SHARE:

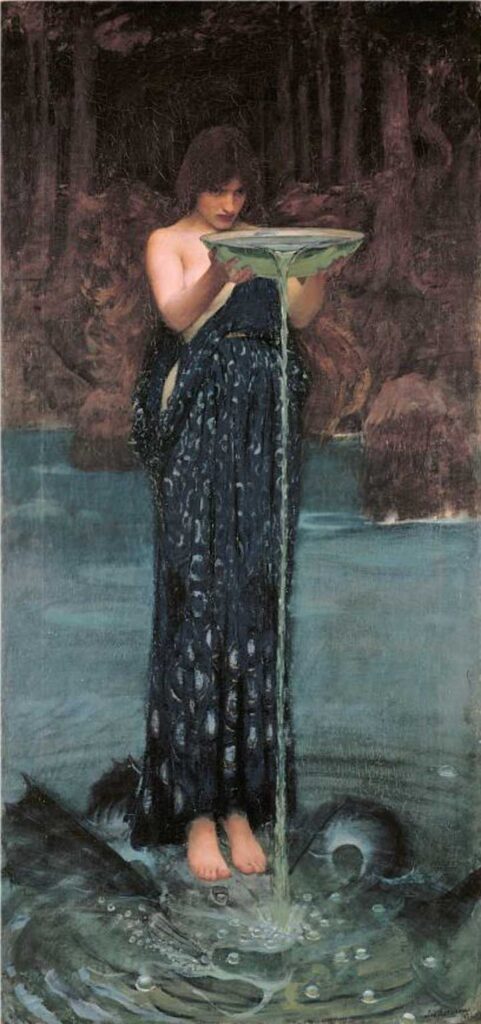

Until quite recently, the archetype of the Witch in Western culture has been the primary representation of the monstrous feminine. However, in the last century this archetype has been transformed from purely monstrous to also being a representation of feminine power. In fact, the characteristics that once made the Witch monstrous —independent, openly sexual, non-conforming — are the characteristics that make her powerful. The key to the transformation lies in how the perception of those characteristics has changed.

The bulk of European witch hunts and executions occurred from the 1400s into the mid-1700s. Seventy-five to 85 percent of those officially accused and executed for witchcraft were women. Yes, anyone could be a witch, but it was clear to the Church that women were far more likely to be witches. In the Medieval period, Church dogma stated that because Eve had been created from Adam’s rib rather than the clay God used to create Adam, they were made from inferior material and would always be weaker than men in all ways. Their intrinsic inferiority made them more prone to sin of all kinds, including witchcraft. This attitude survived well beyond the Medieval period.

It’s important to note that practicing magic was not considered the same as being a witch. Magic was accepted as real and was generally considered a good thing. Magic practitioners — often referred to as “cunning folk” — played important roles in their communities as healers and sources of wisdom and used their magic to help their communities. A witch, on the other hand, used magic to harm their communities under the direction of the Devil in exchange for something they desired (money, power, etc.). Witches turned their backs on God to serve the Devil, which made witchcraft the ultimate heresy, and heresy of all kinds was punishable by death.

Obviously, no one was literally selling their soul to the Devil. So, in nonmagical terms, what was a witch? A witch could be anyone who did not accept or properly conform to their role in society and thus threatened the status quo. For women, that role was wife and mother. Single women over the age of 30, divorcées, and widows were most likely to be accused simply because they did not fulfill these roles properly. “Wife and mother” encompassed many tasks such as caring for children, assisting in delivering babies, helping to plant and harvest crops, and warming their husband’s bed. When a woman was accused of witchcraft, sick children, blighted crops, and even a man having saucy dreams and thoughts about her could be used as evidence of her crime.

Take Bridget Bishop for example. Bridget was the first woman executed in the Salem Witch Trials. The only physical evidence of her supposed crime was her red bodice. There were strict rules in Puritan colonies that limited acceptable colors for clothing, and red — a color associated with lust — was definitely not on the list. So, not only did Bridget choose an unacceptable color for her new bodice, she chose a sexually suggestive color. A harlot, perhaps, but a witch? Not long after she began wearing it, a man named William Stacy accused her of visiting him in spirit form dressed in her sexy red bodice and tempting him to commit fornication. The combination of her refusal to conform to the rules and William Stacy’s dream about her was what put the noose around her neck.

So how did the archetype of the Witch transform from being pure evil to empowering? Part of the answer lies in non-conformity being seen as a sign of witchcraft. Deviating from social norms and roles has always been seen as both dangerous and exciting. In times of rapid social change, it can be seen as revolutionary. Fast forward from the American Revolution, through the Civil War and Reconstruction era (both of which saw increased numbers of people practicing alternative spiritualities) and stop at the birth of Second Wave feminism in the early 1960s.

Second Wave feminism expanded the discussion of women’s rights beyond suffrage to include reproductive rights, workplace rights, and fueled changes to divorce and custody laws so that women could more easily escape abuse. The rise of Second Wave feminism in the U.S. coincided with the Vietnam War protests, the Civil Rights Movement, and an increased popularity of alternative spiritualities, as seen in previous centuries. Many people — especially women — were flocking to goddess religions, such as Wicca. Magic-based spiritual practices at this time were heavily influenced by Second Wave feminism. Many women intertwined their spiritual growth with their political/social struggle and believed that doing so was necessary to achieve the cultural changes they wanted to see.

The spike in numbers of magic-based spiritual practitioners in the 1960s was accompanied by increased visibility of witches in music and visual media. Although witches were featured characters in music such as Berlioz’s 1830 Symphonie fantastique’s fifth movement (“Dream of the Night of the Sabbath”), it wasn’t until the late 1960s and early 1970s that witches came to represent more than danger. Songs such as Fleetwood Mac’s “Rhiannon” and the Eagle’s “Witchy Woman” tell the story of witches who are powerful, mysterious, and unattainable targets of desire. Other artists at this time used music to highlight their own magical practices. Jinx Dawson, a self-proclaimed witch and lead singer of the band Coven, wanted to use music to educate the public about witchcraft. The band’s debut album—titled “Witchcraft Destroys Minds and Reaps Souls” — achieves this by using rock-and-roll to give a lecture on folklore. It also leans into the worst stereotypes of witches by including the recitation of a Satanic Mass as if to say “I’ll show you how bad we can be.” This attitude speaks to the struggle of finding your place in a world that would rather deny agency and force conformity than allow any deviation from social norms.

Some current artists, such as Princess Nokia and Ghanaian artist Azizaa Mystic, bring this desire to educate to their music as well. Princess Nokia’s song “Brujas” discusses her ethnic and magical genealogy which includes Nigerian, Puerto Rican, Arawak, and Yoruba. Yoruba doubles as her inherited practice as it is a West African tribe, language, and magic-based spiritual practice. Azizaa Mystic’s entire discography focuses on educating the public about her Voodoo practice. Her music accomplishes this by celebrating transgressive women and condemning the destructive way Christianity was spread through Ghana, and is beautifully highlighted in her song and music video “Black Magic Woman.” Both songs tell the listener a story of oppression and reclamation of power.

Visual media also played an important role in the Witch’s transformation. Once again, the 1960s mark the turning point of how witches were depicted in television and films. One of the most recognizable portrayals of a “good witch” from this time is Samantha from the series Bewitched. Samantha fills the traditional feminine roles of wife and mother as well as being a witch. She uses her powers to solve many of her family’s problems, even though her husband expressly forbids her to use magic. She represents the possibility of being a good wife and mother while maintaining her independence. Samantha shows the public that the Witch can exist as something other than the monstrous feminine. Positive portrayals of witches in visual media continued to increase through the decades, and even helped increase the number of Wiccans and other types of witches. The more witches were portrayed as successful members of society who still maintained their power, the more young audiences identified with those characters and wanted to emulate them in real life. While some viewers may have started practicing magic just for fun, many stuck with it and found empowerment and community.

These examples are a small fraction of the ways the archetype of the Witch has been transformed through popular culture. During the last several centuries of systemic oppression, women refusing to accept or be limited by their designated social roles was and continues to be revolutionary. Like the Witch, many of us hunger for the power and freedom that is beyond what society tells us we should have. We are dangerous because we know we deserve more.

© Keelyn Byram, 2023

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

NEW MEXICO’S AMAZING BLACK HISTORY

By Rob Martinez, State Historian of New Mexico.

“African history runs deep in New Mexico. Black history is often framed within the institution of slavery, but in New Mexico, New Mexicans of African descent were ambassadors, explorers, colonists, soldiers, cowboys, discoverers, settlers, businessmen, educators, and much more.”

SCANNING FOR STORIES

It was a Friday afternoon in November and I was driving on a state road through the hills of the Mimbres Valley. The entire landscape was bathed in a golden hue because the tree leaves had made their full conversion to a bright yellow color just before falling off the branches.

REFLECTIONS ON THE LOSS OF A NEW MEXICO CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER

By Carlyn N. Pinkins, M. A.

“The Dr. Harold Baileys of the world should inspire us all to do what we can to leave our communities, our towns and cities – our great state – better places than we found them. While we do our part to create the Dr. Harold Baileys of the future, we should also strive to make sure that the Dr. Harold Baileys of our past and present are never forgotten.”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

KEELYN BYRAM

Keelyn holds a BA in Anthropology and an MA in American Studies, both from the University of Wyoming. Her thesis research centered on modern witchcraft and explored topics such as the commodification of spirituality and how magic-based spiritual practice mirrors Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction techniques. Her thesis, Witchcraft and Wholeness: Twenty-First Century Magic, is available through ProQuest. Keelyn currently works for the New Mexico Humanities Council as the Grants Manager and Speakers Bureau Manager.