IT'S THE MOST WONDERFUL TIME OF THE YEAR: THE BURNING OF ZOZOBRA AND HERALDING THE NEW SEASON

Now celebrating his 99th year, Zozobra is older than the Macy’s Thanksgiving Parade and the lighting of the Rockefeller Center Tree.

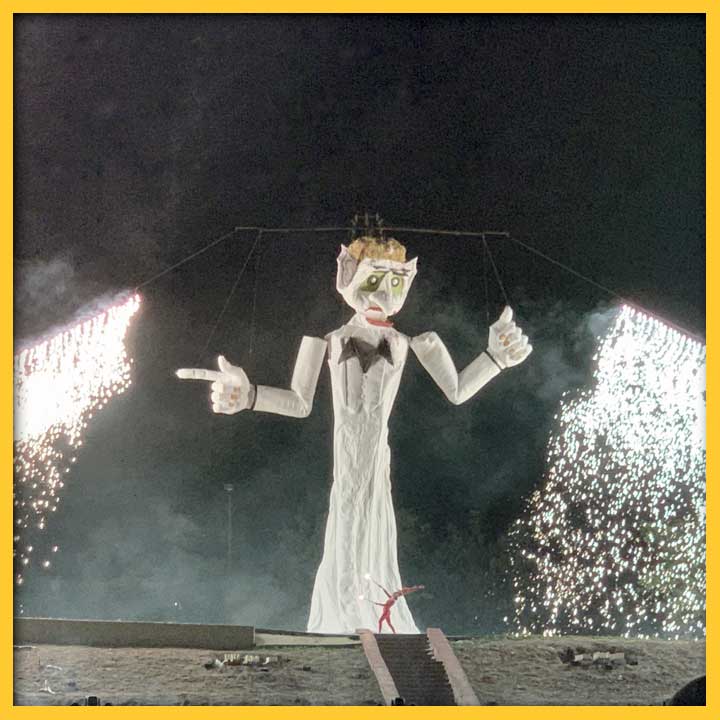

IMAGE: Zozobra and Fire Spirit, Helen Luna, flanked on either side by the traditional waterfall of fire. August 30, 2019. Photograph by Nicolasa Chávez.

SHARE:

The sweltering days of an extremely hot summer are finally cooling down. The sun sets slightly earlier each evening leaving a golden glow upon the land, and the first smells of green chile roasting fill the air. The last days of summer, the return of crisp mornings, and the welcome scents of autumn signal the coming of September and in Santa Fe, New Mexico, the new season is welcomed with a bang. As the final days of August near, the excitement and anticipation grow for the burning of Zozobra, a/k/a “Old Man Gloom.” A dazzling display of fireworks, lights, music, groans, shouts of “burn him”, and joy signal the beginning of “Holiday Season” for many a New Mexican. Now celebrating his 99th year, Zozobra is older than the Macy’s Thanksgiving Parade and the lighting of the Rockefeller Center Tree. He has always been associated with the end of the tourist season in Santa Fe, when locals once again find parking downtown or enter one of our favorite restaurants without an hour wait. He also signals the opening of Fiesta weekend in Santa Fe, culminating an entire season of events including live music, processions, parades and bailes. Fiestas exist throughout New Mexico and the southwestern United States, each city or town celebrating on its own special date. Santa Fe is unique in that it is the only celebration to include the burning of a giant effigy. Zozobra is a relative newcomer, appearing more than 200 years after the first proclamation of an annual Fiesta celebration.

Created by artist Will Schuster in 1924, Zozobra’s first appearance took place in a backyard party of the famed Los Cinco Pintores. Having traveled to Mexico, Schuster was inspired by the burning of effigies in local celebrations such as lighting Judas figures on Good Friday of Holy Week. In many cultures around the world, fire acts as a symbol of purification, rebirth, regeneration and renewal. The first burning of Zozobra coincided with Fiestas and took place in the autumn, a traditional time of year when old, or negative energy, is symbolically burned to make way for new, positive energy. The name Zozobra originated from a Spanish word meaning anxiety, or uneasiness. The first effigy was made of wood, wire and cloth, and was 6 feet tall. Shuster and friends wrote their worries, or gloom, on pieces of paper to be thrown into the fire and burned. Once the bad memories or worries were burned, dancing, music, and merriment ensued. From this tradition Zozobra is also referred to by the nickname in English “Old Man Gloom”.

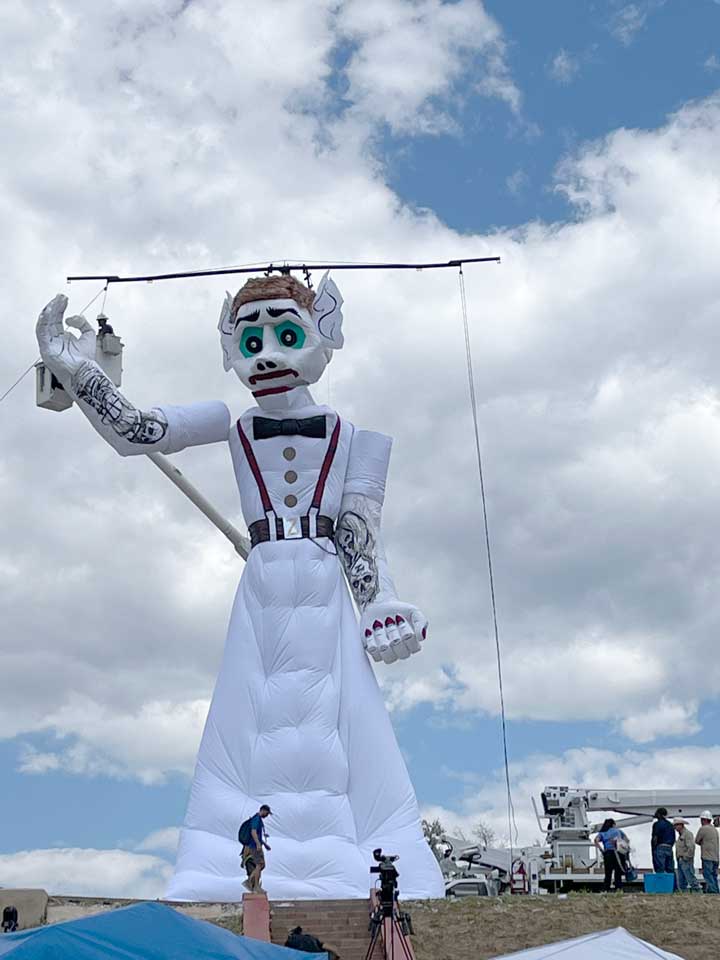

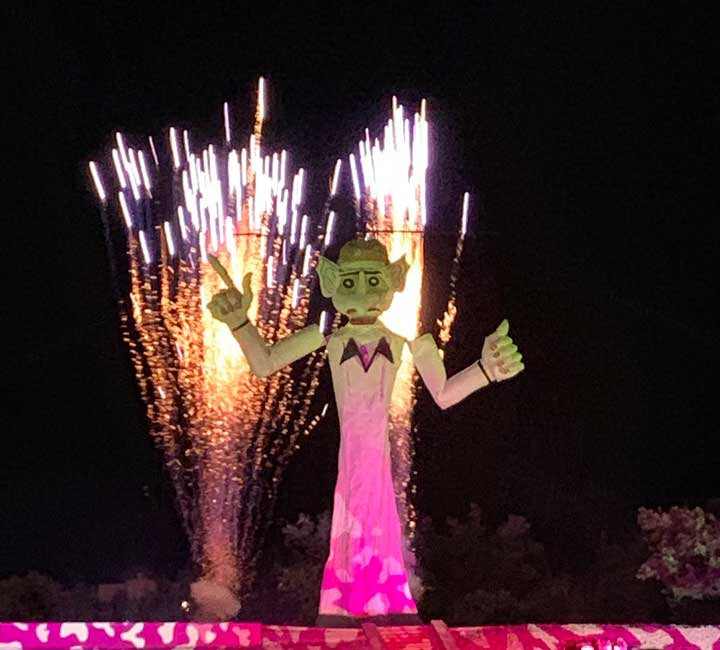

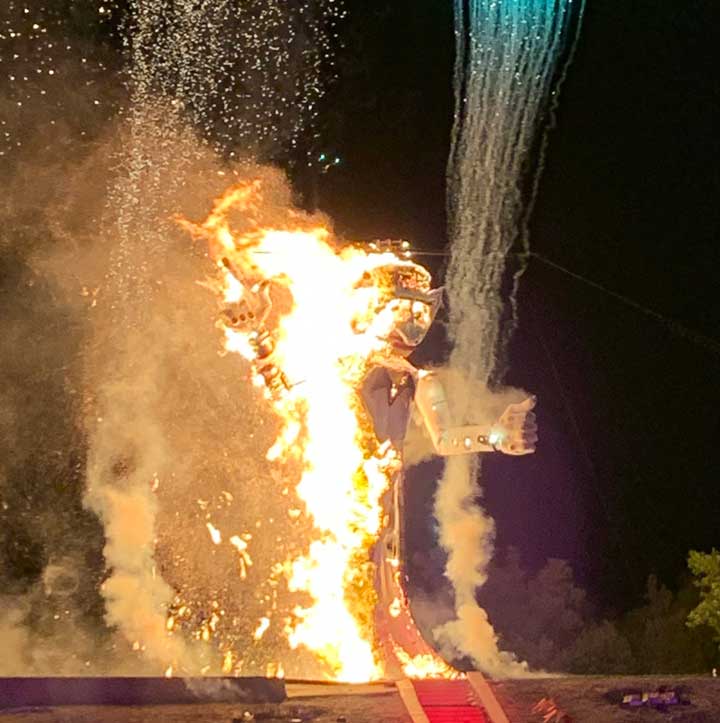

By the time of his first public burning on September 2, 1926, Zozobra had grown to 20 ft. in height. He continued to grow over the years to become the 50 ft. effigy we see today. What makes him unique, and fascinating is that he is not a still sculpture or solid statue, he moves and makes noise! Zozobra is one of the world’s largest marionettes. While his arms and head move and writhe, his loud groans and cries of anguish are conducted behind the scenes via a live voice and microphone. Every couple of years auditions are held for the voice of Zozobra. He is stuffed with hand-written notes of worry and gloom, along with the occasional divorce papers and parking tickets. The ceremony is not complete without a large group of school-aged children dressed in white sheets acting as glooms, they dance in front of him and precede the Fire Spirit, or fire dancer. The Fire Spirit was created by former New York City Ballet dancer Jacques Cartier, who was the first and longest-running performer. He danced before Zozobra, setting him ablaze for a steaming 37 years. Cartier’s student James Lilienthal took up the torch for another 30 years. Dressed entirely in red with a tall flowing headdress representing flames and carrying lit torches, it is the Fire Spirit who ultimately sets Zozobra aglow.

On June 19, 1964, Shuster transferred all rights, title, and interest in Zozobra to the Kiwanis Club of Santa Fe. The club has continued the annual tradition to the present day. Zozobra’s popularity has grown immensely over the years. The proliferation of online images, video, internet advertising and ticket sales have contributed to the growing participation in the event by locals and visitors near and far. During the 2020 Covid19 pandemic the public event was cancelled and instead viewers watched a live-stream burning. All over the country viewers were able to experience the annual tradition from their living rooms and many a Zoom party took place. I held my own with my children in Santa Fe and my best friend from high school who now lives in the Bay Area.

Now an entire lineup of events leads up to the big night. Throughout the summer there are various opportunities to help stuff the big man and gloom may be written on pieces of paper to include in the initial stuffing. An annual event called Zozo Fest takes place the weekend before the burning. Artwork, T-shirts, posters, mini effigies, are on display for public viewing amidst music and celebration. The main attraction is a preview of Old Man Gloom himself.

Still, one most “feels the burn” by experiencing the event live in the park. The annual celebration cleanses the soul and clears the mind. Whether ridding oneself of the past year’s baggage, or simply bidding farewell to a long hot summer, attending Zozobra is a celebration of joy. I try to attend the Burning of Zozobra every year, only missing a few here and there. When in attendance, I am filled with many past memories, like attending with my parents and sister as a young child, attending with college friends, bringing my own children, and thoroughly enjoying the event with my great aunt, who returned every year into her late 80s. Our family traditions always involved arriving at Ft. Marcy Park in the late afternoon and setting up a picnic full of tapas or charcuterie, fried chicken and watermelon, tortilla chips and green chile dip, a real New Mexican smorgasbord. We continue to visit and laugh all afternoon until sundown when the picnic blankets are packed away, and the first sounds of the eerie music herald the arrival of the Glooms. They receive cheers and shouts of encouragement from the crowd. The Fire Dancer arrives, creating a sense of suspense traveling up and down the steps. The crowd vigorously anticipates when the fire will touch down at the bottom of Zozobra’s robe, creating the blaze that warms us all inside and out.

Once Zozobra is burned, the final fireworks display provides a spectacular welcome to what many call the “official” holiday season. Some might argue the scent of green chile roasting in grocery store parking lots signals the arrival of the season. I believe it is both, for I love the scent in the air as I leave my parked car to head to the park to burn away any gloom from the past year. Zozobra energizes us for our seasonal leaf peeping, chile peeling, Halloween costume making, harvesting for Thanksgiving, well into the winter holiday season. We are cleansed and renewed and are warmed inside and out.

‘Tis the season to be jolly!

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

REFLECTIONS ON THE LOSS OF A NEW MEXICO CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER

By Carlyn N. Pinkins, M. A.

“The Dr. Harold Baileys of the world should inspire us all to do what we can to leave our communities, our towns and cities – our great state – better places than we found them. While we do our part to create the Dr. Harold Baileys of the future, we should also strive to make sure that the Dr. Harold Baileys of our past and present are never forgotten.”

RUDOLFO ANAYA: CATCHING CULTURES IN BLESS ME, ULTIMA

By Richard Wayne Etulain

Anaya greatly expands the cultural contributions of his novel by combining the usual (Bildungsroman—growing up theme) with the unusual (complex, diverse New Mexico Hispanic culture)…

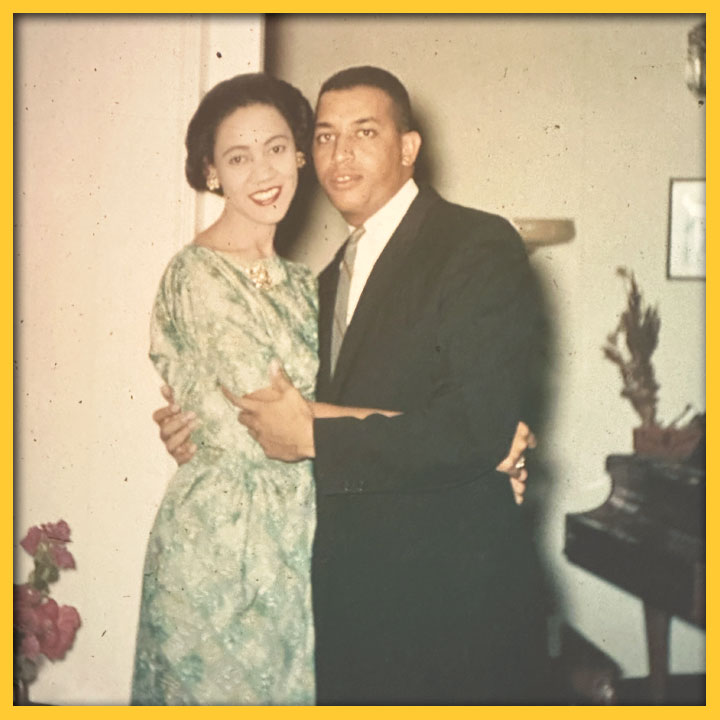

UP BY OUR BOOTSTRAPS; TWO LIVES IN RETROSPECT

By Finnie Coleman

I found myself fascinated with Dr. McIver’s transition from the stultifying hopelessness of the Segregation Era to the wistful hopefulness of the Civil Rights Era…

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

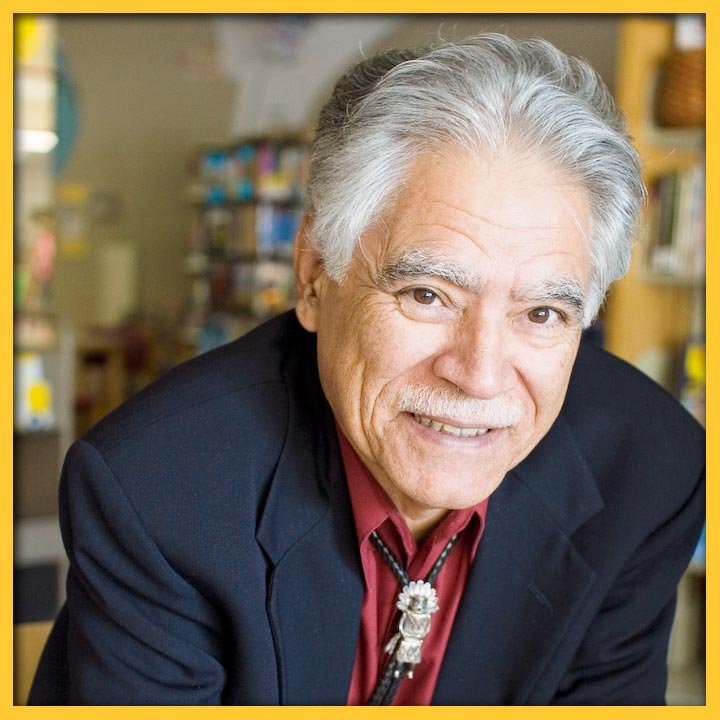

NICOLASA CHÁVEZ

Nicolasa Chávez, a fourteenth generation New Mexican, is a historian, curator and performance artist, whose work concentrates on the rich multicultural heritage of New Mexico and the connection between New Mexico and the Spanish speaking world. Her exhibitions include New World Cuisine: the Histories of Chocolate, Mate y Más, The Red that Colored the World, Flamenco: From Spain to New Mexico, and Música Buena: Hispano Folk Music of New Mexico. She was an invited guest curator at the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art in Kanazawa, Japan, for the exhibition Possibility of the Crafts: The Third Triennial of Kogei, which highlighted the traditional arts of New Mexico. She is a contributing author to the publication A Red Like No Other: How Cochineal Colored the World (Skira Rizzoli Press) and the author of The Spirit of Flamenco: From Spain to New Mexico (Museum of New Mexico Press) and A Century of Masters: the NEA National Heritage Fellows of New Mexico (LPD Press) which won a New Mexico Book Award. She performs and conducts lecture/demonstrations on the history of Flamenco, Spanish Dance, and Argentine Tango and currently serves as the Deputy State Historian for our great state of New Mexico.