SHARE:

Winter nights and cold weather invite more opportunities to stay at home, something I look forward to every year. As a native New Mexican, I love the sun and need our strong, dry heat to sink deeply into my bones. But when the days grow shorter, I welcome the cold and dark as a time to read, watch and listen to scary things. It’s a time for fearful fun, for reconnecting with the monsters and ghosts of old and new. To me, Halloween is just the start of spooky season.

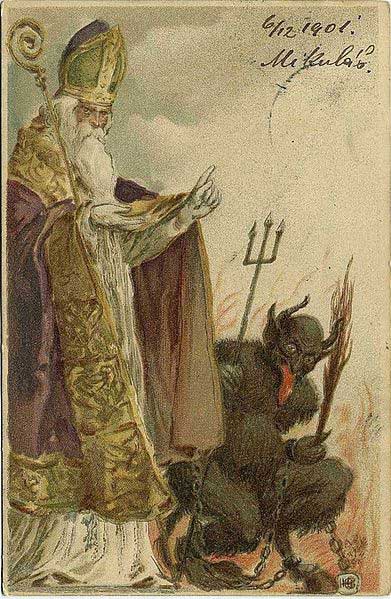

Perhaps it’s my Polish side that hungers for a side of horror during the holidays. My parents, who are from Poland and moved to Albuquerque in 1981, four years before I was born, told me stories of Krampus as I grew up. On St. Nicholas Day, which occurs on Dec. 6, I’d wake with trepidation to see if St. Nicholas — aka Santa — had left me a present or a warning. If I’d been good, I’d find a little brown paper bag filled with oranges, apples, nuts and chocolate. I was only ever good (naturally!), but had I been bad, I would have received a stick or a rock or a lump of coal. The present indicated that I should keep up the good work, to be rewarded with even more presents at Christmas. The warning, however, sent a clear message: Shape up, or Krampus will get you.

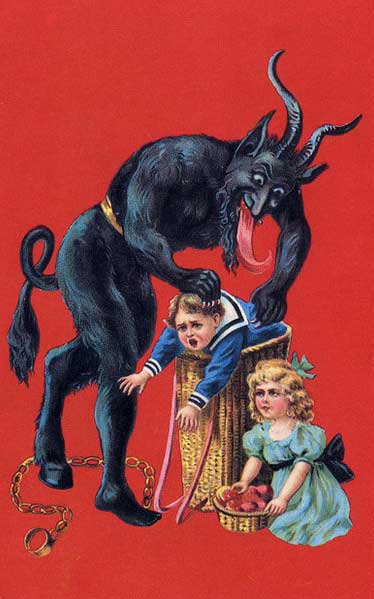

Who (or what) is Krampus? He’s Santa’s sidekick, of course — a tall, horned beast with large, yellow eyes and sharp teeth, a demon-like entity with hoofed feet, thick black fur and a long red tongue. Come Christmas, you’d revel in all the pleasant sensory delights of the day — or you’d smell Krampus’s foul breath upon your face, feel the sharpness of his long nails as he closed his claws around your arms and snatched you away into the darkness, into the giant bag or basket he carries only for naughty children. You’d be kidnapped, and before you’d disappear forever, Krampus would use that very stick or rock or whatever you received as a warning, adding his own weaponry, alternating between beating you and tickling you with that hideous serpentine tongue.

Nice, right? Krampus is the spice to Santa’s sugar. Neither one is as good alone as they are when paired with the other.

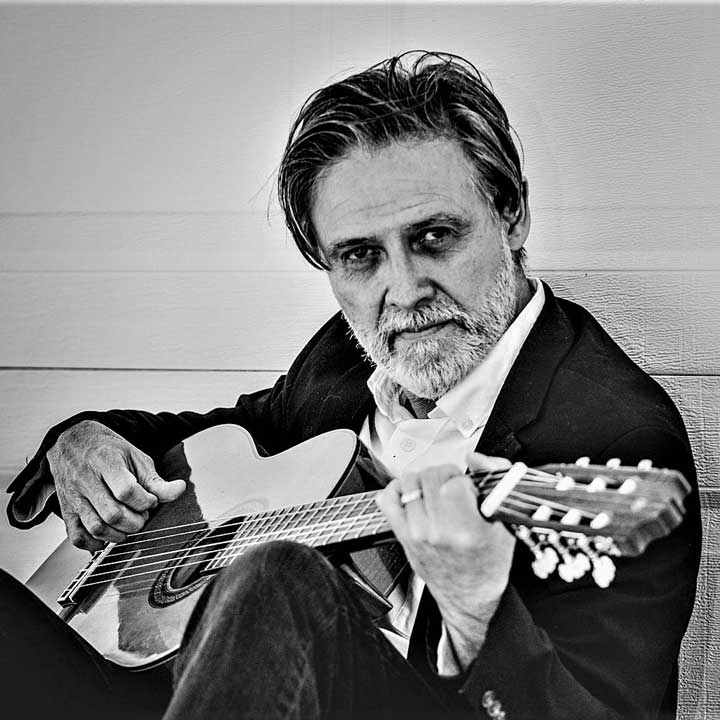

In his recently published book The Fright Before Christmas: Surviving Krampus and Other Yuletide Monsters, Witches, and Ghosts, author Jeff Belanger writes:

…Halloween is just the warm-up act for the most frightening holiday of the year. Most of us know this holiday as Christmas, but it had gone by other names long before it became associated with Christians. Saturnalia. Yule. Midwinter. No matter what label you prefer, all of this fuss centers on a cosmic event that’s occurred annually for billions of years no matter what you believe (or don’t believe): the Winter Solstice. …You look out your window at the landscape and see that winter kills everything. The grass. The trees. The flowers. Even the ponds and lakes are frozen in eerie stillness. It’s bleak and desolate. Get caught outside unprepared, and the winter will kill you too.

The Winter Solstice is a time for fear. And in the darkest corners of that fear…there be monsters lurking![1]

That’s right — Krampus is but one of many wintertime monsters. There’s Karakoncolos, a Bigfoot-type being who likes to get into people’s homes to cause mayhem and can shape-shift. He can look like anyone, even your relatives. There’s Père Fouettard, a butcher who carries out the orders of his boss Santa Claus, punishing bad children through beatings or worse. There’s Gryla, a witchy ogress who enjoys cooking people into stews. Her deadly pet, the Yule Cat, also has a taste for human flesh.

I wasn’t raised with stories of the Yule Cat, Christmas Bigfoot or Santa’s butcher, but Polish folklore is full of other monsters, monsters that are available year-round —such as Baba Yaga, a witch who lives in a magical house that sits upon giant chicken’s legs. My parents had a wooden carving of Baba Yaga in our dining room, which I find to be an appropriate place since she likes to eat children. Some of these monsters, including Baba Yaga, have become more known around the world in recent years thanks to the popular book series The Witcher, written by Polish author Andrzej Sapkowski. These books are the basis of the video games of the same name, as well as the TV series on Netflix starring Henry Cavill. During my last visit to Poland, I found volumes one and two of Bestiariusz Słowiański, or Slavonic Bestiary, by Paweł Zych and Witold Vargas, a richly illustrated series that catalogs hundreds of creepy creatures. Topielica is one of them, a demon in the form of a beautiful blonde woman who appears in bodies of water when the moon is bright, particularly during cold months. She casts her long, shimmering hair on the water’s surface, and each strand of hair emits some spellbinding sound, together creating an exquisite melody that lures people to her so she can drown them. Kaduk is another one, a reptilian monster with a gigantic mouth full of fangs that can eat an adult human being whole.

As the days grow shorter, I like to bring out these two volumes to add to my displayed stacks of Alfred Hitchcock anthologies, Edith Wharton ghost stories and contemporary horror novels. I enjoy curling up with a hot beverage and spending time with these old friends, fanged and hoofed and magnificent and terrifying as they are. When my 4-year-old daughter gets a bit older, I’ll share them with her, but she already knows about Krampus, just as I did at her age. And as apprehensive as she is of him sometimes, asking again whether she’ll get a gift or a warning on St. Nicholas Day, she also seems to like him a little bit, or maybe she appreciates what he can do.

My daughter has a friend who sometimes scratches and hits her when he doesn’t get his way during their playtime at school. This behavior used to be more frequent; he now seems to be better at expressing his anger or frustration in safer, more appropriate ways, and they generally play well together. Still, he occasionally behaves in a way I would describe as “badly.” Recently, after he got in trouble with their teacher, my daughter smiled conspiratorially and said to me, “Mama, he doesn’t know about Krampus. He better watch out. Krampus is coming!”

My daughter’s remark made me laugh, and I told her she should tell her friend about Krampus.

“Don’t forget to mention the long red tongue,” I added.

She also knows about La Llorona, so I said she could tell him about her too, for good measure. She giggled and said, “Oooo yeah!”

If this little boy refrains from scratching and hitting her and anyone else as a result of suffering through a nightmare or two, I think that’s a reasonable exchange. I hope the fear of getting taken away by Krampus ultimately gets replaced by some more profound, more meaningful incentive—for him, for her, for Krampus-fearing children everywhere. Since that exchange, however, I’ve been thinking about what makes (some) fear so fun, why I enjoy horror so much during these darker months, and how we make up scary stories to help make sense of the world.

“Fear creates distraction, which can be a positive experience. When something scary happens, in that moment, we are on high alert and not preoccupied with other things that might be on our mind (getting in trouble at work, worrying about a big test the next day), which brings us to the here and now,” write professors Arash Javanbakht and Linda Saab. “When we overcome the initial ‘fight or flight’ rush, we are often left feeling satisfied, reassured of our safety and more confident in our ability to confront the things that initially scared us.”[2]

In a 2022 study from the Recreational Fear Lab at Aarhus University in Denmark, researchers found that “One explanation for why people engage in frightening fictional experiences is that these experiences can act as simulations of actual experiences from which individuals can gather information and model possible worlds. …Simulation is useful because it can substantially reduce the cost of exploring, experiencing, and learning about some phenomenon, particularly if that phenomenon is dangerous.”[3]

As an example, the researchers point to the popularity surge of the movie Contagion in the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic. But of course, unfortunately, there are many things in our modern world in addition to a global pandemic that are truly horrifying — very real things to be afraid of, and for good reason. Indeed, we can take our pick from a vast and plentiful spectrum that exists out there, at this very moment: a poisonous spider, contaminated water, a car accident, affording health care, actual human kidnapping, murder, war, genocide, nuclear weapons, on and on.

My daughter asked me whether Krampus comes for bad adults too. I told her, no, because that’s where the police and other “security people” come in, suddenly struggling to explain in simple terms what the criminal justice system is. My mind flashed to war crimes and weapons deals and repeat offenders and the MMIW[4] crisis and finally I said, “Maybe Krampus should come for bad adults too.”

As I consider how to add Krampus to my Christmas decorations this year, and as I read more about fear itself, I understand that I seek out scary stories to feel afraid so I can confront fear and overcome it — to test my limits and, ultimately, to feel more assured of my own courage and fortitude. Perhaps I think of my Polish ancestors in ways I don’t fully realize and I scare myself so that, in some silly way, I can tell myself that I, like them, could withstand the historic terrors they survived. I tell my daughter about Krampus, Baba Yaga, and La Llorona so she can be braver and stronger as well— to be like our ancestors, but also to be brave and strong in our own ways. I want her to feel fear in these playful ways in order to be better able to overcome fear in the real world. Fear can be useful. Fear can be empowering. In fear, there are many lessons—many gifts—for us all. And it just wouldn’t be the holiday season without at least one gift.

[2] PBS: “The science of fright: Why we love to be scared“

[3] National Library of Medicine: “Pandemic practice: Horror fans and morbidly curious individuals are more psychologically resilient during the COVID-19 pandemic“

[4] US Department of the Interior Indian Affairs: “Missing and Murdered Indigenous People Crisis“

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

NEW MEXICO’S AMAZING BLACK HISTORY

By Rob Martinez, State Historian of New Mexico.

“African history runs deep in New Mexico. Black history is often framed within the institution of slavery, but in New Mexico, New Mexicans of African descent were ambassadors, explorers, colonists, soldiers, cowboys, discoverers, settlers, businessmen, educators, and much more.”

SCANNING FOR STORIES

It was a Friday afternoon in November and I was driving on a state road through the hills of the Mimbres Valley. The entire landscape was bathed in a golden hue because the tree leaves had made their full conversion to a bright yellow color just before falling off the branches.

REFLECTIONS ON THE LOSS OF A NEW MEXICO CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER

By Carlyn N. Pinkins, M. A.

“The Dr. Harold Baileys of the world should inspire us all to do what we can to leave our communities, our towns and cities – our great state – better places than we found them. While we do our part to create the Dr. Harold Baileys of the future, we should also strive to make sure that the Dr. Harold Baileys of our past and present are never forgotten.”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

MONIKA DZIAMKA

Monika Dziamka is a writer and editor from Albuquerque. She has an MFA in creative writing from Queens University of Charlotte, a Master's in publishing from Columbia, and a BA in journalism from UNM. As an editor, she has helped hundreds of authors publish their novels, memoirs, mysteries, academic textbooks, and more. Her own creative writing has appeared in New Mexico Magazine, the Chicago Review of Books, River Teeth, and elsewhere. Monika is a mentor in the UNM Student Publications alumni program and a volunteer with the Read to Me! ABQ Network, which promotes early childhood literacy and distributes gently used books to kids around Albuquerque and Bernalillo County. Read banned books, support local bookstores, and connect with Monika through www.monikadziamka.com.