolent or, at the very least, positive, the context from which the association arises is quite the opposite for Indigenous peoples. As Patrick Wolfe has stated, “So far as Indigenous peoples are concerned, where they are is who they are …” [3]. To be associated with the wilderness implied a threat to mankind and civilization.

In 1889, Theodore Roosevelt, in his book “The Winning of the West,” asserts that white people are the “representatives of civilization,” in which,

“All men of sane and wholesome thought must dismiss with impatient contempt the plea that these continents should be reserved for the use of scattered savage tribes, whose life was but a few degrees less meaningless, squalid, and ferocious than that of the wild beasts with whom they held joint ownership.”[4]

The use of ‘scattered savage tribes’ signals that Indigenous peoples are strongly associated with nature as inhabitants of the woods. Most explicitly, the word savage is synonymous with Indigenous people. In being scattered, Indigenous peoples lack a complex social structure and civilization. As Veronica Yellowhair (Diné) states in her article, “The End of ‘Savage,’” the word savage implies untamed animals. Yet, Roosevelt directly asserts that Indigenous peoples are dirty, vicious and inferior to animals. He thus advocates for the genocidal removal of Indigenous peoples from our respective lands: “It is of incalculable importance that America, Australia, and Siberia should pass out of the hands of their red, black, and yellow aboriginal owners, and become the heritage of the dominant world races.” [5] Through a settler colonial American context, obtaining the land from Indigenous peoples, through wars and treaties, was “for the benefit of civilization and in the interests of mankind.”[6] Savages do not belong in civilization; we are its antithesis.

The question is, why does any of this matter when we use the word today? When we continue to ignore how the dehumanization of Native people was and is exacerbated by the word savage, we perpetuate negative stereotypes of Native peoples, such as the war-mongering headdress-wearing Indian chief. We continue to legitimize the use of a word that is and was used as a racial slur against Indigenous and Black peoples, and I can only speak to the Indigenous experience. Lastly, we signal to Indigenous youth that a mindset of superiority over Indigenous peoples continues to persist.

Notes

[1] Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Inquiry Into the Origin of Our Idea of the Sublime and Beautiful, edited by Adam Phillips (Oxford University Press, 1990), 53.

[2] William Cronon, “The Trouble with Wilderness: Or Getting Back to the Wrong Nature,” Environmental History, 1, no. 1 (1996): 8.

[3] Patrick Wolfe, “Settler Colonialism and the elimination of the native,” Journal of Genocide Research 8, no. 4 (2006): 388, emphasis original.

[4] Theodore Roosevelt, The Winning of the West, Volume 3 (New York: The Review of Reviews Company, 1910), 129.

[5] Roosevelt, The Winning of the West, 130.

[6] Roosevelt, The Winning of the West, 128.

Bibliography

Burke, Edmund. A Philosophical Inquiry Into the Origin of Our Idea of the Sublime and Beautiful, edited by Adam Phillips. Oxford University Press, 1990.

Cronon, William. “The Trouble with Wilderness: Or Getting Back to the Wrong Nature.” Environmental History, 1, no. 1 (1996): 7-28.

Metz, Darren and Quinton Nyce. “Savages.” The Average Savage. Ingrooves Music Publishing LLC, 2017.

Oxford English Dictionary. “Savage.” Accessed November 15, 2022.

Roosevelt, Theodore. The Winning of the West, Volume 3. New York: The Review of Reviews Company, 1910.

Wedgwood, Hensleigh. A Dictionary of English Etymology, second edition. London: Trubner & Co., 1872.

Wolfe, Patrick. “Settler Colonialism and the elimination of the native.” Journal of Genocide Research 8, no. 4 (2006): 387-409.

Yellowhair, Veronica. “The End of ‘Savage’.” Writing for Change Journal (blog). 2022.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

CULTURE ALSO COMES IN THROUGH THE KITCHEN

By Teresa Dovalpage

“Here in Hobbs, where I currently live, the Cuban community, very small when we moved here seven years ago, is growing fast.”

RUDOLFO ANAYA’S MAGIC WITH WORDS

By Chris Chaves

“It seems that, for Anaya at least, libraries and the magical words hidden in their books can serve to impart knowledge, facilitate love, and encourage empathy about others.”

ECOLINGUISTICS AND HOW LANGUAGE CAN SAVE THE WORLD

By Monika Dziamka

“It’s hard to talk about gender, equality, and equity without also talking about issues surrounding sustainability and the environment—which in turn relate to issues of power, colonialism, and capitalism.”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

FELICIA BARTLEY

Felicia Bartley is from the Pueblo of Isleta. She received her master’s degree in Public Humanities from Brown University.