SHARE:

Juneteenth is once again on the horizon.

It reminds of emancipation. It is characterized by celebration.

It is rooted in Black freedom delayed and so, therefore, denied. Our Black freedom is still delayed and still denied.

One hundred fifty-seven years after Union soldiers arrived in Galveston, Texas to inform still-enslaved Black men, women, and children of their liberty—which was not only signaled by Confederate General Lee’s surrender two months prior, but officially proclaimed by President Lincoln two and half years earlier—America reminds its Black men, women, and children that true liberty is hard-won, if it’s gained at all. If it’s gained in any full, democratic measure or with meaningful, systemic depth still remains to be seen.

Of course, this skepticism—this borderline cynicism—is validated not merely by every single attempt of the dominant culture to suppress, distress, and obsess over the mere notion of a free Black America since 1619, but by the devastating Buffalo, New York massacre in May. It is 2022. And it has been a long, fraught 403 years.

What does the emancipation celebrated by Black Americans on Juneteenth mean in light of the shattering violence ceaselessly perpetrated upon us? Revisited upon us simply for existing; simply for being the embodied reminders of America’s second deadly sin, African slavery, following its first, Native genocide. What does Juneteenth mean if Black Lives still don’t Matter, to the extent that an 18-year-old white man will drive more than 200 miles to prove that deadly point after two years incubating his anti-Black hatred in tireless scribbling and plotting and gun-modifying?

The yearly jubilee marking our past-delayed freedom is easily turned into a bittersweet anthem for our contemporaneously-denied freedom. Perhaps, like Black History Month, Juneteenth extols our plentiful gifts (“You’re welcome, America! For Angela Davis, jazz, W.E.B. DuBois, hip-hop, Michelle Alexander, Ryan Coogler, and a multitude of scientific and medical discoverers.”) as well as stoking advocacy for reversing the country’s curses (“For our trouble, here come reparations, socialized medicine, universal education, no profiling, and no redlining.”). Or is it not (merely) bittersweet, but a simple, painful, yet true evaluation that our Black-and-American celebrations must always be characterized by W.E.B. DuBois’s “double-consciousness”? The perennial acknowledgement that, out of our pain come our celebrations, much like our most transcendent artistic iterations—gospel music and the Blues.

These exercises of our aestheticism—the morally-reflective and -reflected exhibitions of our power and resilience as a people in art, education, and spirituality—are not made cumbersome by the weight of the dire truth. Black love and self-love, in fact, flourish when we are taught our history, learn about our heroes, embrace our struggles, and champion our victories. We then are steeped in our own human consequence, our necessity to this country, our aspiring ingenuity, and our profound compassion. All of this is why the application and discipline of history are so particularly targeted right now.

Because:

Black is beautiful.

Black is proud.

Black is bold.

Black is forever.

Also:

It’s terrifying being Black in America.

It’s strange being Black in America.

It’s powerful being Black in America.

You keep shooting, but you won’t kill Black America.

America is collapsing under the weight of its ahistorical pathology. It refuses to face the truth of the terrors of its past and the direct lineage to its terroristic present. In the clear light of day, our Black resistance has impelled the dominant culture to reverse its hagiographies and unlearn its mythologies. But we are now both emboldened: the rebellious disenfranchised versus the entitled overseers. The mainstreaming of American, sociopolitical, racial hatred did not abate or resolve it. And that is the challenge at hand; white supremacy’s exposure did not abash it.

While faced with the devastation of this most recent massacre, we’re reminded of like campaigns from the prior American Nadir. In years’ past, whether African Americans played by whites’ own capitalist rules in Colfax (1873), Wilmington (1898), Atlanta (1906), or Elaine (1919), or flourished even under the duress of American apartheid in Tulsa (1921) or Rosewood (1923), America was then, like now, unwilling and unable to allow for our growth and success. It got to the point where three generations after Reconstruction, and only a single generation after the close of the Civil Rights Era proper, the Reagan era convincingly stereotyped the least of our brothers and sisters as indolent, thankless, and savage.

But this is why we are so amazing: because, what had actually happened was, that from the literal depths of America’s sociopolitical perdition, we built this country. We turned it into a global powerhouse 200 hundred years ago. For free! And we bolstered that worldly position in peacetime and in every war the United States pulled us into ever since. Like the prophet James Baldwin reminds us, we have “the great advantage of having never believed the collection of myths to which white Americans cling.” Instead, we honor the sacrifices our ancestors made so that we can carry their torch of liberty and hope through these dark hours, out of this second American Nadir, forging a third Reconstruction, and building a Beloved Community.

The lengths to which our enemies go may stoke our fear but cannot shake our righteousness.

We’ve heard tell of those early Juneteenth celebrations, rife with lively song and resplendent, colorful outfits.

It’s a superpower, is it not? To be able to come together, whatever the circumstances, denied or delayed? However sour the reminder, however sorrowful the circumstance, yet still finding meaning and succor in our actual and fictive kinship, and our shared history. We’ve become familiar with coming together compassionately in a country hell-bent on dividing and conquering us at all cost. Our outrage reminds us of our moral high ground. Our stories, our music, our lived experience spur us to stay angry and protective and proactive, and also invite us to laugh and cry and console as well.

We have our collective voice to say what others won’t; to speak truth to power. We have a truth-telling obligation; we speak and sing and create our art and record our history on the shoulders of our amazing forebears. And we can relish that responsibility. The up-and-coming generations are even more attuned to the needs of our well-being, holistically—body, mind, and spirit. We can be grateful for the empathetic behaviors they’re more practiced in than any prior cohort of young Americans. It’s that much more light to shine on the oppressors’ dark corners and platforms.

Of course Black Lives Matter. Of course Juneteenth carries, within its very origin, the duality of being Black and American. We celebrate June 19 in spite of American white supremacy. And, as a mentor shared with me, we learn from our ancestors and the Juneteenth story and live out the good we learned from it. That was our commission then, and it’s our commission today.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

NEW MEXICO’S AMAZING BLACK HISTORY

By Rob Martinez, State Historian of New Mexico.

“African history runs deep in New Mexico. Black history is often framed within the institution of slavery, but in New Mexico, New Mexicans of African descent were ambassadors, explorers, colonists, soldiers, cowboys, discoverers, settlers, businessmen, educators, and much more.”

SCANNING FOR STORIES

It was a Friday afternoon in November and I was driving on a state road through the hills of the Mimbres Valley. The entire landscape was bathed in a golden hue because the tree leaves had made their full conversion to a bright yellow color just before falling off the branches.

REFLECTIONS ON THE LOSS OF A NEW MEXICO CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER

By Carlyn N. Pinkins, M. A.

“The Dr. Harold Baileys of the world should inspire us all to do what we can to leave our communities, our towns and cities – our great state – better places than we found them. While we do our part to create the Dr. Harold Baileys of the future, we should also strive to make sure that the Dr. Harold Baileys of our past and present are never forgotten.”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

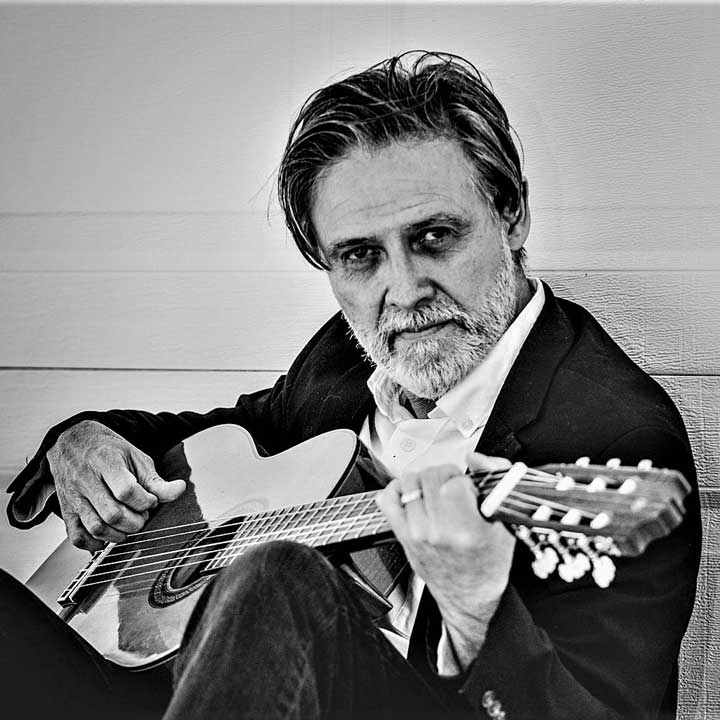

SEAN CARDINALLI

Sean Cardinalli is a writer / producer / activist with over 20 years’ experience in film / TV development and production and over a decade’s experience speaking and writing about social justice, addiction, and well-being. Under his development banner, Alterity, Sean has built a slate of IP focused on broader BIPOC narratives to produce, collaborating with a diverse cohort of creatives and executives. Contracted by the New Mexico Black Leadership Council, Sean coordinates initiatives which cultivate progressive partnerships and build community communications infrastructure. He holds a BA in English literature from UC Berkeley and is the proud father of two amazing teens.