SPACESHIPS, RAY GUNS AND LIFE LESSONS

“science fiction allows you to discuss difficult and fraught topics in what is a safe space and at arm’s length.”

PHOTO CAPTION: Publicity photo of Leonard Nimoy and William Shatner as Mr. Spock and Captain Kirk from the television program Star Trek. Jan. 12, 1968, NBC Television. WikiCommons.

SHARE:

For decades science fiction was the ugly stepchild of literature. Critics sniffed and dismissed the genre as “kids’ stuff”, ray guns, spaceships and manly men (always white) with square jaws and boundless knowledge which they were eager to impart to the breathless female who had just been rescued from the clutches of evil aliens.

But that wasn’t science fiction. It never was. Men like Jack Williamson were exploring the dangers of A.I. and robotics decades before it became a reality in his novelette With Folded Hands in 1947. Isaac Asimov was exploring the inevitability of the fall of empires in his Foundation novels published in the early 1950s as well as postulating the Three Laws of Robotics in his robot novels. After Dolly the Sheep was cloned my mother-in-law called me, very concerned about this and asking what I thought. My response was, “What took so long?” because science fiction authors had been writing about the effects and the morality of cloning for decades before the technology caught up to writers’ imaginations.

Today the prose world of science fiction embraces writers from a myriad of different cultures, creeds, races, genders and sexual identities, and what publishers discovered was that science fiction will always sell. It might not be a top seller like romance and mysteries, but its readers are devoted because, despite numerous dystopian books over the decades, science fiction is at its heart, hopeful. It looks to the future and to the stars.

Is that fascination with the heavens coded in our DNA? As Carl Sagan once said, “We are made of star stuff.” What did he mean by that? Well, atoms form molecules and molecules in sufficient numbers combine into substances that form the matter from which everything is created — including us.

Eventually, technology moved these dreams of distant worlds off the printed page and onto television and movies screens. In 1966 the Starship Enterprise sailed across our television screens. Star Trek had arrived. In the depths of the Cold War, we were presented with a diverse crew that included a Russian, a Japanese helmsman, a black woman communication officer and an enigmatic half-alien/half-human from a mixed marriage trying to navigate between two cultures.

During its three seasons on the air the original Star Trek brought to the screen the first interracial kiss, which led to the episode being banned in the South — as well as an exploration of the dangers of proxy wars, the catastrophe of overpopulation and the evils of racism. Star Trek from the very beginning was Woke as hell.

That exploration of deep and weighty issues has continued with new versions where episodes explored the rights of androids, the complexities of civil war and terrorism, the dangers of religious wars. Trek remains true to its founding principles and is still Woke as hell.

For those of us who loved science fiction from childhood, who endured the slings and arrows of being dubbed and mocked as a geek or a nerd … well, we’ve had the last laugh. The geeks have inherited the Earth. Modern entertainment from movies to games to television series are dominated by science fiction and fantasy.

So how is this kids’ stuff relevant to the humanities? At present the world and this nation are deeply polarized, and we all feel as if we are communicating across a vast cultural, religious, political and social divide. Bring up racism or trans rights, or police brutality, climate change, the efficacy of vaccines and you are going to meet strong resistance if not outright blowback when you try to discuss these issues.

But science fiction allows you to discuss difficult and fraught topics in what is a safe space and at arm’s length. No one will feel like they are being confronted when you are discussing alien rights, or android rights, racism, misogyny, imperialism, a world ravaged by climate change or a repressive fascist regime, if those discussions are taking place in a distant future, or on another planet, or in a fantasy world.

When people are immersed in a rollicking good story they are being swept along, but later the issues raised in those stories can be analyzed in quiet and personal contemplation. And perhaps minds will be changed and hearts opened. It is easier to examine the mote or the beam in our own eye if we are seeing it through the lens of aliens on a distant planet or elves or dwarves or orcs and dragons in a fantasy world. Perhaps by reading that story a person can begin to question their own biases and assumptions.

I’ll end this with this quote that I love about the power of words. The ancient Greek lyric poet Pindar, wrote “Words have a longer life than deeds.” But words can power deeds, so let’s just try to make sure those words and the subsequent deeds bend the moral arc of the universe toward justice and not toward evil.

PASA POR AQUÍ

ADDITIONAL BLOG ARTICLES

NEW MEXICO’S AMAZING BLACK HISTORY

By Rob Martinez, State Historian of New Mexico.

“African history runs deep in New Mexico. Black history is often framed within the institution of slavery, but in New Mexico, New Mexicans of African descent were ambassadors, explorers, colonists, soldiers, cowboys, discoverers, settlers, businessmen, educators, and much more.”

SCANNING FOR STORIES

It was a Friday afternoon in November and I was driving on a state road through the hills of the Mimbres Valley. The entire landscape was bathed in a golden hue because the tree leaves had made their full conversion to a bright yellow color just before falling off the branches.

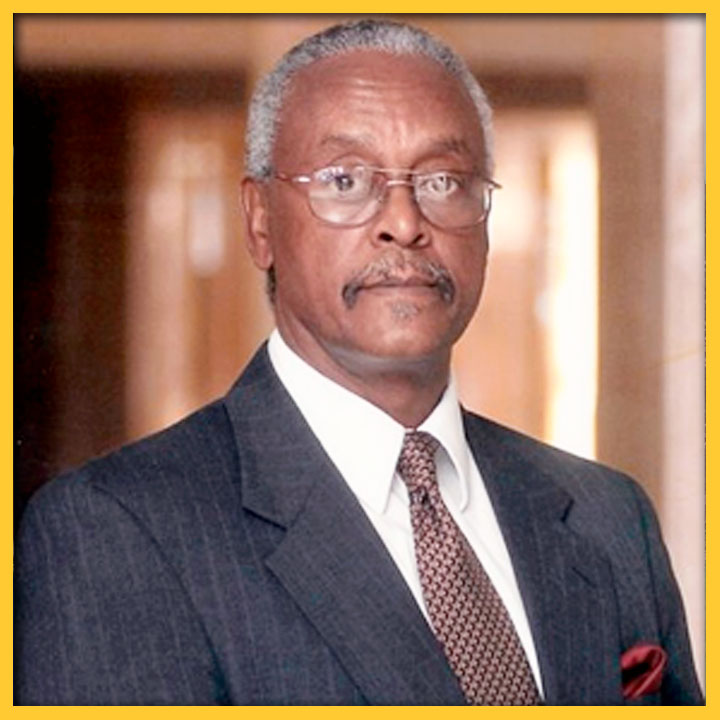

REFLECTIONS ON THE LOSS OF A NEW MEXICO CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER

By Carlyn N. Pinkins, M. A.

“The Dr. Harold Baileys of the world should inspire us all to do what we can to leave our communities, our towns and cities – our great state – better places than we found them. While we do our part to create the Dr. Harold Baileys of the future, we should also strive to make sure that the Dr. Harold Baileys of our past and present are never forgotten.”

SHARE:

DISCLAIMER:

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this blog post/article does not necessarily represent those of the New Mexico Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

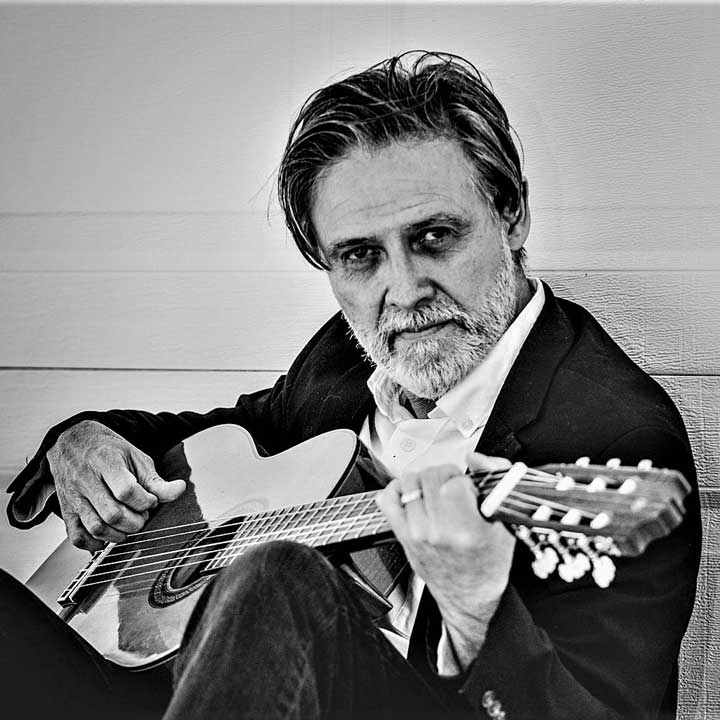

MELINDA SNODGRASS

Melinda M. Snodgrass studied opera at the Conservatory of Vienna, graduated Magna cum Laude from U.N.M. with a degree in history, and went on to Law School. After 3 years as a lawyer, she realized she hated being a lawyer and turned to writing.

In 1988 she accepted a job on Star Trek: The Next Generation and began her Hollywood career where she has worked on staff on numerous shows and has written television pilots and feature films. She currently has two television series in active development.

In the prose world she writes for and co-edits the shared world anthology series Wild Cards with George R. R. Martin.

In addition, she writes her own novels. She is working on a new fantasy novel, and her space opera, Imperials is available, and her Carolingian series has been completed and will soon go live.

For fun she rides her dressage horses and plays role playing and video games.