A SOLDIER'S PASSAGE: A NEW MEXICO-MADE FILM EXPLORES THE ART OF SAYING "GOODBYE" TO DAD

- By Paul Ingles

- No Comments

“I told my therapist, ‘Seeing my father take his last breath was probably the most profound thing I’ve ever witnessed. I keep playing it over and over in my head. And you know what? I don’t think I WANT to forget it.’ ‘You never will,’ he said assuredly.”

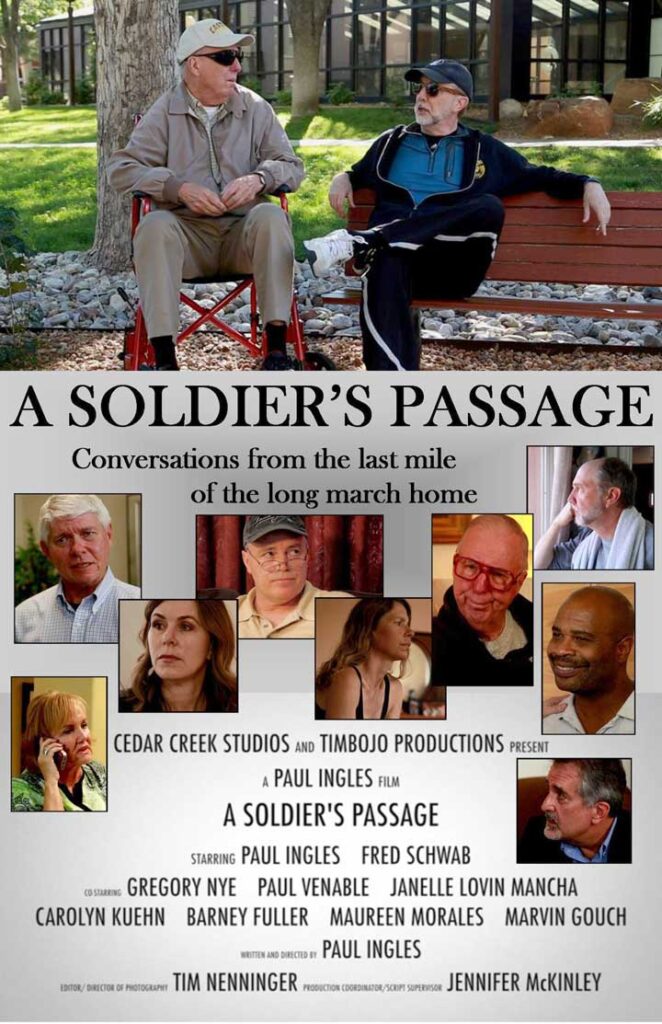

IMAGE: Paul Ingles with his father John, in 2014.

SHARE:

Dec. 5, 2004, I was standing in the wings of Albuquerque’s historic (and some say haunted) KiMo Theater, watching the talented singer-songwriter Mary Gauthier close a fundraising concert I was emceeing. It was for the non-profit radio project I had co-founded in 2002, PEACE TALKS RADIO. Mary had followed Latina star Tish Hinojosa, and Native-American songster Bill Miller on the KiMo stage that night. All had volunteered their performances for the cause.

Mary had been applauded back on stage for an encore and chose to close the show with a new song of hers that she had yet to record. I was riveted from the first lines.

My father could use a little mercy now

The fruits of his labor fall and rot slowly on the ground

His work is almost over, it won’t be long, he won’t be around

I love my father, he could use some mercy now

(You can see a more recent performance of it here.)

Like probably everyone listening in that KiMo crowd, I was tossed suddenly into an introspective place of compassion for my own aging father. In 2004, both my mother and father were in their early 80s and, thankfully, in reasonably stable health. They were living in a retirement community in North Carolina. In fact, my father was still playing golf once or twice a week and was soon to be landing his first hole-in-one ever after 70 years of playing the game. (THAT was one great phone call I got to take!) My mother, never much for exercise, was active socially at the home and had become quite good at the new-at-the-time, no-sweat craze of computerized Wii-Bowling among the residents.

But despite their decent health status at that time, on my regular visits from Albuquerque to see them, I couldn’t avoid staring down the halls at the retirement complex that led to the assisted-living and hospital room units. There, “residents” turned into “patients”, moving ever more slowly in their last days, essentially waiting (some impatiently) to die. I imagined I would be standing vigil, relatively soon, at the bedside of both of my parents, watching them take their last breaths.

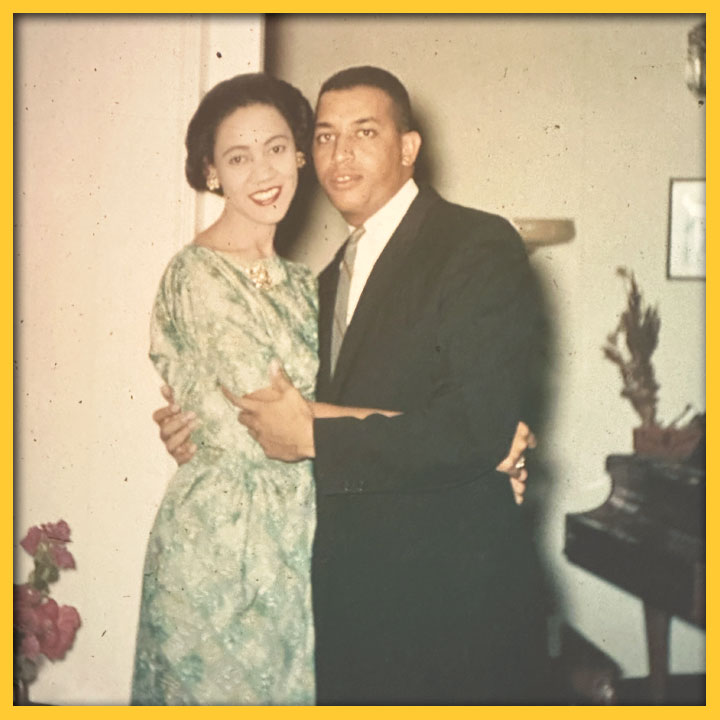

Flash forward not quite seven years from the benefit concert into the summer of 2011. My mom had been weakening through that year, but she was determined to make it to her 60th wedding anniversary party with my dad and the whole family gathering from near and far toward the end of July. She’d dressed up pretty for it, looked thin, but elegant and happy in all the pictures. A couple of days later, as I was about to leave for the airport myself to return to Albuquerque, I had them release the big 6-0 helium balloons from their party into the sky and made a video for the family.

Eight days later, my mother quickly contracted an infection and landed in the local hospital. I’d talked to her on the phone on my 55th birthday, Aug. 7, 2011. She seemed pretty spunky on the call, anxious to get home to their apartment. As she had many times before, it seemed that she would rebound from a health setback again. But the next night, I got the call from my older brother, John, who lived near them in South Carolina. He said she had taken a sudden turn to unresponsiveness. I wasn’t able even to book a plane from Albuquerque fast enough to get to her bedside, as she died a few hours after his call.

From that moment on, it was certainly my father who could use a little mercy now.

John, my younger sister Betsy, and I gathered in North Carolina to store or donate most of their apartment’s furniture to charity. My father, a World War II veteran of the Battle of the Bulge, retreated to the smallest assisted-living apartment in the complex. There was only room for the necessities – his bed, reading chair, desk, dresser, and television set. The Spartan surroundings suited his military training of needing just the basics to survive the battlefield march. The only luxury he insisted on was keeping his nice stereo equipment from the old apartment to listen to his cherished music collection from more than 70 years. He so loved the big bands, Dixieland jazz, and the best singers of the “American Songbook”.

By his 93rd birthday in December of 2015, he had to give up his beloved golf, and he’d retired from driving his car — just a bit before we three kids insisted on it. He’d watch the TV golf channel, listen to music, take slow walks around the grounds, and have meals with his small group of friends who made up his shrunken world. He had been diagnosed with slow-moving prostate cancer and mild Parkinson’s Disease. Thankfully he had no dementia, so he was still great to talk with. But physically he was basically outliving his parts’ warranties. He was also given to occasional fainting spells that, each time, sent him to the emergency room for evaluation and a night or two in that same small local hospital nearby where my mom had passed.

It was after one of these fainting spells that what we had dubbed ourselves as “Team Ingles” – my two sibs and I – and we mobilized to spend as much time as we collectively could with him. My brother and sister were both teachers with a little less scheduling flexibility than I (a freelance radio reporter and producer), so I came often and tried to stay long as I could. I’d have to fly back to New Mexico on occasion as I had recently added filmmaking to my suite of media projects. I was shooting and editing a short film that partially depicted the beginnings of our family’s efforts to offer my dad support in the lonely days after my mom’s death.

As his health challenges mounted for him in the months ahead, I couldn’t help but notice the profundity of every step in the process — his emotional struggle entering these final months of life, and my emotional struggle with bearing close-up witness to it. It was hard to watch his independence melt away.

I was getting my support, in equal parts from Susan, my partner of nearly three years, and my longtime behavioral therapist, who I’ll call “Don.” Don had helped steer me through a 2004 divorce of my own and a couple of bumpy attempts at relationships in the years before I met Susan. As I continued to get valuable advice from Don about how to better help my father, I began to make mental notes on possibly scripting the experience into a film that might help others deal better with the passing of an elderly parent or friend.

With each visit, it seemed that my dad was able to do less and less on his own. Even with a walker, he wasn’t steady enough to safely go on his treasured walks around the grounds, or even go to meet his friends at the retirement home’s cafeteria for meals. The hospital evaluation after his most recent faint uncovered even more heart weakness, and the mounting need for home health care and possibly hospice care was becoming inevitable. All this put each of us keeping him company in a challenging position. We’d at times be trying to divert his attention from the discouraging disempowerment from his declining physical abilities, while at the same time needing to dish out the “tough love” conversations about bringing on the extended care help that those declining abilities would necessitate.

My dad was resistant to accepting the extra help. Everything about his life seemed guided by the principle of self-sufficiency. He grew up in a career military family and went to military school. His father rose to two-star general status in the Army and was in charge of the essential Signal Corps in World War II. My dad was 1st Lt. Ingles in his active stint in his early 20s toward the end of the war in that crucial winter of the Battle of the Bulge in 1944 and ’45, earning the Bronze Star and a Purple Heart.

Unlike a lot of World War II veterans, who never spoke of their experiences on their return from war, my father finally crafted his experiences 40 years after the war by writing a detailed memoir in the 1980s. He wrote a fair amount about his sometimes-strained relationship with his father, whose stoicism around the crafting of the strategy of war was a quality my dad, slogging with enlisted men on the front lines, couldn’t adopt. My father wrote in his memoir, that he titled A Soldier’s Passage, that he could never be unemotional in combat. He felt the fear and dread too deeply.

That’s why my father didn’t make the military his own career and worked instead in management for 35 years with the phone company. His upper-level post there only magnified his devotion to responsibility. And while he handed that trait down to each of us kids in a mostly benevolent way as we grew up, he could also flash a sternness that reminded us who was the boss in this family. It was a sternness that could at times push out fear-tears from the rest of us, even my mom.

As I spent more time with my father in his last months, he’d make occasional references to his own father, which left me wondering if my dad was troubled over whether or not he really measured up in his own father’s eyes, or even in the grander scheme of things.

My dad was engaged in a deeply honest life review in these months. My therapy sessions with Don helped me make this time with my father rich and special. My memory of the advice he gave me at the end of one session just before I was headed back to the Carolinas for another visit showed up this way in the film drama I eventually scripted and produced. I borrowed the name of my dad’s memoir as its title: A Soldier’s Passage.

Don: When you’re with him, think about the harder stuff you’ve told me about in here over the years – between you and your dad.

Paul: What, that he blamed us kids for making my mom cry, when it was probably him making her cry? That he’s distant and remote from us sometimes. That he thought my politics was naïve and iill-conceived. That he didn’t always listen to me the way I wanted him to, like YOU do?

Don (smiling wryly): Right, stuff like that.

Paul (chuckles but shakes his head): Don, you know, he’s 93. I really don’t want to hit him up on stuff like that. He’s kind of earned his peace from me complaining about a few issues he left me with.

Don: No. Just keep that stuff in mind and listen to him. HE might have something to say about those things in these close-to-the-end times.

(WATCH: the scene from A SOLIDER’S PASSAGE)

It was good advice. The months that followed were emotionally hard on everyone but were often enriched by my dad volunteering his deepest feelings from his life review. Sometimes he’d confess troubling regrets like “I should have shown your mother more fun and been kinder to her,” or “I should have helped her more with you kids.” As Don had suggested, rather than try to rush in and say “There, there, THAT’S not true,” to try to make him feel better (especially if it was at least probably a little true), it was best to just listen, and let him talk himself out on it. Then, Don had told me, it was best to acknowledge his upset. Reflect back to him what he’d said, and even agree with him that it must be hard to feel that way, to make sure he knew that he’d been heard. THEN, it would better clear the way for me to suggest a different way to think about it.

For example, after reflecting back to my dad his regrets about his husbanding and parenting deficits, I gently suggested that he was only living up to the only model HE had, his own father, who was being a typical husband and father of the 1920s and 30s. Shared parenting and more equitable marriages weren’t happening back then and hadn’t advanced much in my dad’s era of the 1950s and 60s either. Pointing that out to him may have offered him some solace.

Other times, with only mild prompting, my father would unveil some story from his past that none of us had heard before. A lifelong baseball fan, I asked him when he went to his first major league game. It was 1932, he said, when he was 9 and the family was living in Washington, DC. With his own dad away at Officers Training School at the time, two African-American elevator operators in their apartment building offered to take him to a Memorial Day weekend game at Griffith Park. “They asked my mom if they could, and she said yes. She knew they’d take good care of me. I used to ride up and down in the elevator with them most days just talking to them. We saw the Yankees beat the Senators that day, and I’ve hated those Yankees ever since!”

There was much more of this over the ensuing months of his decline. As often as possible, I’d surreptitiously record his stories and late-life ruminations on my phone to share with the family later. They also wound up being the transcribed source material for my film.

Largely bed-ridden by the start of the summer of 2016 and dependent on 24/7 home health assistance in his apartment, my dad was growing impatient with his body’s failings and told me he wasn’t afraid of dying and “wanted to be with Audrey (his wife/our mom) again.”

As something of an agnostic myself, I told him, “Well, dad, wherever mom is right now, you’ll be going to the same place.”

My dad, never outwardly religious, responded to my somewhat open-ended statement with “I truly believe I will.”

On my commutes back and forth to see my dad, I’d been listening, often in tears, to one particular song from my own collection of music repeatedly. It was Bruce Springsteen’s “Land of Hope and Dreams.”

Grab your ticket and your suitcase

Thunder’s rolling down this track

Well, you don’t know where you’re going now

But you know you won’t be back

Well, darling if you’re weary

Lay your head upon my chest

We’ll take what we can carry

Yeah, and we’ll leave the rest

Well, big wheels roll through fields where sunlight streams

Meet me in a land of hope and dreams

(FULL LYRICS HERE) (PERFORMANCE HERE)

I’d even suggested to my dad that his impatience with getting to move on must feel like having his bags all packed and waiting on the platform at the station for a train. “You wait. You’re ready,” I said to him, “but you just don’t know when it’s scheduled to arrive.”

“Yes,” he said. “That’s a good way of putting it.”

My father drew his last breath at 5:23 in the afternoon of July 5, 2016, with my sister and I sitting on either side of his bed. My brother had been there earlier in the day too. We were softly playing some of my dad’s favorite music off my iPod. Close to the end, his favorite, Ella Fitzgerald, was singing near his ear “These Foolish Things Remind Me of You.” Its lyrics sounded almost like a playback of a Greatest Generation life.

The sigh of midnight trains in empty stations

Silk stockings thrown aside dance invitations

Oh, how the ghost of you clings!

These foolish things remind me of you

(FULL LYRICS HERE) (PERFORMANCE HERE)

Again, with the midnight train in an empty station, I remember thinking.

Weeks later in Albuquerque, I reviewed the whole experience with my therapist, Don.

“Seeing my father take his last breath was probably the most profound thing I’ve ever witnessed. I keep playing it over and over in my head. And you know what? I don’t think I WANT to forget it.”

“You never will,” Don said assuredly.

I’ve been treasuring every breath ever since.

Paul Ingles’ feature film adaptation about his father’s passing, A Soldier’s Passage, will screen at THE GUILD THEATRE in Albuquerque, Saturday, Nov. 11 (Veterans’ Day) at 12:30 pm.

SEE TRAILER TO A SOLDIER’S PASSAGE.

SEE FULL MOVIE A SOLDIER’S PASSAGE IN COLOR.

SEE FILM CLIP OF PAUL’S REAL DAD FROM THE CREDITS ROLL OF A SOLDIER’S PASSAGE.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

REFLECTIONS ON THE LOSS OF A NEW MEXICO CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER

By Carlyn N. Pinkins, M. A.

“The Dr. Harold Baileys of the world should inspire us all to do what we can to leave our communities, our towns and cities – our great state – better places than we found them. While we do our part to create the Dr. Harold Baileys of the future, we should also strive to make sure that the Dr. Harold Baileys of our past and present are never forgotten.”

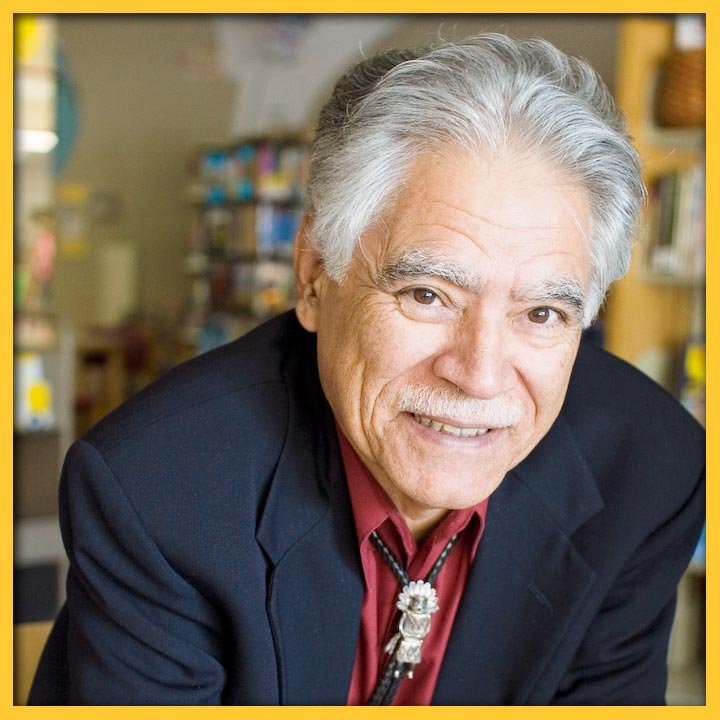

RUDOLFO ANAYA: CATCHING CULTURES IN BLESS ME, ULTIMA

By Richard Wayne Etulain

Anaya greatly expands the cultural contributions of his novel by combining the usual (Bildungsroman—growing up theme) with the unusual (complex, diverse New Mexico Hispanic culture)…

UP BY OUR BOOTSTRAPS; TWO LIVES IN RETROSPECT

By Finnie Coleman

I found myself fascinated with Dr. McIver’s transition from the stultifying hopelessness of the Segregation Era to the wistful hopefulness of the Civil Rights Era…

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

PAUL INGLES

Paul Ingles is an independent radio producer and occasional filmmaker whose career in radio, television, newspapers, and film dates back to 1975. After an 8 year stint as Production Director at KUNM at the University of New Mexico (1994-2002), his last 21 years have largely been spent doing freelance reporting and consulting for NPR, producing music history documentaries for public radio, as well as the talk series PEACE TALKS RADIO about peacemaking and nonviolent conflict resolution, and making 3 films. His film A SOLDIER'S PASSAGE was an official selection or award-winner at 18 film festivals around the globe. It will screen on Veterans Day, November 11, 2023 at Albuquerque's GUILD CINEMA at 12:30 pm.